On Wednesday, Kenya’s 12th parliament passed the controversial 2020 proposal that seeks to regulate “anyone who employs technologies to collect, process, store or transfer information for a fee”.

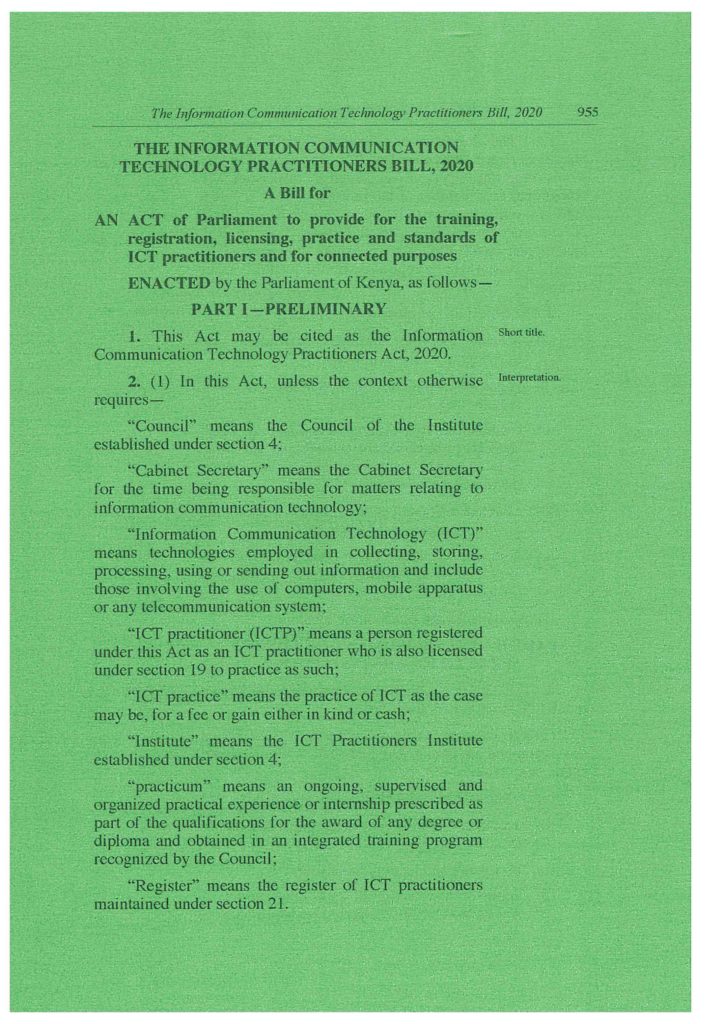

First introduced in 2016 by majority leader, Aden Duale, and supported by Kenyan MP, Godfrey Osotsi, the wide-sweeping and vague ICT Practitioners Bill mandated the registration and licensing of vaguely defined “ICT practitioners” by a council. According to the 2016 proposal, individuals who sought registration with the council needed to have completed a university education with at least 3 years of relevant experience and would pay an annual license fee. The proposal also outlined jail terms and fines for individuals who failed to comply.

Needless to say, the proposal drew an outcry from the country’s tech community and was reportedly withdrawn after Joseph Mucheru, Cabinet Secretary in Kenya’s Ministry of Information and Computer Technology, rejected it, noting that proposals in the bill would affect innovative talent and alienate local youth from lucrative online jobs, educational and investment opportunities. At the time, Mucheru had said, “If enacted, the ICT Protection Bill 2016 will cause duplication in regulation and frustrate individual talents from realising their potential.”

That was in 2016.

Two years later, in 2018, a member of parliament who was nominated to represent workers, Godfrey Osotsi, reintroduced the bill with an amendment that simply loosened the eligibility requirement for ICT professionals. Now instead of being required to have graduated from a university, a proposed ICT Practitioners Council would determine who got registered.

In 2018, the bill was also rejected.

Again, 2 years later in November 2020, the bill was reintroduced with superficial amendments that removed degree requirements, jail terms, and fines for people who fail to register.

Almost 2 years later, this Wednesday in a sleepy parliamentary session, and with one day to go before the 12th parliament closed shop for the term, the bill was quietly passed and now awaits presidential assent.

Who is supporting this bill?

While the bill has generated outrage from stakeholders in Kenya’s tech community, there is significant support from a raft of tech professionals. In 2016, the Secretary-General of the ICT Association of Kenya (ICTAK), Kamotho Njenga, released a statement supporting the bill. “Once enacted,” the statement read in part, “the various provisions enlisted will go a long way not only to elevate the standards of ICT practice in Kenya but to also avail a blueprint that will help counter multiple challenges that accompany emergent technologies. By creating a registration framework, the bill injects professionalism and introduces a culture of accountability within the industry as the country gears towards an ICT-driven economy.”

Paul Macharia, a health informatics consultant supports the proposal. “Having worked in the ICT space for over 15 years, I know we needed a regulatory body like yesterday.” he opined. He says the bill will ensure standards of competence, allow governments to keep a register of all the professionals that meet these standards and deal with the professionals that fall short of these standards.

Both Macharia and the ICTAK’s points are the standard arguments of the proponents of the bill. But Kenya already has a Computer Misuse Act and a Cyber Crimes Act—both wide-sweeping laws that regulate the use of technology in Kenya, so it is not clear how or why another law is needed to stop the so-called quacks from operating. Besides this, the bill does not disclose how the council would issue accreditation for ICT professionals or provide the criteria to be used in determining if an individual is of good moral standing.

That “quack” classification is also problematic. Information technology is one of the most dynamic and fast-growing spaces globally. Unlike civil engineering or medical health, for example, a software developer does not need to be certified to build software. Indeed many of today’s widely used tech products are built and maintained by unlicensed developers. No country has the sort of national ICT licensing programme that this bill proposes.

But Macharia contends that Kenya can lead the way, “Sure! Kenya being the first is a great thing,” he wrote in a LinkedIn comment. “We could set the pace/standard on how ICT professionals work.”

A black spot for Silicon Savannah

A loose alignment of tech stakeholders and professionals who have been fighting the bill since its debut in 2016 disagree.

In a draft counter-statement to the ICTAK’s 2016 declaration seen by this writer, the group wrote, “Registering of practitioners does not necessarily lead to professionalism and accountability. ICTAK has not cited any direct evidence that registering of practitioners affects the overall quality of services provided to customers by members of a regulated profession.”

The statement continues, “Almost every ICT job is conducted within the confines of “contracts” that define the responsibilities of parties involved, hence ensuring accountability. What values shall this bill add to the accountability of ICT practitioners, that is beyond the scope of contracts we sign today as we go about our duties?”

Kenya’s government says that its Long Term Development Blueprint, Vision 2030 will make the nation a globally competitive and prosperous nation by promoting “local ICT software development,” and making ICT Software more affordable and accessible”… gatekeeping can have serious adverse effects on its nascent tech ecosystem.

Members of the group also organised a petition which garnered over 14,000 votes at the time and succeeded in getting the bill withdrawn twice. But the almost comical and steady 2-year-gap-march of the bill appears to have won out—at least in parliament.

Stakeholders now fear a presidential assent on the bill could seal what has been described as rent-seeking behaviour.

“The reason why I think the bill is detrimental is that innovation is about thinking outside the box,” Sheena Raikundalia, Director of UK-Kenya Tech Hub told TechCabal, “it’s not about your degree or paper certificates. Some of the best techies I know are self-taught! Tech moves so fast, [that] by the time you finish your degree what you learnt is outdated. This is taking a step back.”

Affectionately described as Africa’s Silicon Savannah, Kenya is one of the Big Four technology heavyweights in Africa. As recently as last month, Microsoft and Google set up new offices in Nairobi, global card payment association, Visa announced that it had opened an innovation hub—one of only 6 in the world, and Amazon announced plans to open an Amazon Web Services (AWS) local zone in the country. These are all a significant testament to the East African nation’s tech reputation which also ranks 4th on the list of African countries with the most professional developers only behind Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt.

Kenya’s government says that its Long Term Development Blueprint, Vision 2030 will make the nation a globally competitive and prosperous nation by promoting “local ICT software development,” and making ICT Software more affordable and accessible”. But in a heating tech talent market, poorly thought out regulation that looks, to all intents, like pure gatekeeping can have serious adverse effects on its nascent tech ecosystem. Right now Kenya is distracted by its upcoming national elections, and reports of social media-fueled hate speech and misinformation are increasing. Those are important areas for regulation; deciding who is qualified to build a mobile app is not.