Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of any organisation I may be affiliated to

Recently, the Nigerian Communications Commission (“the Commission”) opened a stakeholders’ consultation for the purpose of establishing an Internet Industry Code of Practice (“the Code”). The Code according to the Commission is borne out of the need to promote and safeguard an open internet and seeks to among other things address topical internet governance issues such as net neutrality and (discriminatory) traffic management practices by internet service providers (ISPs). The Commission by engaging in this process exercises its internet governance function as provided for in the Nigerian Communications Act (“the Act”), and which is in line with its regulatory mandate to regulate communications services in Nigeria, including internet access services.

In this article, I explain the main regulatory issues of net neutrality and traffic management practices (TMPs) in Nigeria and make policy recommendations on issues pertinent to the net neutrality debate with the expectation that these recommendations will form part of the broader discussions during the stakeholders’ consultation. It is my hope that the final work product of this process would be useful in producing a Code that does indeed foster an open internet as an engine for innovation and socio-economic development.

What is net neutrality?

Net(work) neutrality is the principle of equal treatment between data traffic moving across an ISP’s network. That data traffic is treated equally means that it is treated independent of content, application, service, user device, source and destination. The policy debate on net neutrality seeks to ensure an open internet where internet users are not constrained in how they may choose to lawfully access the internet or in their choice of lawful content on the internet.

According to the Internet Society, the following issues are framed within the context of the net neutrality debate:

- Blocking and filtering: Blocking or filtering of content is a practice in which end users are denied access to certain online content based on regulatory controls or the commercial interest of ISPs or network infrastructure operators to favour their own content.

- Internet fast lanes (or paid prioritisation): The term Internet fast lanes refers to the practice of giving preferential network treatment to certain data streams based on business agreements among ISPs. For example, specific video content might be provided with faster delivery across a network in accordance with contractual agreements between network operators.

- Throttling: The term throttling refers to certain business practices that degrade the quality of data services to end users.

- Zero-rated services: The term zero-rated services describes a general business practice whereby certain Internet content is made available to an end user at a substantially reduced cost or for free. For instance, Facebook Free basics delivered by Facebook in partnership with Airtel in Nigeria.

- Market competition: In markets where users have limited affordable Internet service options, those users are potentially more vulnerable to having their access to available content restricted or to experiencing poorer quality of service. Competition in the marketplace for ISPs is helpful in that it offers consumers a broad range of choice and encourages innovation among service providers.

The relationship between net neutrality and traffic management practices

Within the context of the net neutrality debate lies TMPs engaged by ISPs. TMPs are used by ISPs to optimise the flow of data traffic within their networks. TMPs can be used to implement limiting measures (such as blocking and throttling) and enabling measures (such as routeing, traffic forward and prioritisation).

The net neutrality debate has primarily been a debate about an ISP’s limiting measures. Thus, it can be argued that there exists a close relationship between an open internet as contended by the net neutrality principle; that is an internet where internet users have unimpeded access to all lawful content, because if the quality of service of the internet access service is degraded through an ISP’s limiting measures, the internet user no longer has an unimpeded access, even if the content is nominally available on the internet.

Main regulatory issues in the context of net neutrality and TMPs in Nigeria

It is pertinent to state that the Act does not provide any provision respecting “net-neutrality” or internet “traffic management” practices, neither has the Commission in its administrative rule or decision making referred to any or both of these terms. Nonetheless, certain conducts engaged in by an ISP (or an MNO) are relevant to the net-neutrality debate, and may thus come within the regulatory purview of the Commission. For the purpose of identifying these conducts only voice-over-internet protocol (VoIP) blocking by an ISP, differentiation in the conveyance of traffic of content and application providers (CAPs) on the internet and zero-rating are considered.

First, a vertically integrated ISP providing voice calls through its mobile network has the commercial incentive to block VoIP applications on the internet, which internet users may use as a substitute to the voice calls made through the ISP’s mobile network. The effects of this particular conduct are that the choice of internet users are limited to only the ISP’s mobile network and competing VoIP applications are foreclosed from the relevant market.

From a competition perspective, this conduct constitutes an abuse of a dominant position within the meaning of the Competition Practice Regulations 2007 (the Competition Regulations) if the ISP wields market power. Another example under this head, would be an agreement between an ISP and a CAP on zero-rating a particular application, which conduct has the effect of constraining the internet user’s choice and forecloses competing applications not benefiting from the zero-rating. This conduct constitutes an anti-competitive agreement which is also prohibited by the Competition Regulations.

Another instance is that an ISP’s limiting measures may come within the scope of the Quality of Service Regulations 2014, especially if network performance is degraded to the extent that the minimum quality of service standards for broadband internet service, internet access service or voiceband internet service are not attainable, thus rendering the ISP liable to an enforcement measure by the Commission.

Lastly, a condition in several communications licenses prohibit “undue preference” and “undue discrimination” when providing the licensed service. Although the Commission as at the time of writing has not explained the full breath of this condition, I am of the view that differentiation by ISPs of traffic delivery conditions offered to specific CAPs would be caught by this condition, and by extension the regulatory purview of the Commission.

Policy recommendations

Despite the perceived illegality (or impermissibility) of the foregoing conducts, there continues to exist circumstances in which it may be permissible to implement TMPs. In the light of this, I recommend that the scope of permissible TMPs be guided by the consideration of transparency, innovation, clarity and competitive neutrality. For instance, while it is recommended that the Code set out particular circumstances in which the implementation of TMPs will not be permissible, it should however be noted that there may indeed be “reasonable” or legitimate TMPs such as data compression by ISPs/MNOs to decongest their networks and improve QoS, or when done in compliance of a law.

In addition, commercial practices like zero-rating should only be allowed in circumstances where it furthers public interest or societal goals. While theoretically, as explained above, zero rating may be anti-competitive because of its foreclosure effects on the choice of internet users and competing contents, it is however arguable that it can produce real benefits for internet users especially if for instance it stimulates the uptake of internet access services and/or deepens internet penetration. Another positive is where zero-rated education services on the internet is provided by an ISP as part of its corporate social responsibility strategy. However, all such exceptions to the prohibition of zero-rating in the context of the net neutrality debate must be subject to a very strict narrow review process that will be approved by the Commission in accordance with a bright-line test so as to ensure that the review process is consistent and predictable.

Conclusion

The net neutrality debate continues to be a topical internet governance issue that requires regulatory intervention in several jurisdictions. The FCC in the US has responded through its adoption of the Open Internet Order 2015, while the EC in the EU have enacted Regulation (EU) 2015/2120 on 25 November 2015, to be domesticated across the member states of the EU. In the light of this, the Code and the process leading to its adoption are a welcome development and indicate that the Commission is fully abreast of regulatory developments in the global communications industry. However, the Commission must bear in mind that internet services and indeed the communications industry is in constant evolution so it may be necessary for the Code to be continually updated to reflect market developments.

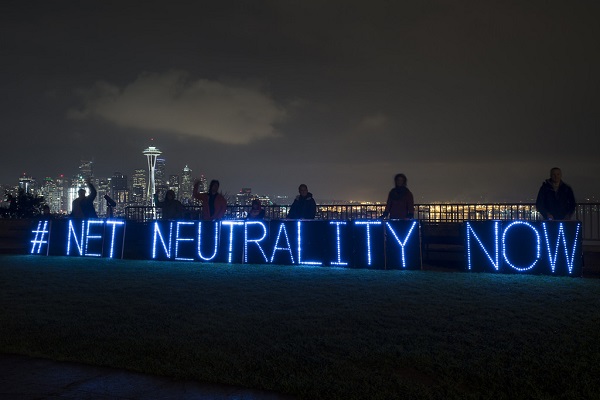

Finally, the Commission in producing this Code must painstakingly strive to balance competing interests at play in other to engender an open internet. As the clarion call for an open internet has been sounded, the Commission must do well to ensure that the internet remains open, now and forever.

Editor’s Note: Chukwuyere is a Senior Associate at Streamsowers & Köhn and the author of “Regulating Anti-competitive Practices in Nigeria’s Communications Sector” (Oisterwijk, Netherlands: Wolf Legal Publishers, 2017).