Data protection rules are one reason prior attempts at forming an anti-fraud posse failed. But everyone knows the real reason is that leaders of fintech firms simply don’t trust each other.

After an ₦11 billion fraud case hit eTranzact in 2018, several senior leaders of the online payments company—one of Nigeria’s oldest—elected to resign. eTranzact’s managing director, Valentine Obi, chief technology officer, Richard Omoniyi and head of operations, Kehinde Segun stepped down from their roles alongside two executive directors.

The eTranzact affair—which was perpetrated by the chief executive of a client firm—bears little resemblance to the numerous fraud attempts payments companies in Nigeria face today. Instead, the significance of the news in 2018, to anyone paying attention, was that tech-enabled financial services fraud could be very costly. ₦11 billion in 2018 was the equivalent of almost $31 million. It also highlighted the fact that fintech firms could not be too vigilant.

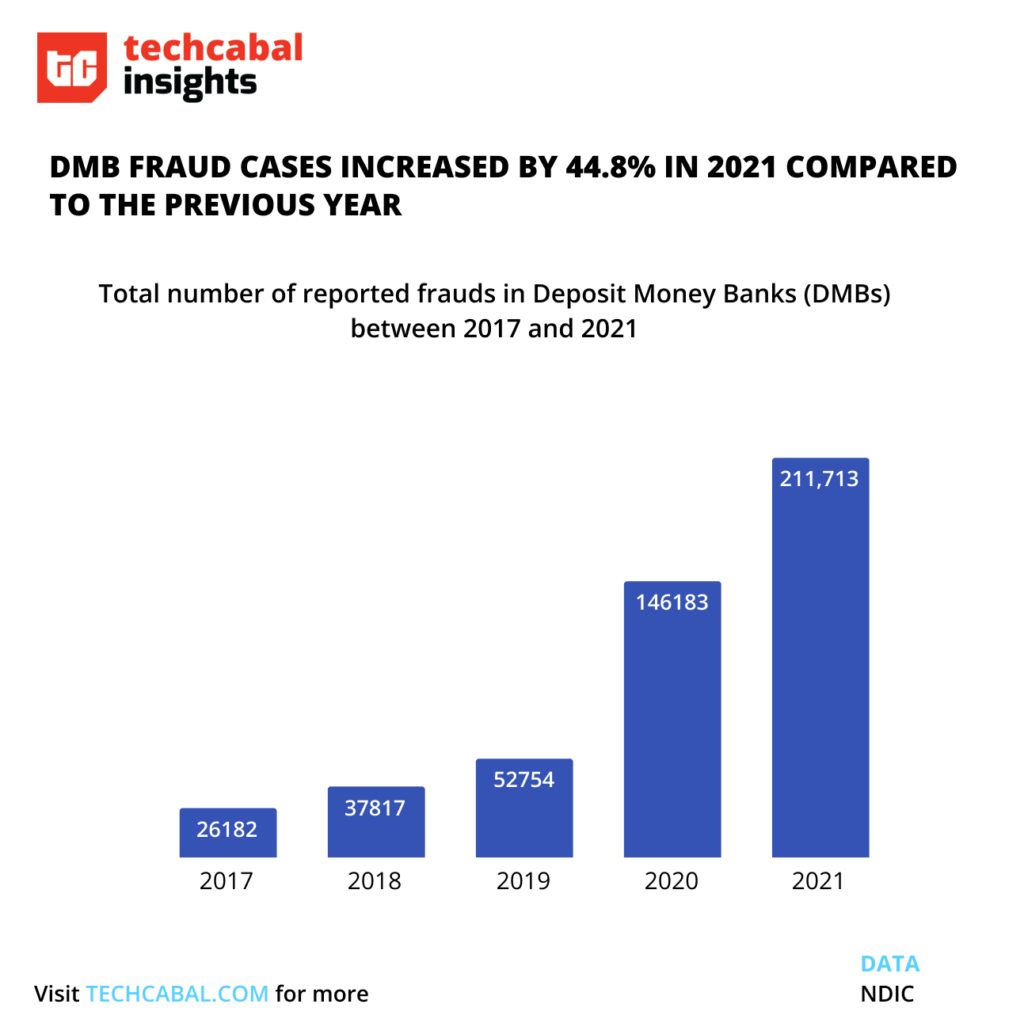

Between 2020 and 2021, fraudulent activity recorded by deposit banks in Nigeria rose to 211,713 —a 44.8% jump, according to data from the Nigerian Deposit Insurance Scheme (NDIC). According to Smile Identity, a KYC provider, fraud attempts increased by 50% between the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2022. The first half of 2022 alone recorded a 30% increase compared to the same period in 2021. In the first nine months of 2020, cybercriminals had an astounding 91% success rate from over 46,000 attempts.

The growing complexity of cyber fraud

Cyberfraud risks are a constant headache as more people use digital channels for transactions. In June 2022, MTN’s mobile money service sued 18 Nigerian banks after it lost ₦22.3 billion ($53.7 million) to mobile money fraud. MTN’s loss dwarfs what eTranzact lost in 2018 and involved more people—MTN says the amount was transferred in error to 8,000 accounts—a pointer to the growing scale and complexity of cyber fraud. Last year, Union54, a Zambian fintech was forced to halt operations over an attempted $1.2 billion chargeback, TechCrunch reports.

More recently, Flutterwave lost N2.9 billion ($6.3 million) and another N550 million ($1.2 million) per reporting from Techpoint Africa and TechCabal. The company says it only discovered unusual trends in several user accounts during a routine check of its transaction monitoring system, but claimed it did not lose any funds. However, it asked banks to block hundreds of bank accounts amidst legal action to recover an undisclosed amount from the affected accounts. The Flutterwave incident is at least the equivalent of a generous seed round, or two — in today’s sour venture market.

Now Flutterwave and 12 other firms that receive or process payments online are reportedly creating a data-sharing initiative to prevent fraud incidents by sharing data. Project Radar, Semafor reports, will “enable companies to pool details, including banking and government identity data, of individuals and groups that have attempted or made fraudulent transactions.”

Will data sharing among fintechs stop fraud?

Esigie Aguele chief executive of VerifyMe, a KYC software provider is emphatic, “Absolutely, yes! The way to solve it, even if you look at developed ecosystems [is that] private sector creates federated environments for fraud reporting,” he says when asked if he believes if fraud networks can help prevent fintech fraud. “The definitive answer to the question is yes, and it literally is the only way. The question now is what type of network? What is the infrastructure of the network? How is it built? What is the regulation under it?” he adds.

Sharing data to stop fraud has been discussed since at least 2018, possibly earlier, with little to show for it. “When financial service providers (FSPs) share data, they are positioned to better identify patterns that suggest transaction fraud, leading to fewer false positives in the detection of financial crime,” says Jacqueline Jumah, Director of Advocacy and Capacity Development at AfricaNenda, a digital payments-focused research and advocacy group.

While the benefits of sharing fraud detection data is clear, Ademola Adekunbi, a data protection lawyer and compliance professional says fintechs “are reluctant to share [fraud data] because of data privacy concerns,“ but also because they do not want their peers to discover the true state of fraud attacks they face. Payment companies are also wary about data sharing initiatives because they do not want to expose their fraud detection methods, Adekunbi adds.

Nigeria’s fintech space is intensely competitive as a result. “It is not in the interest of fintech firms to share data that might potentially expose their fraud detection system to their competitors,” says Adekunbi, and Jumah agrees. “A majority of FSPs are not comfortable with disclosing valuable competitive intelligence on their customer transactions, nor creating tensions with data privacy regulations.”

“Nigeria’s new open banking rules will allow anyone to build fraud prevention solutions,” Omoniyi Kolade, founder and chief executive of SeerBit, a payments software company tells TechCabal. SeerBit’s CEO, however, wants the push for fraud data sharing to come from a regulating body. But it is not clear if the rules which allow customers to give third parties access to their banking information extend to allowing financial services institutions to trade data on cyber fraud. Service providers will also have to contend with Nigeria’s data privacy laws.

Institutionalising data sharing to prevent fraud

According to Semafor, Project Radar is currently in talks with the Nigerian Interbank Settlement System (NIBSS) and commercial banks in Nigeria to track and report fraudulent bank transactions in the country. But there are pitfalls to be aware of. For example, a transaction can be suspicious without being fraudulent. There is also the risk that fraud and defaulting on digital loans may both be treated as cybercrimes. As a result, users who default on loans could, in theory, be locked out of digital financial services, especially if these anti-fraud lists are shared by credit providers and payment companies. Unlike seeking to fraudulently pilfer funds from unsuspecting users or financial firms, failing to pay back a loan is not a criminal activity. But financial services practitioners point out that serial defaulting is also a fraud tactic. In some cases, however, bad actors are able to take loans using stolen identities only for unsuspecting victims to discover the fraud when loan providers come calling for repayment.

Adedeji Olowe, founder and chief executive of Lendsqr, a digital credit firm in Lagos, does not believe Project Radar will work. When the chips are down, “everyone will want to see the other person’s data but refuse to share their data,” he believes. “It is not the first time,” he tells TechCabal. Separately, Olowe has made the case—on his blog and in conversations with TechCabal for the central bank to open its global standing instruction (GSI) facility to fintech firms. The global standing instruction is a set of rules and technology that allows banks to deduct the balance of a loan from any other accounts owned by their debtors. Allowing fintechs to access GSI may help separate debtors from being added to fintech fraud lists, as digital credit companies will be able to collect defaults from any other financial account linked to the defaulter. This would at least theoretically address Adekunbi’s concern that the lack of distinction between cyber fraud and loan defaults could result in defaulters being listed as cybercriminals.

Fintech companies like Flutterwave are not the only firms forming a posse to share data in the hopes of preventing fraud. The Association of Data Verification Service Providers (ADVSP) of Nigeria, made up of licensed ID Verification operators in Nigeria (also known as KYC companies), are working on building a fraud environment to share data. “Nigerian KYC companies are coming together to share data to prevent fraud for our customers. This is also a very powerful area where you would see a lot of change in the coming months as well,” Aguele reveals to TechCabal.

Is there a way forward?

Adekunbi believes that the only way fraud data sharing can work without compromising user privacy or inadvertently exposing IP is if the responsibility sits with an independent body. “The way [fraud data sharing] can work is that there has to be a central repository where people can share data on customers who trigger fraud flags and the data will be accessible to all participants.”

New research from Deloitte and the World Economic Forum points at how fraud data can be shared without compromising privacy or sharing trade secrets, including applying differential privacy rules and federated analysis methodologies to prevent any one party from abusing data. “Federated analysis could be used to create master fraud detection/prevention models across transactions, without ever sharing the underlying customer data across institutional lines,” Jumah says.

The point is clear, the secrecy within the fintech space is needless, especially with advances in technology. Instead of going it alone or forming industry cliques, fintech firms can push for extant rules like the ones for Open Banking to allow the creation of an independent body to coordinate fraud data sharing.

In a LinkedIn post detailing how cybercriminals are increasingly turning to Race Condition exploits to steal from fintechs, Opeyemi Awoyemi, a managing partner at Fast Forward, a venture studio, notes that “scammers are sharing information on new vulnerabilities among themselves, while fintechs and banks often lack the same level of communication and collaboration.”

If fintech firms do not trust each other enough to openly collaborate and fight what is perhaps their biggest shared enemy and a serious friction point for their customers, how can they demand trust from users?