In March this year, Naspers shut down its R1.4 billion venture capital fund slash accelerator, the Naspers Foundry. The reason given for its unexpected sunsetting was that the “global investment environment, as well as the local SA one, has changed and we have made clear the need for our business to adapt,” a spokesperson for the company said.

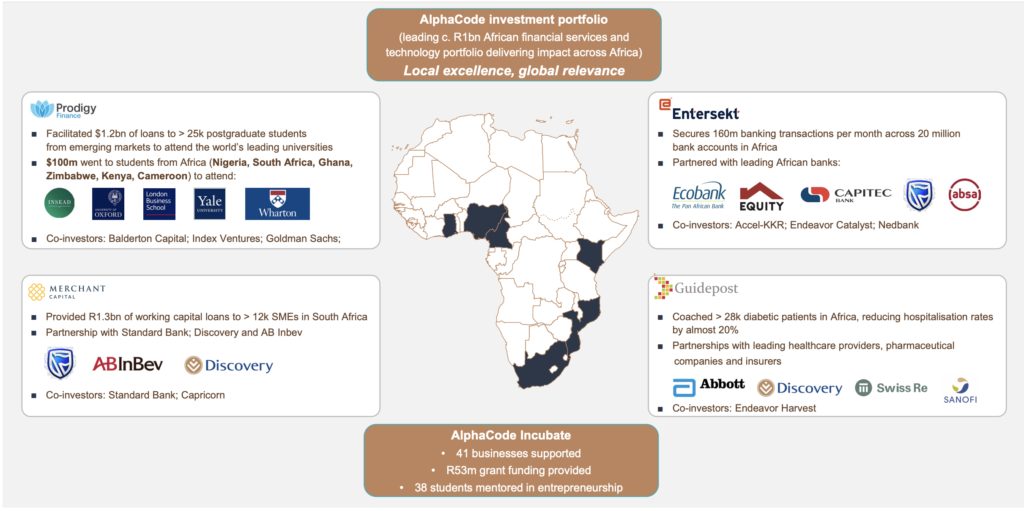

Just a few months earlier, Rand Merchant Investment Holdings (RMI) had also shut down its accelerator slash incubator AlphaCode, one of the most prominent in South Africa.

The closures come at an unfortunate time when the South African tech startup ecosystem could do with such structures. Over the last few years, South Africa has slid down the ranks of the most attractive venture capital destinations on the continent, being eclipsed by the likes of Nigeria, Egypt, and Kenya.

“Incubators and accelerators for vital businesses that do not have a lot of resources. Through these structures, entrepreneurs gain access to tools and mentorship and support that can help move their businesses a bit further. They are an essential vehicle to truly help small businesses and startups move forward,” said Xoliswa Moraka, founder and managing director at Colab4Growth, an entrepreneurship development consultancy firm.

The important role an accelerator plays in the lifecycle of a startup is reiterated by Will Green, program director at Grindstone, a Cape Town-based accelerator which has accelerated over 124 startups. Green is also CEO of Co.lab, a holding company for collaborative ventures.

“Accelerators provide startups with knowledge, market access, networking and funding. These are vital in taking an entrepreneur’s idea from startup to scaleup,” he stated.

Why are accelerators not working in South Africa?

According to Naadeya Moosaje, co-founder of WomHub, a Cape Town-based innovation coworking space running incubation and acceleration programs for women entrepreneurs, the lack of sustainability of accelerated startups is a major factor contributing towards the failure of such initiatives.

“The challenge is that you have so many accelerators; because they incentivise through the black economic empowerment codes, rather than being entrepreneurs first. So for them, having entrepreneurs on a programme, regardless of the sustainability of that business, is part of the business model of the accelerator. This means they don’t really care about what the product outcome is going to be. They are just happy that they actually have an entrepreneurship programme,” Moosaje said.

Moraka, on the other hand, believes that the trend of copying global accelerator models without regard for applying them to a South African context is contributing factor to the trend of failure of accelerators in the country.

“You have to understand who you are dealing with. If you are creating an accelerator model, you have to take cognizance of who you’re supporting, and the environment and the conditions of where these people are coming from. So you can’t really do a cut-and-paste model to say it will work because it has worked overseas,” she said.

The other issue pointed out as a contributor to the low rate of success of accelerators in South Africa is a lack of alignment between the corporates who support accelerators and what it takes to facilitate the success of a startup.

Moraka noted, “In a corporate accelerator program, at the end of the day, the corporate itself is looking to extract some sort of value either through exiting the accelerated business or whichever way. But the problem is success for a tech startup is a risky and long-time bet. Sometimes in that case, there is a misalignment between what and when the corporate wants a return on its investment and how startups work.”

Phiwa Nkambule, a startup mentor, venture builder and founder who has been through numerous accelerator programs, agrees that a lack of understanding by corporates on what defines success in a startup and what it takes to achieve that success is a contributing factor in the failure of startups.

“Some accelerators in the country do a good job of providing training but a terrible job at providing resources. One of the most prominent corporate-backed accelerators in the country which shutdown gave access to training and networks but limited capital access to a few startups who won pitch competitions. This meant that the startups from the program could not scale which means the corporate could not get a return via an exit and hence could not reinvest in the program to keep it running,” he said.

Other ecosystem players believe that the inability of the ecosystem to learn from the failure of past accelerator programs is the reason why the failure rate of accelerators remains present year after year.

“There’s a number of failures that have come and gone but no reporting and accountability mechanisms are in place to learn from these failures. We don’t have experienced programme operators who know what it takes to make a success story out of an accelerator. There are entrepreneurs who get burned by these programmes but they just quietly disappear into the ether, never to be heard from again. This means all the lessons they learnt from those failures are not known and end up just being recycled in new programs,” said Vuyisa Qabaka, partner at HYBR group, an innovation consultancy firm.

Fixing the system

To fix the accelerator model in South Africa, Moosaje believes that it is best for corporates to collaborate with experts in startup development instead of trying to run their accelerator programs themselves.

“If you look at the incubators and accelerators that are going bust, they are mostly corporate-backed. Wouldn’t it be best for these corporates to invest the money in an existing structure which has the personnel and experience to bring out the best results? In my opinion, going this route would be cheaper in the long term for the corporate looking to set up such a program,” she said.

Mooseja believes that adopting such a model would also prevent the current trend where the incubators and accelerators tend to not be entrepreneurs-first but more focuses on ticking racial and gender diversity and inclusion boxes.

She adds, “I have seen incubators and accelerators who have taken ESD (enterprise and supplier development) funds by virtue of saying they support female and black entrepreneurs through their programs. But the issue is that they end up not doing much to support these groups of entrepreneurs, which defeats the whole purpose of these ESD initiatives.”

The need for entrepreneur-centric accelerators and incubators is reiterated by Octavius Phukubye, a venture capitalist at pan-African VC firm Microtraction.

“There is a huge need & gap for (1) incubators & (2) accelerators that are founder & venture centric. Each time I see founders who’ve come out of existing ones as part of my VC or startup pitch judging work, I still notice huge development gaps – both at venture & founder level,” he said on a LinkedIn post.

For Moraka, the success of incubators and accelerator programs in South Africa hinges on completely rethinking the current models and going back to the drawing board to build structures that can actually produce tangible results.

This process, according to her, should involve the prioritisation of comprehensive business development investment strategies that facilitate the creation of high-impact and high-growth startups.

“I think there is a need for engagement and communication of all players in the ecosystem to say, ‘hey, let’s rethink what the accelerator model in South Africa needs to look like.’ Many accelerators have failed to deliver on their promises to open markets for these startups. They have just become glorified classrooms where these innovators sit around to listen to stuff they could easily just find online. This does not benefit either the entrepreneur or the ecosystem as a whole,” she said.

In Qabaka’s view the only way to fix the current accelerator model in South Africa is to put in place effective and efficient reporting and accountability mechanisms which will ensure that the structures do what they were meant to and that, even if they fail, the mistakes are recorded so that they are not repeated in future programs.

“Some of these programs use BEE codes under the guise of supporting disadvantaged entrepreneurship but that “support” does not translate to any tangible results. There must be reporting and accountability mechanisms to ensure that these programs produce startups which would contribute greatly towards employment creation. Without enforceable KPIs, we are just going to keep singing this same song about the lack of impact of South African accelerators in the ecosystem,” he stated.

As someone who has been both on the side of the entrepreneur as a founder and also on the side of the accelerators as a mentor and venture builder, Nkambule believes that fixing the accelerator model in South Africa is going to require an understanding of how exactly an accelerator is supposed to work.

“I think there is a lack of alignment in the ecosystem between what an accelerator is supposed to be and what it is. Some of these structures market themselves as accelerators but when you look at their operations, there are more like incubators,” Nkabule noted.

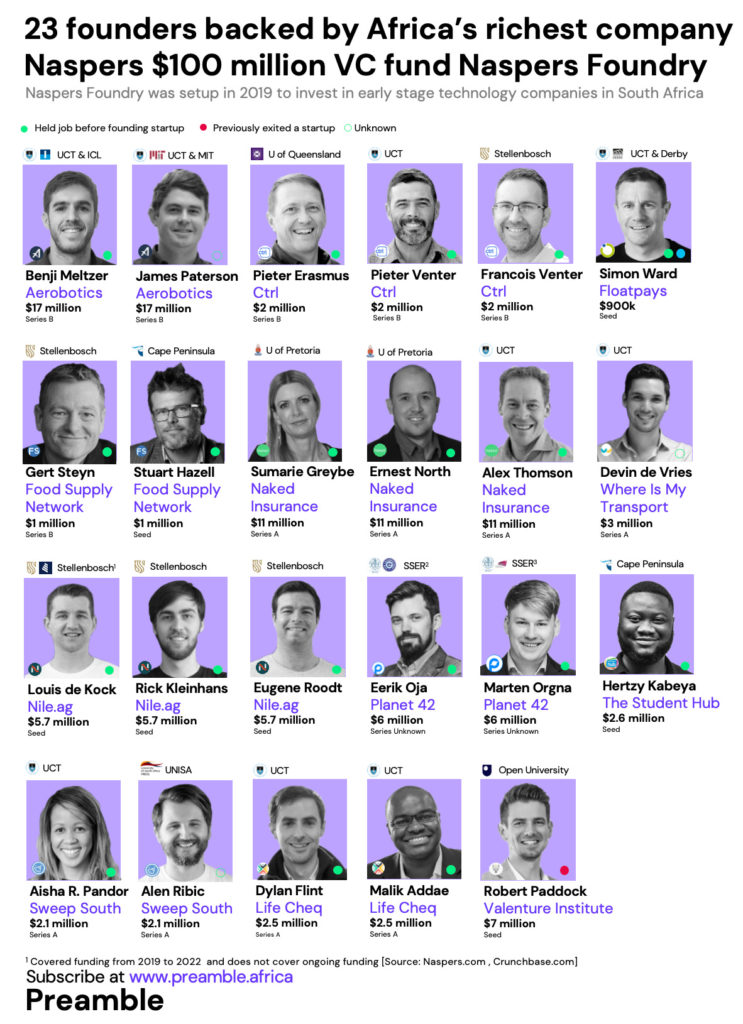

Despite the obvious issues that blanket accelerators in South Africa, the value that they bring to the ecosystem cannot be overstated. Before its bowing out, AlphaCode was one of the most esteemed accelerators in the country’s ecosystem, creating recognisable alumni such as crypto exchange Luno and agritech startup Livestock Wealth. Naspers Foundry too had its fair share of success stories, including Floatpays, Naked Insurance, and Planet42.

To ensure that the current and future accelerators do not meet the same fate as Foundry and AlphaCode, there is a need to address issues such as misalignment of objectives between corporate-backed accelerators and their beneficiary startups, numerous barriers to entry into accelerators by qualifying startups, and lack of accountability and reporting on lessons learnt from failures of other accelerators.

Even with a receding venture capital industry in the last few years, as Africa’s most industrialised nation with an advanced tertiary education sector, banking systems and entrepreneurship ecosystems, as well as direct air access from North America, Europe, and Asia, South Africa will always be in a good position to bounce back.

Fixing the accelerator model to ensure that it creates an enabling environment for innovative companies to prosper will be an important way of aiding this revival.