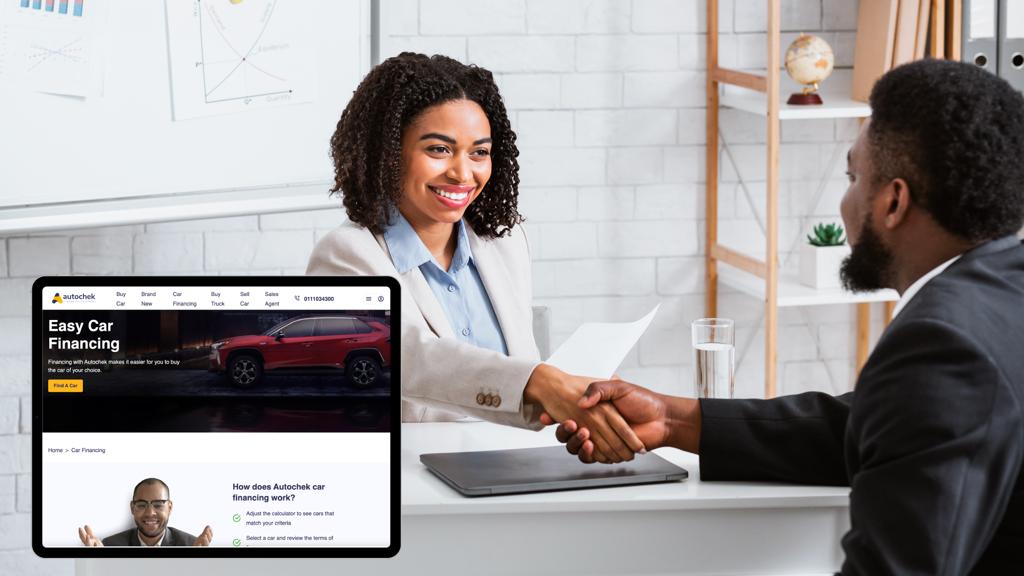

When Eden Life, a Nigerian home concierge startup, announced its expansion into Kenya last week, many questioned the move, curious as to why the company didn’t expand into another Nigerian state before going international.

But Eden Life, which provides services like cleaning, laundry, and meal delivery to busy professionals, seems to have a bigger plan in mind. By acquiring Lynk, a similar company that connected informal workers to job opportunities across Kenya, and launching Eden Life Kenya, the company can now expand its geographical reach as well as its approach to cultivating a personnel network.

Lynk was winding down when Eden Life approached: it had shut down its website, halted new services, completed all pending orders, and transitioned laid-off staff by helping them land jobs at other companies. For Eden Life, the acquisition is an opportunity to test its model in a different market, with experienced hands to ease the transition.

“The ability for a venture-backed and rapidly expanding young business like Eden Life to come into a new market proves that its market viability is very ripe and rich,” Eden Life Kenya Country Lead (and former Lynk employee), Akinyi Wavinya Ooko-Ombaka, tells TechCabal on a video call.

Before transitioning to Eden Life Kenya, Akinyi was Lynk’s Acting Director for Operations for their B2C services, where she managed its workforce of gig workers. Prior to that, she worked on standardising Lynk’s products and oversaw operations at the Lynk Academy, a platform where Lynk monitored, evaluated, and upskilled its gig workers.

This acquisition has paved the way for Eden Life to move into the gig economy space, in a way that it hasn’t been able to in Nigeria. Launched in April 2019, Eden Life started out as a home management service, helping busy Nigerian professionals, primarily middle-class millennials, to organise their lives by connecting them with professional home managers. The services were subscription-based; customers paid a monthly fee that ranged from ₦24,500 ($59) to ₦126,000 ($300), depending on the level of services.

Similarly, Eden Life Kenya will be subscription-based, with a monthly plan of meal delivery, laundry, and cleaning services going for Ksh. 15,400 ($132).

Eden Life’s expansion comes at a time when the market for home cleaning services is seeing major growth. Data from the Economist Intelligence Unit shows that Africans—particularly those in the middle and upper class—spent $83 billion on home cleaning services in 2016 alone, a 219% increase from the amount spent in 2011.

Meanwhile, Lynk, which began operations in 2015, had successfully bridged the gap between service providers and customers by building the entrepreneurial infrastructure many informal workers lack.

According to a press release sent to TechCabal, before winding down, Lynk had facilitated over 50,000 jobs and transferred $4.5 million to more than 2,000 workers across 4 main verticals: beauty and wellness; cleaning and care; installation, repair and maintenance; and furniture and decor.

Eden’s expansion plan

The Kenyan expansion is just a starting point for Eden Life’s broader vision to significantly improve Africans’ quality of life over the next decade through saved hours and overall convenience, Akinyi says, hinting that the company is looking to enter 8 other African cities over the same 10-year period. (She declined to elaborate on which cities when asked by TechCabal.) The company’s success in Kenya, she added, will give them the oomph to replicate elsewhere.

During Lynk’s wind-down process, the company helped former staff move to Lynk’s partner companies and placed some gig workers in partner companies such as BuildHer. Eden Life Kenya hopes to absorb the others. Meanwhile, Akinyi and one other operations staff member transitioned to Eden Life Kenya. Akinyi explains that Lynk didn’t only allow her and her colleague to continue their jobs in different capacities but championed their specific understanding of service delivery in Kenya.

Once the acquisition was complete, Akinyi and the other former Lynk employee travelled to Nigeria for a 3-week embed with the Eden Life team to better understand the ins and outs of the company. While Akinyi acknowledged that Kenya’s market is different from Nigeria’s, she believes Eden Life shares Lynk’s aim in addressing similar challenges, like inconsistencies among providers’ levels of services and pricing.

She adds that being immersed in Eden Life’s culture helped her and her colleague contextualise and connect with the company’s vision and values, and how they drive growth. The visit also filled a knowledge gap when it came to different services the startups offered. For instance, Lynk did not have experience setting up a commercial kitchen or delivering finished food products to customers the way Eden Life does. Akinyi says it was important to see that process in real time.

“Something else we’re taking from Eden Nigeria is that very complex understanding of how systems change not only based [on] market but based [on] the type of product and service that’s being delivered,” she adds.

Eden Life gig economy play

Over the years, Lynk has trained hundreds of service providers through its academy, connected those providers with customers, and maintained a robust database of both. Akinyi explains that that database now belongs to Eden Life.

Before acquiring Lynk, Eden Life had a different approach to personnel. Instead of in-house training, the company sourced service providers from partners that recruited and trained individuals on home management skills. Eden Life then ran background checks on potential service providers, hired them as in-house professionals, and dispatched them to attend to customers.

Akinyi believes the kind of labour that many of us refer to now as “gig work” has existed in Africa long before the term entered the tech lexicon. Akinyi believes that for Eden Life to expand to other African markets, it needs to engage workers from the informal sector, those with specialised vocational skills who provide services such as cleaning, repairs, and maintenance.

But Akinyi maintains that not all of Eden Life’s services lend themselves to this kind of engagement. The company won’t, for example, outsource meal deliveries or laundry services to individual workers but would instead process these requests in-house to maintain efficiency, quality control, and oversight.

“The infrastructure that exists to deliver to our quality standards just isn’t as developed for us to hire contract individuals at the moment,” she says. This quality control and oversight process is especially crucial when it comes to the logistics related to meal services like food sourcing, compliance with health and safety regulations, and a uniform plating process to ensure customers receive consistent meal portions.

But when it comes to other services like beauty, cleaning, and repair and maintenance, Eden Life recognises the potential in engaging gig workers. As Eden Life expands into more services, they will use a distributed model, engaging with the worker to deliver services as Lynk did.

“It’s more scalable to be able to tap into the individual worker that is not necessarily tied to the company versus [employing] 1,000 people to deliver 1,000 jobs,” Akinyi explains.

Akinyi remains rooted in her belief that the future of concierge services in Africa cannot thrive without informal workers, whether they are trained within a company as in-house employees or engaged on a contract basis.

“Any startup that is trying to deliver essential services cannot exist in this market without engaging the individual gig worker,” Akinyi says.