More and better data is good, but not enough. The why and what happens after are equally, if not more important.

Last week, my colleague at TC Insights, the research arm of TechCabal, penned this brilliant read discussing how a lack of data in Africa might impact the prospects for African startups. Writing about data availability and accessibility pushes a lot of the right buttons and some of our readers wrote back with insightful comments. Victor Mosengo, a data scientist complained about the hurdles facing anyone who attempts to close the data gap:

For example, in a jurisdiction where trade administration is a regional function, a company/org seeking to utilise trade data will now need to either:

- Seek permission to be a data processor only in the administrative units they have engaged

- Lobby the national government to kick off a process of data custodianship, which then opens a debate of regional autonomy, and after all this, then hope the national government can allow them to be a data processed

- Rely on surveys and desktop research; most fall back on this as the most practical approach.

As someone who dabbles in market intelligence beyond desktop research, I fully understand Mosengo’s point. Navigating all of this complexity makes research expensive and laborious, especially if you seek to build representative intelligence. With some capital and political savvy, you could find a workaround. But you would not have solved the data problem. Because getting data is still on the lower rung of the bigger problem, which is creating fit-for-purpose solutions. The bigger problem lies in what happens after you have data.

Unless this “huge gap is fulfilled, collecting and gathering a mountain of data will yield no benefit or result,” Naushad Kermalli, a Dubai-based banking and capital markets consultant wrote to us in a response to last week’s essay. Here’s one manifestation of this problem.

Partner Content:

This Wealth Management Startup, Twinku is helping Nigerians Organize, Plan, Manage their Financial life Better

How many people live in Lagos?

In the previous week, I followed (as I’m sure some of you will have) the debate, if you could call it that, about how many people live in Lagos. Everything from the staid rational to the weirdest extrapolations has been offered by experts and online trolls. The debate about the population of Nigeria’s commercial nerve centre inspires wild responses because of what happens after this data point is established. Why exactly do you need this data as a government? Why does Business X need this data? Why does Organisation Y need this data?

Unfortunately, the answer and primary use of data points like this in Nigeria (and a handful of other African countries) is political and the business lobby is largely uninterested. If Lagos has more people than Kaduna (a northern Nigerian state), then it gets more political representation and, ostensibly, more capital resources from the national government. If Nigeria has more people than Egypt, Nigerian diplomats can use the phrase “most-populated African nation”, even though it means nothing and carries little significance, geopolitically speaking.

Because this is the central aim for collecting basic foundational data, the incentive to be accurate may not be a priority. One effect of this is often that the data collected is not extensive enough. How could it be if the main (unstated) aim is political bragging rights?

And this is only about basic foundational data. Data relating to market opportunity, like income levels and how they change over time in response to, or to cause, economic shifts also suffers from the challenge of what happens after. The answer a lot of the time is nothing. This dislocation between data and policy or decisions is a symptom of another problem. This problem is that we do not appear to care much for learning as a core activity for social progress.

The learning problem

Learning means the ability to modify behaviour, acquire skills and develop preferences based on new knowledge. It is an inbuilt human function. Literally! Your skin, eyes, ears, nose and tongue are foundational learning tools built into our sense of being and human function.

Learning is also a great discomfort. Who hasn’t stubbed a toe, suffered an indigestion or struggled with some maths?

Learning is the why we collect data—to acquire skills and develop preferences. If we have a data problem in Africa, it is because we have a failure of systemic learning. At the higher academic levels, how much learning happens relative to Africa’s societal ambitions? Do we even have enough social ambition as a collective? In business, the story is not much different. In everyday life, learning often happens organically. In business you will often have to seek it out intentionally.

Learning is found in translation

We focus so much on the problem of collecting data and very little on the easily solvable problem of translating what we already know into structures that can be used. Granted a lot of the time, what is already known is only known by a few people/organisations who are often physically and mentally divorced from the challenges that they could help solve. Very often it is basic data that is essentially useless because it cannot form a narrative that is coherent enough for public policy or private enterprise.

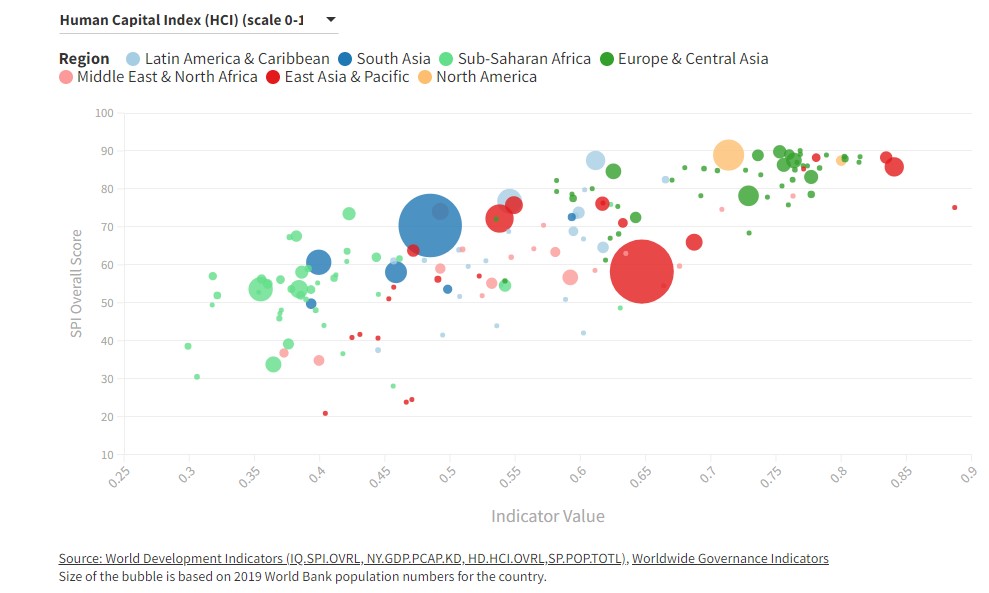

The World Bank says Statistical Performace Indicator (SPI) scores are “strongly correlated with several leading development indicators, such as GDP per capita and indicators of human capital or government effectiveness.” This means that the extent to which a country collects and uses data will show in development outcomes like Human Capital Index, GDP per capita and Government Effectiveness indicators. On a 0 to 1 scale for the Human Development Index, most African countries score below the 0.50 mark. (See chart below. Explore the data yourself).

Data only has value if it are used. Overall African countries rank between the 2nd quintille and the bottom 20% in Statistical Performace. Only a handful rank above this including Egypt, Tunisia, Ghana and South Africa. Source: World Bank Statistical Performance Indicators.

Tajikistan (GDP per capita $897) for example, is marginally better than Nigeria (GDP per capita $2065) in terms of how well it captures and uses data to support Human Capital development. Even Afghanistan scores better than Nigeria (0.39 versus 0.35). Overall Nigeria sores better in statistical capacity, but translating that capacity to outcomes is where it performs woefully. So why gather more data if what you have is groslly underused? This does not mean of course that more and better data is not needed. Infact part of why the current data is underused is because it is either inaccurate or outdated and lacks additional data context (i.e., it is not networked enough) to make it useful

Fixing the data gap in Africa will be a journey of learning new numbers and new systems of agglomeration. But, more importantly, it will mean being able to translate data into action and decisions. Sitting on top of the best datasets benefits no one. Eventually, it becomes useless because data only finds meaning when it is networked.

We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.