The BackEnd explores the product development process in African tech. We take you into the minds of those who conceived, designed and built the product; highlighting product uniqueness, user behaviour assumptions and challenges during the product cycle.

—

A good way to gauge a person’s financial state is to find out what they can buy in one installment.

If I’m able to comfortably pay for a car and a home at once, it paints a certain picture of my bank account. It suggests I don’t lose sleep over ordering my scale of preference.

For most people, that’s a theoretical picture that never comes alive.

In reality, most African households and individuals do not have enough money to satisfy necessities or buy assets that would improve their productivity. People often know what they need but lack the ability to fill it.

One such need is energy. Low income families either find themselves cut off from main power grids, or cannot afford the costs of being on the grid. Yet, they need electricity. If not for refrigeration or entertainment, at least to light up their homes and charge their phones.

A decade ago, some Kenyans would spend up to 20% of their income on kerosene and charging their mobile phones alone.

M-KOPA’s pay-as-you-go solution

In 2011, M-KOPA started designing a solution to this energy problem. The Kenya-based company observed how conveniently people exchanged small amounts on Safaricom’s MPesa, either to transfer money or pay for goods, using their basic feature phones.

They saw how this micro-payments culture could be extended to a credit system that helps people access solar energy services according to their means (“kopa” means “to borrow” in Swahili).

Because low income households typically prioritize food but need energy, a micro-payments system could enable them to have both without breaking their budget. Provided they have a minimum level of income that will enable them to pay for the services in small installments.

M-KOPA began their pilot in October 2012 with a product bundle that included a solar panel, three lamps and a kit for charging phones.

Customers made an initial deposit of KES2500 ($25 at the time), with subsequent daily instalments of KES40 (about 40 cents at the time) via MPesa. Payment was spread over a year.

After eight years, M-KOPA has extended this micro-credit system beyond energy products, defining itself as an asset financing company rather than a solar energy company.

In January, they partnered with Safaricom to launch a pay-as-you-go plan to help Kenyans buy Samsung smartphones. They have rolled out the service in Uganda and Nigeria in the months since and have sold 100,000 smartphones, according to Rolake Rosiji, the company’s Nigeria country manager.

But how are they able to provide credit in Africa where the trust infrastructure (addressing, identification) is too weak to track people in rural areas? Here comes the tech.

Remote control, through the cloud

At the time of writing, M-KOPA’s products page features four main items: solar lighting equipment, television sets, refrigerators, and smartphones made by Samsung and Nokia.

All four are available in Kenya, their oldest market. The smartphones became available in Nigeria in the first week of September.

The company sources their products globally, and tweaks them to their technical specifications, Rosiji tells TechCabal.

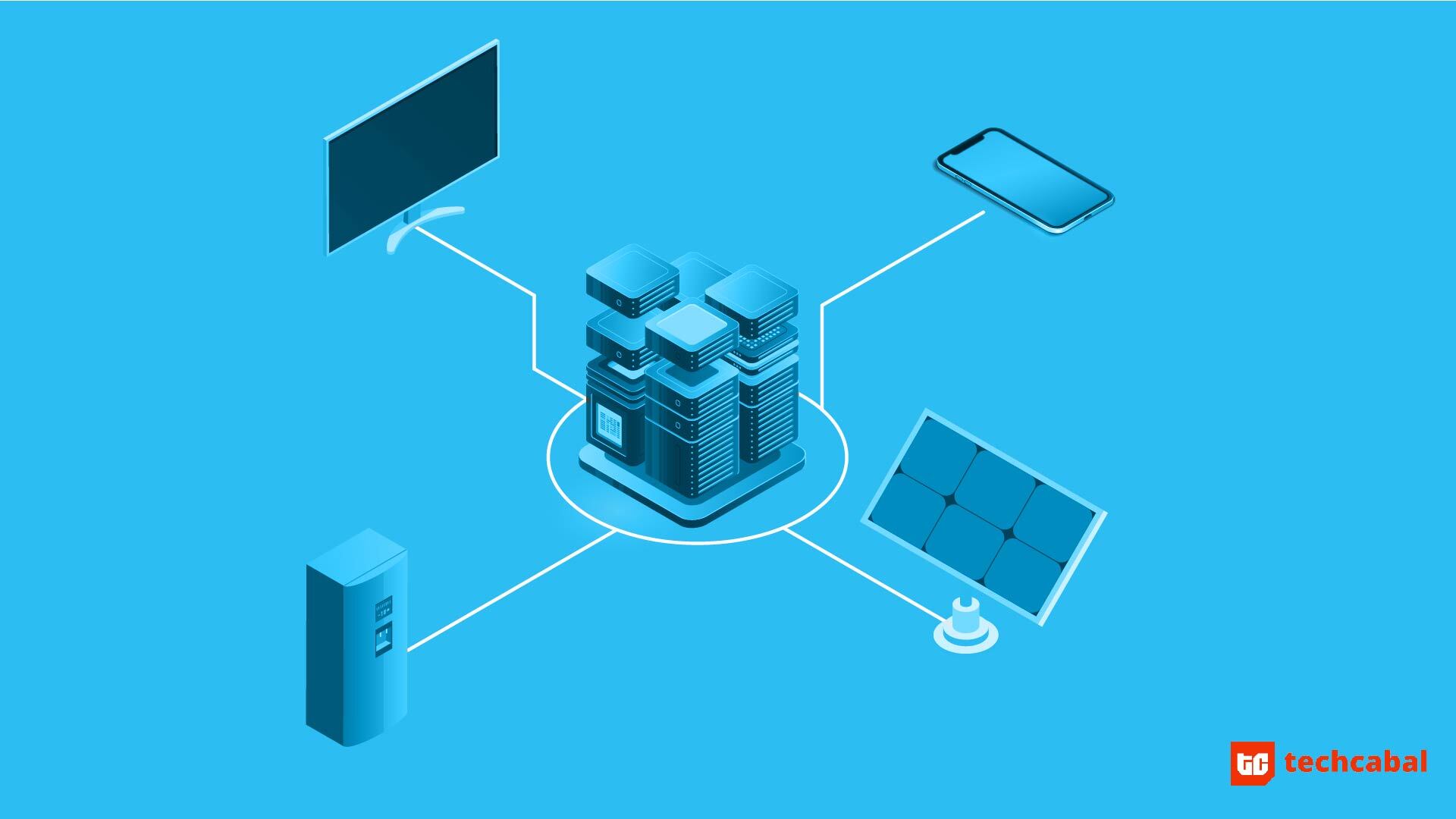

These may be different electronic products but M-KOPA has a common system for providing them to potential users on a pay-as-you-go purchase model. It is based on an internet-of-things capability by which the company remotely monitors and manages the user’s device.

Every M-KOPA device – phone, TV, or solar kit – comes with a SIM card. To get anyone of these, a customer is required to make a down payment (KES 3,999 for a smartphone, ~$37), then make subsequent weekly payments for a duration of between nine and twelve months.

Each device is connected to M-KOPA’s CRM system by IoT. When the customer is unable to make a payment for some reason, they can be automatically locked out of using the device.

For the smartphones, the lock is enabled by an interaction between M-KOPA’s proprietary software and a lock feature in the smartphones. A 2G connection is required to operate the smartphone.

Customers can temporarily unlock the phone for five minutes each day to access specific URLs.

Because the payments are designed to be automated, M-KOPA does not take cash or bank transfer payments.

That means mobile money transfers in Kenya and Uganda. But with the absence of a strong mobile money network in Nigeria, they have partnered with Paystack and Interswitch to enable electronic transfers.

Taken together, what you have is a technically sophisticated credit system with built-in fail-safes to ensure user accountability.

Leaning into smartphones as a platform

By organising payments around the mobile phone, M-KOPA gives the user easy access. By automating the payments and connecting each device to a control room, the company is able to track its assets and drive repayment for the credit offered.

Rosiji is optimistic that the smartphone financing plan in particular could become a product that attracts Nigerian users towards the other electronic products. Since launching in Nigeria about two years ago, her Nigeria team has grown from one staff to around 40 (excluding sales staff).

There are about 40 million smartphone users in Nigeria today, with adoption projected to increase to 140 million by 2025. Nigeria is also one of the poorest countries in the world; 40% live below the poverty line, according to the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics.

It’s easy to see why M-KOPA senses an opportunity in the country with the smartphone financing plan. The company estimates that 80% of its solar products customers live on less than $2 a day.

Despite their lowly financial status, those at the bottom of the economic pyramid aspire to live better lives and have tools to increase their productivity. They want to set up businesses, connect their children to learning facilities and live healthier lives.

Being able to access a smartphone can be a step towards attaining those life-changing aspirations. The evidence of smartphone growth in Africa and other emerging markets suggests as much.

Poverty alleviation vs financial inclusion

But M-KOPA will have to contend with a perception problem; that their value proposition is either insufficient to move the needle for the poor or that they are trying to build a venture-backed billion-dollar company on the needs of poor Africans, as this Bloomberg piece suggests.

Rosiji’s explanation is that M-KOPA’s mission is not to alleviate poverty but to grant access to finance to people who would otherwise not have access in the formal financial system. Tying the finance to assets instead of offering cash ensures credit is put to best use.

Tying credit to assets appears to be a useful counter to how some users use lending apps; borrow money for financial “needs” but spend it on sports betting.

Ultimately, users will decide whether the financing plan is a good deal for them. M-KOPA projects they will hit one million users across their various products this October.

It remains to be seen how adoption would be outside of East Africa where mobile money has been integral to M-KOPA’s success, and whether Nigeria’s poor consider this their best route to owning a smartphone and ascending the urban mobility ladder.