It’s 6:30 AM in Lagos or Port Harcourt. You have only 30 minutes to start your commute to work but you still want to eat breakfast. You decide to make a sandwich but you need to buy bread. You head to the kiosk down the street. A woman in her mid-40s peers out from behind a window, surrounded by boxes of biscuits, minerals, and sweets. She passes you the loaf of bread, and you slip her 200 Naira.

Over the years, local and multinational retail chains from Shoprite to Prince Ebeano have emerged in Nigeria. However, they cater to only a small sliver of the population. In Lagos, Shoprite is more of a destination where people explore merchandise and snap pictures than shop.

Rather, 98% of Nigerians shop in the informal retail sector, just like our fictional woman retailer who sold you your bread. Informal retail encompasses a host of outlets that range in size: tabletops, kiosks (managed by mallams), retail stores, mini-marts, and supermarkets. This doesn’t even account for the direct-to-consumer (DTC) channels of hawkers who are, in reality, an extension of informal shops. They often buy goods on credit from retailers and ply a brisk trade of certain items that do well in Lagos traffic: Gala, meat pies, water sachet, minerals, and in Lagos, agege bread. Over 60% of the squishy bread is sold in traffic. [Yet, in Port Harcourt, the taste is more varied with over sixty types of bread available in the market.]

Retail in Africa

Informal retail is dominant across sub-Saharan Africa. Its size and scale are immense: it contributes $2.6 trillion to the region’s nominal GDP, drives $1 trillion in annual sales, and provides 80% of jobs. Informal retailers sell 80% of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) to African households. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), 90% of retail transactions in Africa happen through informal channels. These informal transactions account for 70% of retail transactions in Kenya, 96% in Ghana, and 98% in Nigeria and Cameroon.

Informal retailers like street kiosks, tabletops, and hawkers are the de facto Shoprites, Walmarts, and Carrefours across Africa due to their proximity to consumers. In Africa, it’s easier to go down the street multiple times a day than take a bike or Uber to a supermarket to pick up only one item. In Nigeria, the average retail shop is located within a 500 MT radius of 100 households. Embedded in neighborhoods, informal retailers are key institutions in communities. They know their customers incredibly well. And it’s not just what they’re eating. They hear the neighborhood gossip, about who is getting married, divorced, or whose child got expelled from school. As part of the fabric of local communities, they have customers’ trust, which is priceless.

Broken supply chains

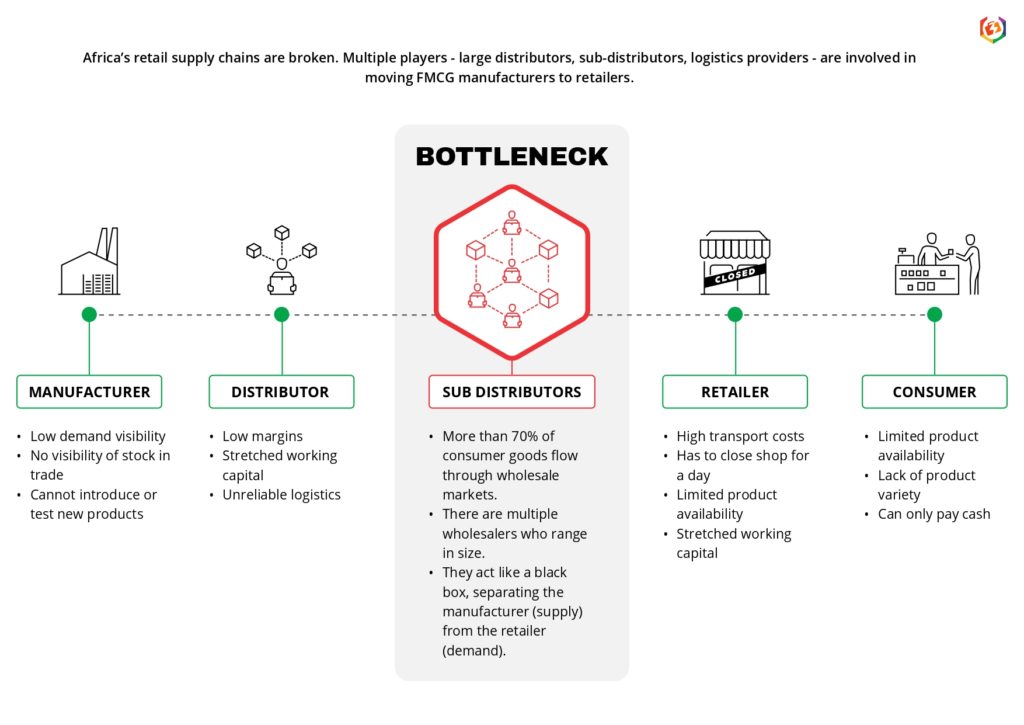

Despite informal retail’s importance in driving commerce and economic activity, it is uncoordinated, fragmented, and unstructured. Multiple players exist in retail supply chains – manufacturers, distributors, sub-distributors, logistics providers, and retailers – but they operate in silos. Supply is disconnected from demand.

The breakdown in supply chains results from the difficulty in reaching retailers, and ultimately, customers. Distribution networks – making sure your product is within easy reach of customers – are costly to build. They require warehouses, logistics fleets, and staff.

In Nigeria, proximity to the customer is everything. With their deep pockets, large manufacturers have built their own distribution channels to reach retailers. Multinational FMCG companies, like Coca-Cola, Seven-Up, Unilever, and Nestle, have invested heavily in their own distributor networks. They supply inventory on credit and lease fleets. Yet, given the great expense of direct distribution, even the FMCG giants only sell 30% of their goods via their own networks; the remaining 70% is sold via sub-distributors.

This is where informal retail enters a black box. Wholesalers, which cluster in feeder markets like Balogun in Lagos or Mile 1 market in Port Harcourt, separate supply from demand. There are no direct links between FMCG manufacturers and the end buyers (the retailers).

This leads to a host of problems. Unable to directly access retailers, manufacturers are in the dark when it comes to market trends and product performance. They lack visibility on demand and stock in trade. Lacking market research, they can’t introduce new products or do promotions. Manufacturers can’t use discounts to drive sales for a particular product as the wholesaler is likely to eat the margin.

Large distributors also lose in fragmented supply chains. They struggle to reach retailers and don’t know about product performance – are customers buying more Indomie and less spaghetti in a certain area? Should they cut back or increase the supply of Dettol soap? This limits their turnover of inventory to strain their already stretched working capital. They can’t count on reliable logistics, either.

Yet, the retailer bears the brunt of the disjointed supply chain. Retailers – the vast majority of whom are women – have to travel to the wholesale market to stock up on their Indomie, minerals, soap, and other staples that make up their 100 SKU inventory. Not only do they incur the cost of transport, but they also have to close shop for the day and lose business. The problems don’t end there. Retailers travel all the way to Lagos Island or Oil Mill market, only to discover that wholesalers have run out of some key items. After a costly trip to purchase quantities of 10 items, a retailer might return with a stock of 5 or 6 items.

Technology is transforming informal retail

As the world is increasingly coming online, technology is solving deeply entrenched problems. Informal retail isn’t an exception. Founded in 2020 by Deepankar Rustagi, Omnibiz is a B2B e-commerce platform digitizing and modernizing the informal retail supply chain.

Omnibiz collaborates with everyone from manufacturers, distributors, logistics providers, and retailers) to help them to grow their businesses. The company gives visibility on supply and demand through its software solutions tailored to each supply chain player. This collaborative approach allows Omnibiz to focus on solving the problems of retailers.

Deep Nigerian FMCG expertise

A veteran of the FMCG and technology sectors, Rustagi has lived in Nigeria for over two decades. He started his career out at Tolaram, maker of the leading instant noodle brand, Indomie. Tolaram has truly hacked distribution in Nigeria – Indomie is found in the most isolated corners of the country. His three years at Tolaram were a masterclass on last-mile delivery. After leaving Tolaram, in 2011, Rustagi launched VConnect. An online business directory, VConnect was ahead of its time and predated the entry of Google and the launch of its small business index.

VConnect brought 800,000 Nigerian SMEs online and connected them to customers. But, given the lack of online payments, a viable business model proved elusive. By 2017, Rustagi shut down VConnect and started consulting for FMCGs.

As a consultant, Rustagi had a front-row seat to the problems besetting FMCG manufacturers. He observed that manufacturers were all reinventing the wheel – they used ineffective siloed methods to reach retailers. To solve this problem, Rustagi launched Mplify in 2019. An ERP system, Mplify helped manufacturers manage inventory and distribution. Used by 200,000+ companies, Mplify was a success but Rustagi would soon pivot the business yet again.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic hit. When Nigeria went into lockdown for two months, retailers were stranded. They couldn’t travel to the market to buy goods.

This unprecedented crisis was a light-bulb moment. How do you plug a broken supply system? You start from the bottom up. Instead of focusing on the first players on the chain, the manufacturers, Rustagi decided to dedicate his energy towards the end of the chain—retailers.

Starting from the bottom up

Trusted by customers, retailers should be the core focus of any B2B e-commerce solution. Omnibiz turned its attention to the retailer and deliberately chose to collaborate with manufacturers, distributors, and logistics providers to solve their problems in the supply chain, too. Rustagi and the Omnibiz leadership reasoned that if they created incentives and made onboarding onto the platform a winning proposition for all players, they could use partners’ infrastructure (warehouses, delivery vans, and staff) and save precious capital to solve the problems of retailers.

Omnibiz’s business model is based on three core principles:

- Collaboration not disruption: Omnibiz does not aim to disrupt but collaborate with existing players. Omnibiz helps everyone in the supply chain—manufacturers, distributors, logistics providers, and retailers—to trade smarter and more profitably by connecting consumer goods supply with demand. Using the Omnibiz platform, manufacturers can adjust order volumes to demand and increase inventory turnover as well as launch promotions and test new products. Distributors can accelerate their inventory rotation and save on working capital as they increase their access to retailers. Lastly, logistics providers can dramatically increase their deliveries.

- A laser focus on retailers: Omnibiz is devoted to helping retailers scale their business. Retailers can order through the e-commerce store and receive goods delivered to their shops, sparing them from visiting the markets. After solving the inventory problem, Omnibiz introduced a buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) service so retailers can increase their purchases.

- Staying asset-light: An asset-light model is crucial to Omnibiz. It owns no warehouses, delivery vehicles, and houses only a small batch of inventory. To remain asset-light, Omnibiz partners with distributors who operate warehouses and also third-party logistics providers who run their own fleet of delivery vans and bikes. As a result, Omnibiz can deploy capital to solve the problems of retailers.

This model allows Omnibiz to stay true to its collaboration principle – it helps all players to expand their reach rather than replace them.

The vision for retail in Africa

Although supermarkets have emerged across sub-Saharan Africa, the future of retail on the continent lies in shops and kiosks. Shoprite and Carrefour won’t replace neighborhood retailers, who are trusted by customers. Rather, technology will modernize informal retail by fixing stockouts, eliminating counterfeit goods, and providing retailers with access to credit. Omnibiz believes that the informal retailer, empowered by technology, is the face of African modern retail.

About Omnibiz

Omnibiz is an e-commerce platform serving Nigeria’s informal retail sector.

It is a digital supply chain where retailers can buy needed goods directly from and also communicate with distributors. Omnibiz’s system runs through a mobile app, Whatsapp channel, and phone number. The startup received $3 million in a funding round led by V&R Africa, Timon Capital, and Tangerine Insurance in 2021 to expand into new markets.