Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.

– George Santayana

Archives provide physical evidence to support stories of the past and they extend the memory of a society.

“Without archives, we’d only have the stories of the winners in history, we wouldn’t know what ordinary people were feeling, thinking and doing,” Joanna Bourke, professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London, said on the importance of archives.

Rarely is Rwanda’s story told today without the mention of the 1994 massacres that saw 800,000 people killed. In 2003, the Rwandan government’s National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide and British-based Aegis Trust started a project that culminated in The Genocide Archive of Rwanda. This archive opened in 2010, giving the general public access to documents, photographs, artefacts and videos from the horrors of 1994 in Rwanda.

It is meant to preserve the memory of that piece of Rwandan history and to provide information that will help prevent another such genocide. To this end, some of these records are digitized and available online, allowing access to more users and further preserving them.

Nigeria’s national archives are in dire need of a similar intervention.

National Archives of Nigeria, a department of the Federal Ministry of Information and Communications, is housed in Enugu, Ibadan and Kaduna. The department was established in 1954 as the Nigerian Record Office until 1957 when legislation changed its name to the present one.

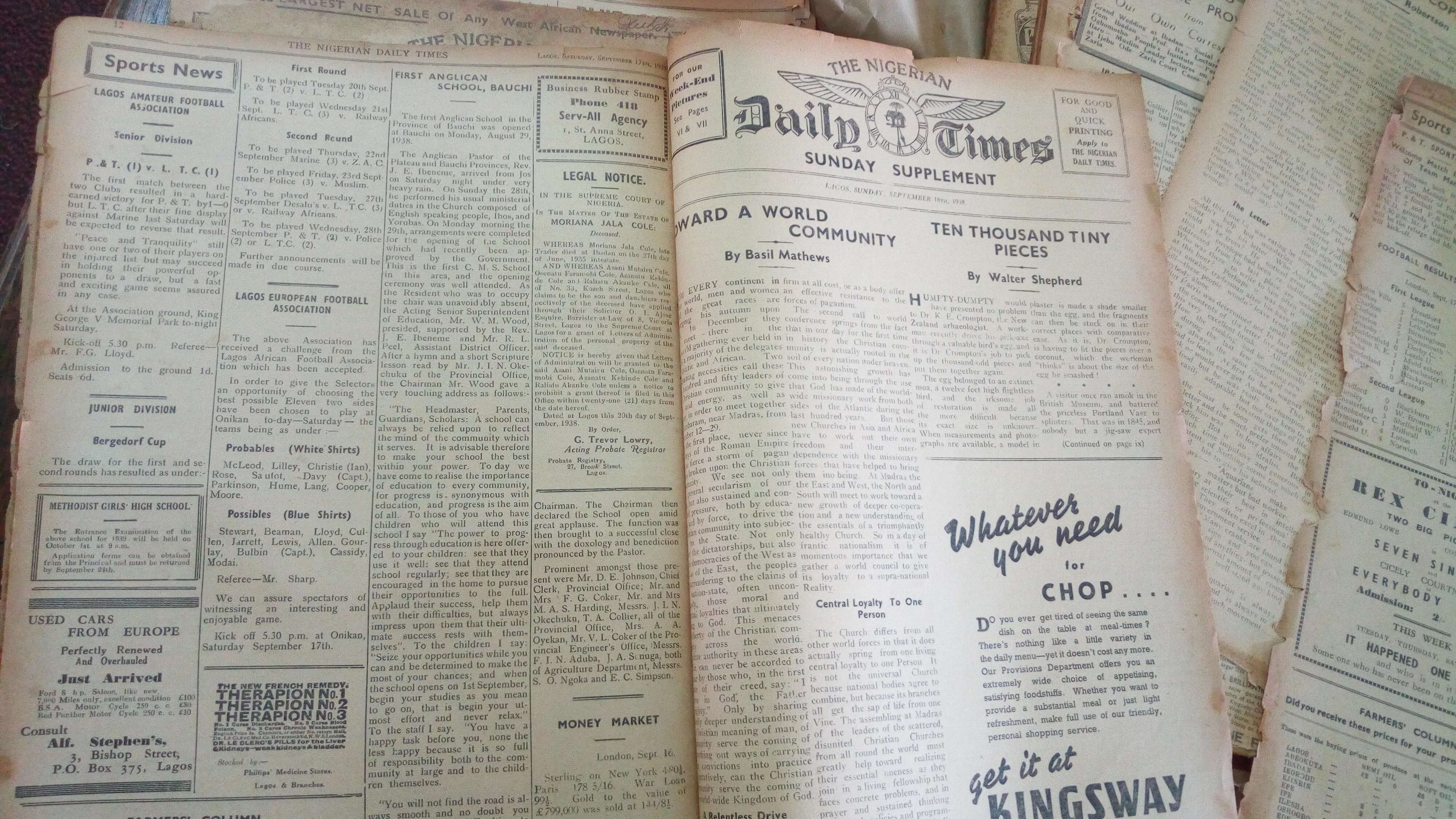

The archives hold records, documents and artefacts that date back to pre-colonial times.

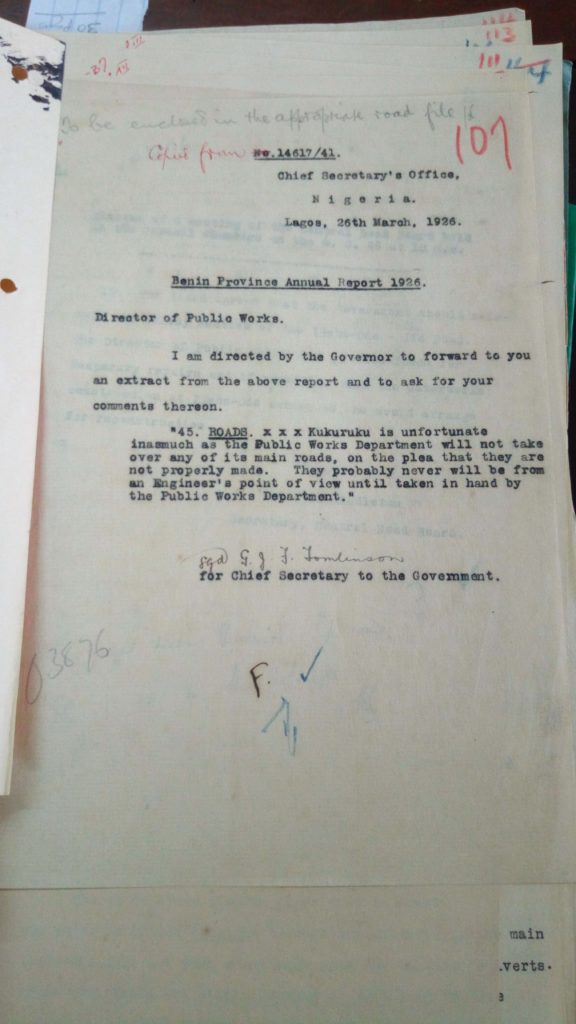

Kaduna, for instance, holds Arabic manuscripts written by Uthman dan Fodio, the founder of the Sokoto caliphate. While records of colonial administration that date back to the 19th century are also available at Ibadan and Enugu.

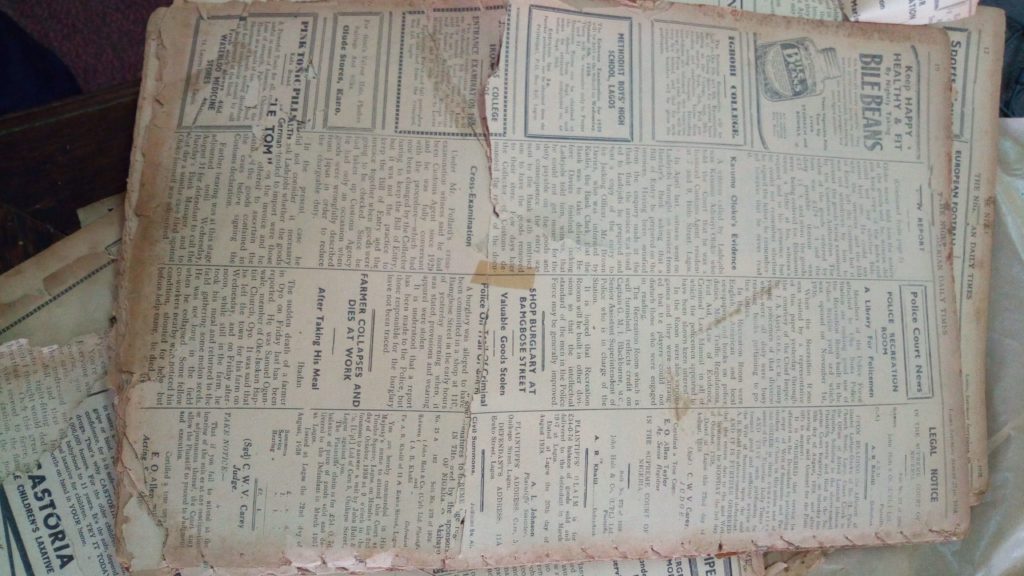

As Dr Mohammed Salau, a history professor at the University of Mississippi, notes (of the Arabic manuscripts in the Kaduna archive), “most of the materials are in a bad state due partly to wear and tear of repeated use/deterioration.”

The situation is similar at the Ibadan office, which I visited a couple of times last month. Some of the documents have become delicate and crumbled as I turned the pages.

A senior official with the National Archives of Nigeria who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity said: “My heart bleeds as an archivist when I see the deterioration of these archive materials.

“Some are brittle and disintegrating before our eyes, and there’s not much we can do due to lack of funds,” this official explained, that funding from the federal government is very limited, and acknowledged that digitization would be a very effective way of preserving some of the endangered materials.

They also pointed out that physical infrastructure needs improvement.

“Our cooling units don’t work,” they complained, “most of the materials are not being kept under the right temperature to preserve them.”

“I remember that some years ago, there were efforts to scan and digitize the archives, but at some point the machine being used broke down and that was the end of the process,” the anonymous official said, “and I do not know the whereabouts of the digital copies created at the time.”

They added that the establishment has had promises of funding support from influential members of the society who at one point or the other approach the archives for help while trying to locate some dated information, “but after they get what they need, we do not hear from them again.”

According to the official, because the national archive needs to maintain a degree of sovereignty over the records they manage, they have turned down certain foreign institutions interested in assisting with digitisation.

“We have also had offers to help us with digitization from international organisations, like the British Library, but we have had to turn them down because we are wary of the requests that digital copies of the entire archives or a substantial part should reside in their own domain,” they revealed, naming Oracle and Wikipedia as well.

“It is not proper for these organisations to have such control over our national archives. If they truly want to help us, they shouldn’t request copies,” implying that such offers are not entirely altruistic.

Responding to a question on the purported offer by the British Library, Dr Marion Wallace, Lead Curator, Africa at the British Library, told TechCabal via email: “I guess it may concern the Endangered Archives Programme, run by the British Library, which gives grants to projects to preserve archival and manuscript heritage, mainly through digitisation.”

“Projects are initiated by the applicants in the relevant country, or by experts, usually academics, from another country. The British Library doesn’t, therefore, approach individual institutions proposing to digitise their holdings.”

Wallace further clarified that: “I did have the privilege of visiting the National Archives in Ibadan in 2017, along with several other archival/library institutions in Nigeria, and I would certainly have given them information about EAP in case they were interested in applying for a grant.”

Some of the materials in Nigeria’s national archives have benefitted from EAP’s grants for digitisation, despite the archives’ seeming reluctance to allow copies to live outside of their domain.

Salau was awarded a £9,700 grant by the EAP to digitise some pre and early colonial records, about 2,376 items, at the Kaduna site of the National Archives of Nigeria. Digital copies of these records, tagged EAP535, are now available via the programme’s website, in accordance with the grant’s open access policy that requires the material to be available on the internet for free.

The anonymous source stated that they did not know of any such project. But they agreed that urgent steps need to be taken to commence digitization.

Wallace also informed of a recent unsuccessful application to digitise some of the documents in the care of the national archives. “We have identified one unsuccessful application to the Endangered Archives Programme in 2017/18 which involved material in the National Archives of Nigeria. The applicants were external to the National Archives,” she explained, but that the National Archives “would have been the archival partner had the application been successful.”

Ultimately, without urgent intervention, regardless of the source, collective memories of Nigerian society that live in the national archives face certain extinction.