The fear of cash

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, African governments

worked with providers to waive mobile money transaction fees. By the end of March, Kenya and Ghana were some of the countries that had made the move.

There were also telco-led efforts; for example, MTN implemented fee reduction across a number of its markets including Uganda, Rwanda, Zambia and Cameroon.

The consensus is that digital payment is a valuable tool for preventing the transmission of the virus. It allows people to maintain social distancing while avoiding, to a great degree, the use of cash, which could serve as a vector for the spread of the virus.

A tale of two countries

In Kenya, Safaricom waived fees for 3 months

following a directive from the President and a meeting with the country’s central bank. President Uhuru Kenyatta asked that they

“… explore ways of deepening mobile-money usage to reduce the risk of spreading the virus through physical handling of cash.”

And the waiver by Safaricom was a sacrifice worth $51.64 million.

The telco announced that it expected to forgo 7.3% of MPesa’s annual revenue as a result of fee waivers. One could argue that it might have gained new users as a result of the waiver or seen an increase in transactions.

On the other hand, an impending economic crisis affecting their income might have forced some users to avoid paying fees while seeking other means to conduct financial transactions. Perhaps many people would have hoarded cash as research focused on some advanced economies is now showing. This essentially justifies the sacrifice made by Safaricom. But there’s a bigger case for aligning with policies that support the adoption of mobile money.

Mobile money is more than a tool for curbing the spread of a virus. In some countries, it is the only means of payment for many people. Consequently, and most importantly, it has been a good tool for financial inclusion.

It has been 3 months since Safaricom made the announcement. Its mobile money service is the market leader in Kenya and now the central bank in a press release says the waiver was beneficial.

“A significant increase in the use of mobile money channels by individuals in both value and number of transactions was noted,” the Central Bank of Kenya said.

Its press release further noted that 1.6 million additional customers began using mobile money although there was a marginal decline in business-related transactions.

The bank noted that most of the increase was in low-value transactions of $9 or less. Low-value transactions, it highlighted, account for 80% of mobile money transactions. It announced a 3-month extension of the waivers. It is unclear to what extent the waivers have helped cement Safaricom’s dominance. News reports this week say MPesa has a 98.8% market share as of March 2020.

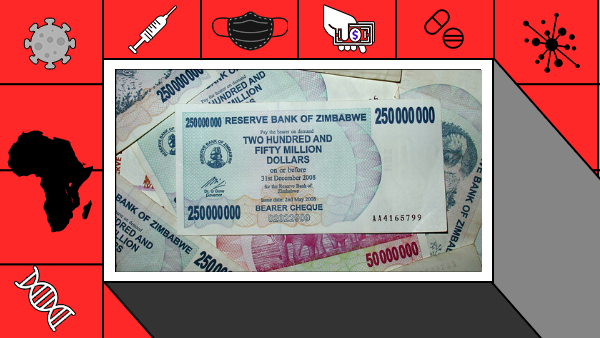

In Southern Africa, there’s a different story in Zimbabwe. The government has basically banned mobile money platforms!

It also banned trading on the stock exchange stating that it

“is in possession of impeccable intelligence” that shows “mobile money systems of Zimbabwe are conspiring, with the help of the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange, either deliberately or inadvertently, in illicit activities that are sabotaging the economy.”

The government’s aim is to stop the decline of its currency’s value. The country has a number of monetary challenges including growing inflation and a paralyzing shortage of foreign exchange.