When Syrian entrepreneur Ronaldo Mouchawar founded Souq.com in 2005, buying things by clicking a picture on a clunky computer was unheard of in the Middle East. Somehow, Souq managed to quickly become the leading online retailer in the Middle East. And in 2017, twelve years after it launched, Amazon bought it for $580 million to expand operations in the Middle East and North Africa.

Today Egyptian sales make up more than half of Souq’s revenues.

Souq’s $580 million buyout underscored Amazon’s online retail expectations in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where e-commerce continues to grow at 25% every year. Bain and Company say the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Egypt, with its 103+ million residents, make up roughly 80% of the e-commerce market in the MENA region.

Furthermore, a Disrupt Africa report released in January shows that 20% of Egyptian startups are decidedly pursuing opportunities in the e-commerce and retail-tech space. That is roughly two times the number of fintech startups operating in the country and a sharp contrast to the rest of the continent’s startup profile. Last year, Egyptian e-commerce startups received USD$ 131.27 million; according to Africa: The Big Deal, which is 1.4 times the e-commerce funding Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa received in the same period.

Clearly, retail tech and e-commerce rule Egypt’s tech scene; and this is why.

Government policy is pushing informal SME retail online.

Facing a budget deficit of $27.8 billion in May 2018, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi offered five-year tax exemptions while urging informal workers to legalise their status. The government had hoped to raise an additional $51.9 billion in taxes from the informal sector. At a parliamentary session, Mohamed Badrawi, a member of the Economic Affairs Committee, declared that “Incorporating all these economic activities into the formal sector is becoming an urgent matter.”

The informal sector in Egypt accounts for more than half of Egypt’s economy. In 2020, the government issued a new law that offered incentives for small businesses to incorporate as formal entities. Beyond creating incentives for informal traders to formalise operations, Egypt’s Central Bank imposed daily limits on cash deposits and withdrawals while asking banks to remove similar daily limits on digital transactions. The bank says this will help support financial inclusion goals. In reality, however, this push saw informal traders who generate bulk sales in cash struggle to deposit and withdraw cash, as a result, pushing them to formalise their businesses. When these traders incorporate and begin to accept digital transactions, it also makes sense to take their business online.

Photo: Alex Azabache/Unsplash

The functioning belief on the part of the government was that e-commerce would aid a transition away from cash dependency, which will, in turn, reduce the size of the informal sector and increase tax revenue.

Covid-related restrictions accelerated consumer trust in digital commerce channels.

The social and economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated digital transformation globally. Egypt was not an exception.

Despite the government’s best-strong-armed efforts (it mandated the use of cashless systems to pay for government services and imposed fines on defaulters), Egyptian shoppers remained reluctant to use digital channels for shopping or payments – until the COVID-19 pandemic

This was also partly driven by the reforms mentioned earlier which the Egyptian government used to encourage informal retailers to formalise their operations. At the time, Egypt’s Central Bank waived several bank transaction fees for 6 months which it later extended to the middle of 2021. As a result, despite predictions about slowing digital commerce growth in Egypt, Jumia and Noon reported a 940% increase in online sales as the pandemic hit. 72% of participants in a Mastercard survey claimed to have shopped online during the pandemic.

The trend appears to have sustained beyond COVID-19 as more people than ever use smartphones to access services. Today Egyptian e-commerce is expected to grow at least 30% this year, buoyed by younger shoppers and rising incomes from Egypt’s expanding middle class.

Good infrastructure is good business.

Photo: Fady Fouad/Unsplash

As e-commerce accelerated in Egypt, it created a ripple effect on the logistics sector. People who buy things online need to get their goods delivered somehow. While infrastructure in Egypt is not the best globally, Egyptian infrastructure is second only to that of the island nation of Seychelles on the Africa Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI).

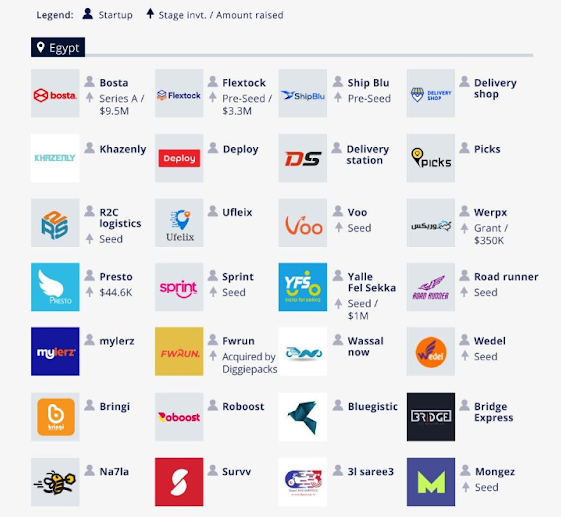

A combination of a reasonably good road network and increased investment in transport and telecoms infrastructure is proving beneficial to the handful of logistics-tech startups that are helping to make shopping online easier.

Still, as with online retail anywhere, last-mile logistics remains an issue. According to Waya Media, 40% of online orders in Egypt do not reach their customers the first time they are shipped. So while Egypt’s 4000 post offices make up the backbone of its distribution network, a good number of online retailers who need to deliver items to their customers’ doorsteps partner with full-service logistics companies or use smaller specialized delivery units that stitch together end-to-end services to patch delivery gaps.

Source: Open Data for Africa

Other startups like Appetito are pioneering franchised pickup centres similar to what Getir does in Europe to bring grocery deliveries closer to their customers. More prominent players like Amazon opened a 28,000 square meter warehouse in the 10th of Ramadan City in August last year. The new hub and 15 delivery stations across Cairo, Alexandria, Tanta, Ismailia, and Assiut are part of Amazon’s growing MENA distribution network.

“[BNPL will] accelerate moving from cash-on-delivery to paying by cards”

– Sherif Nessim, Founding General Partner, Jedar Capital

The e-commerce boom is also creating ripple effects for fintech in Egypt. While cash-on-delivery is very much alive, the value of card transactions is growing at an impressive pace. The Egyptian central bank is playing a leading role in facilitating this shift. For example, it allows banks operating in the Egyptian market to own unlimited shares in payment service providers and payment systems operators as part of the country’s push towards cashless payments.

Sherif Nessim, Founding General Partner at Jedar Capital, believes that Buy Now Pay Later offerings can help accelerate the transition to digital payments. “Every year, we find that the balance is moving from cash-on-delivery to cards, cash to cards. People are putting more trust in online payment methods,” BNPL solutions, he adds, “[will] accelerate moving from cash-on-delivery to paying by cards because if I pay with this credit card, I can pay in 6 months, interest-free.” When you think about it, it makes sense for a market where younger and relatively more impulsive shoppers are the drivers of e-commerce growth.

According to Nessim, all of these plays are part of why he expects growth to continue for traditional e-commerce and q-commerce companies.

Attractive growth prospects lure VC money.

2021 was a record-setting year for venture-backed companies globally. Venture capitalists invested more than USD$ 675 billion into startups globally, and Africa outdid its 2019 record with more than $5 billion invested in African startups. Venture funds were themselves swamped with cash, partly a fall out of fiscal (stimulus) policies for the pandemic and partly as a result of more people being willing to bet on risky “companies of the future” than ever before.

All of this activity has set the perfect stage for venture capital funds in Egypt. Last year and led by funding into e-commerce and retail tech companies, Egyptian startups raised $403.5 million, according to data from Disrupt Africa.

With more cash to spend, investor packs are hunting for growth and returns in emerging and frontier markets. Post-revolution Egypt happens to be one of the latest such frontier markets. Naturally, investors have their eyes on it. “They realise that the next ten years are the years for emerging and frontier markets,” Sherif Nessim says. He adds that some VC firms he knows are creating dedicated funds “that only invest in emerging markets rather than invest out of their global funds.”

On the other hand, like Amazon and Souq illustrate, bigger growth-hungry companies in the United States and Europe prefer to acquire local companies in emerging markets instead of building from scratch.

Egypt’s unique combination of growing venture capital interest, growth prospects, and a government determined to shore up revenues by including more informal businesses means digital commerce will continue to grow as more retailers become formal and come online. At the same time, it also signals significant growth prospects for affordable business-to-business software and services to help these newly formal businesses manage their processes and access credit.

Critics have slammed MENA investors for mostly backing e-commerce and marketplace startups. However, by helping buying and selling thrive online, those investments may be responsible for accelerating digital adoption in other areas in a region as conservative as the MENA. After all, since commerce is the backbone of the world’s economic systems, it only makes sense for the digital version of the bazaars and souks that line Egyptian streets to lead the way for her technology ecosystem.