So this happened…

Given the Apple/FBI fight, @stevekrenzel at @codeorg made this fun app on App Lab to show how encryption works: https://t.co/nKMSntcl5n

— Hadi Partovi (@hadip) February 22, 2016

In light of the Apple/FBI conflict, a former Twitter, Google and Salesforce software engineer named Steve Krenzel, wrote an app to show everyone (who didn’t understand it before now) how encryption works.

Information is said to be encrypted when it is converted into a code, especially to prevent unauthorized access.

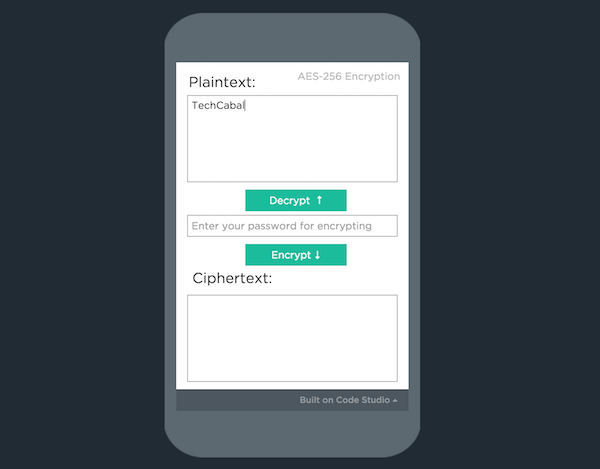

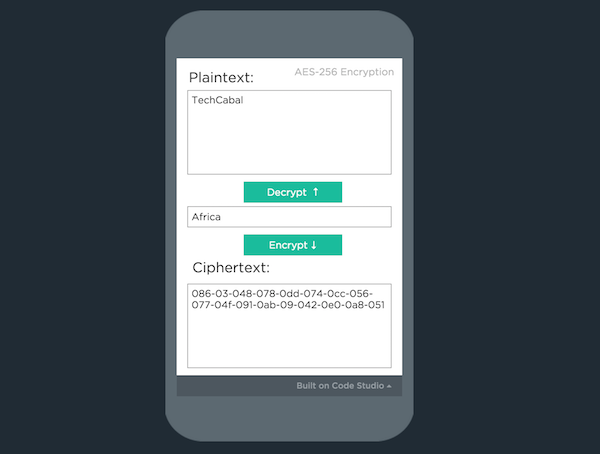

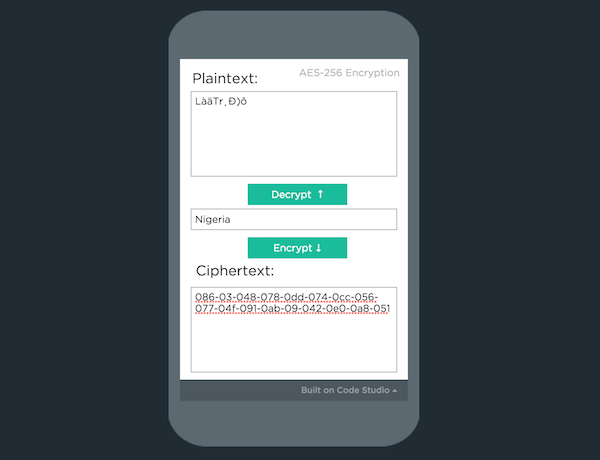

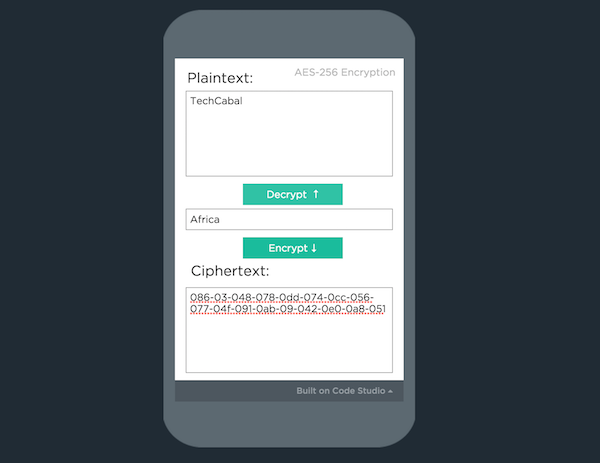

Steve’s app, EncryptMe, has 3 text fields: plaintext, password (or encryption key) and ciphertext. The plaintext is the message you’re trying to encrypt, the ciphertext is the unintelligible code that gets displayed to everyone who isn’t authorised to view the plaintext, and the password is, well, the password that gives you access to the original, decrypted message.

You’d have to be living under a rock not to have heard about the Apple-FBI encryption situation. But for the benefit of the more…lithodomous…amongst us, I’ll do a (not-so) quick recap.

Late last year (December 2, 2015, to be precise), 14 people were killed in a terrorist attack at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, California. Both of the attackers were killed in a 5-minute police shootout soon after. An iPhone 5C belonging to one of the shooters, Syed Farook, was later recovered. The FBI wants access to the data on the device to see who the attackers were communicating with – potential accomplices and all.

Under normal circumstances, it shouldn’t be an issue. The FBI can retrieve this information from iCloud (via an auto backup) without a warrant, but the iCloud password was erroneously reset by country officials. Now the only way to retrieve the data on the phone is by entering the passcode. That’s a pretty simple thing to do, asides from the fact that the person who set the code in the first place is…you know…dead.

Now, the FBI wants Apple to remove the limit on the number of passcode attempts, the auto erase feature, and possibly write a new (insecure) version of iOS and install it on Syed’s phone so they can retrieve his data. Apple refused the request, saying that “complying with the order would have “implications far beyond the legal case at hand”. Basically, conceding to open up “just this one iPhone”, will bring a flood of requests from other governments, for other iPhones. Obviously, many of such requests will not be as innocent, or well-meaning as this one seems.

Since the matter came to the public domain, it’s caused a dichotomy. Tech companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft have sided with Apple, while Bill Gates, Donald Trump (of course) and many other American citizens have taken up with the US Government. The conversation is no longer about one iPhone – the US government wants access to a couple others, as well. It’s also brought to light, a much larger conversation, privacy vs. security. If you care for the finer details, you can get them here.

Photo Credit: Yuri Salmoilov