Kareem (not real name) is a taxi driver in Uganda. His regular customers usually contact him via WhatsApp, and so he needs constant internet access. However, it has become increasingly harder to do so with the introduction of Uganda’s tax on the use of over-the-top (OTT) platforms like WhatsApp.

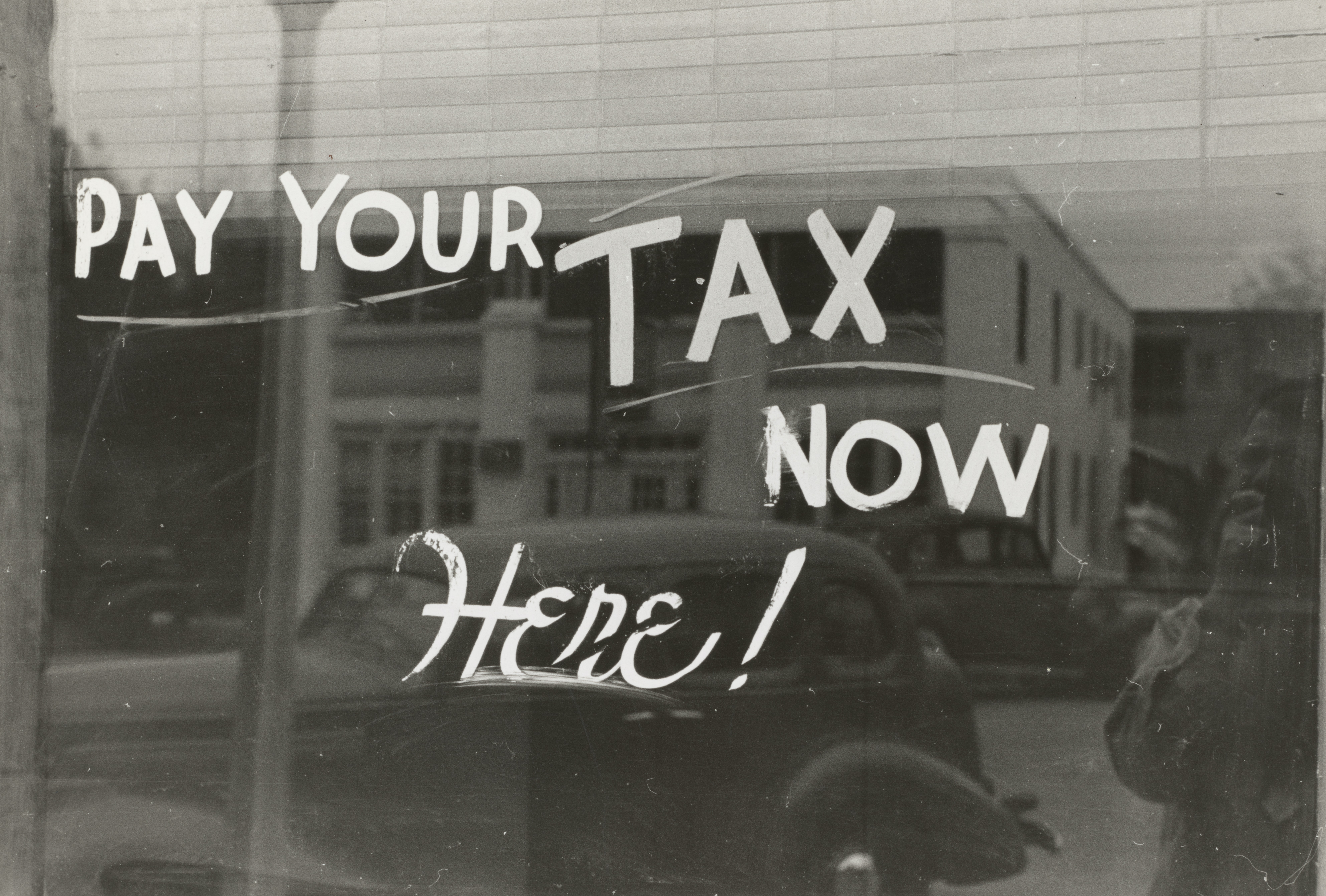

In May 2018, the Ugandan government passed a law imposing a daily levy of 200 shillings ($0.09) on users of “over-the-top” online services including Facebook and Whatsapp. The government said the tax was to raise revenue and to curb “idle talk”. Following the implementation of the tax, 74% of individuals who used social media for their businesses reported a reduction in income.

A closer look

Uganda is not the first to tax digital services. In 2014, South Africa implemented a 14% value-added tax (VAT) on digital imports, making it the first African country to introduce digital taxes. The Zambian government announced a daily tariff of $0.03 on internet phone calls in August 2018.

In March 2018, Tanzanians woke to a law requiring online content-creators to pay a licensing fee. Now, this was interestingly three-fold, meaning that they first had to pay an application fee of 100,000 Tanzanian shillings ($43), an initial registration fee of 1,000,000 shillings ($431), and then an annual registration fee of 1,000,000 shillings. Basically, to run a blog in Tanzania, you’d be looking at a fee of about $905. For context, Tanzania’s GDP per capita as at 2019 was $1,122.

Kenya and Nigeria are also following in these steps. While Kenya’s Finance Bill will impose a 1.5% tax on the gross value of digital transactions, Nigeria’s Finance Act attaches a 5% VAT to all online transactions starting from January 2020.

Revenue generation or social media restriction?

While taxes are undeniably a large source of revenue, they are also an effective way of stifling digital activity. The Ugandan government called it curbing “idle talk”. The definition of that isn’t clear, but here’s what is: before the tax, 33% of internet users used social media platforms 10 times a day. After the tax, this percentage became a paltry 6.6%.

The tax sparked a protest tagged #ThisTaxMustGo, but the tax didn’t go. A similar protest tagged #TaxePasMesMo (Don’t Tax My Megabytes) started in Benin after the government introduced a 5% VAT on the use of OTT services and a charge of CFA Francs 5 ($0.008) per megabyte. This protest was successful as the government reversed the tax.

This revolutionary power of social media may be why governments are trying to suppress its use; sometimes they use taxes, other times they use internet shutdowns, but they still do the same thing – reduce online activity. However, the economic case for them appears to be strong. For instance, as at February 2019, South Africa had raised R3 billion ($185m) in digital tax revenue. Nonetheless, using digital taxes as a revenue booster is a short-term solution that will only create bigger and long-term problems.

Long-term effects on the digital economy

“Digital taxing is myopic. It shows that African governments are not getting it right and are not seeing the bigger picture of what is possible with the digital economy,” says Boye Adegoke, Senior Program Manager at Paradigm Initiative.

“They are quick to want to have a slice of the cake without really figuring out how their respective countries can fully maximize the opportunities that exist within the digital economy,” Adegoke added.

Africa’s digital economy is set to hit over $300bn by 2025. These taxes are counter-productive for the sector. In Uganda, within two months of implementing the social media tax, the internet penetration rate had fallen to 35% (13.5 million users) from 47.4% (18.5 million users) the previous month.

The long-term growth of the digital economy should be the focus for African governments, and it will not happen without the presence of available and affordable internet. Digital taxes keep people away from the internet and increase the cost of accessing it.

According to a report by the Alliance For Affordable Internet, Africans already face the highest connectivity costs across the world, with 1GB of mobile data costing up to 9% of the average users’ monthly income, much higher than 1.5% of monthly income in Asia.. These high costs contribute to a digital divide in Africa that digital taxes will only widen. The question is – How many people can Africa afford to keep offline?

“When you look at the digital economy, there is so much that can be achieved that is not happening because of lack of sufficient government investment in terms of infrastructure, and in terms of policy to make sure that the ecosystem is really conducive for business and growth,” Adegoke explains.

“Governments should instead focus on deepening internet access; more people need to get connected and should be able to afford to stay online. That is when we can fully realize the potential in the digital space,” he concluded.

Perhaps the only way these taxes can contribute to the digital economy is if governments pour the generated revenue into building digital infrastructure, improving digital literacy, and supporting innovation. Unless that happens, the digital economy will continue to struggle under the weight of taxation.

Editor’s note: This is a TC Insights data article. TC Insights clarifies the business and human impact of technology and innovation in Africa with research and data. Find out more about our work here. Got a request for us, let us know here.