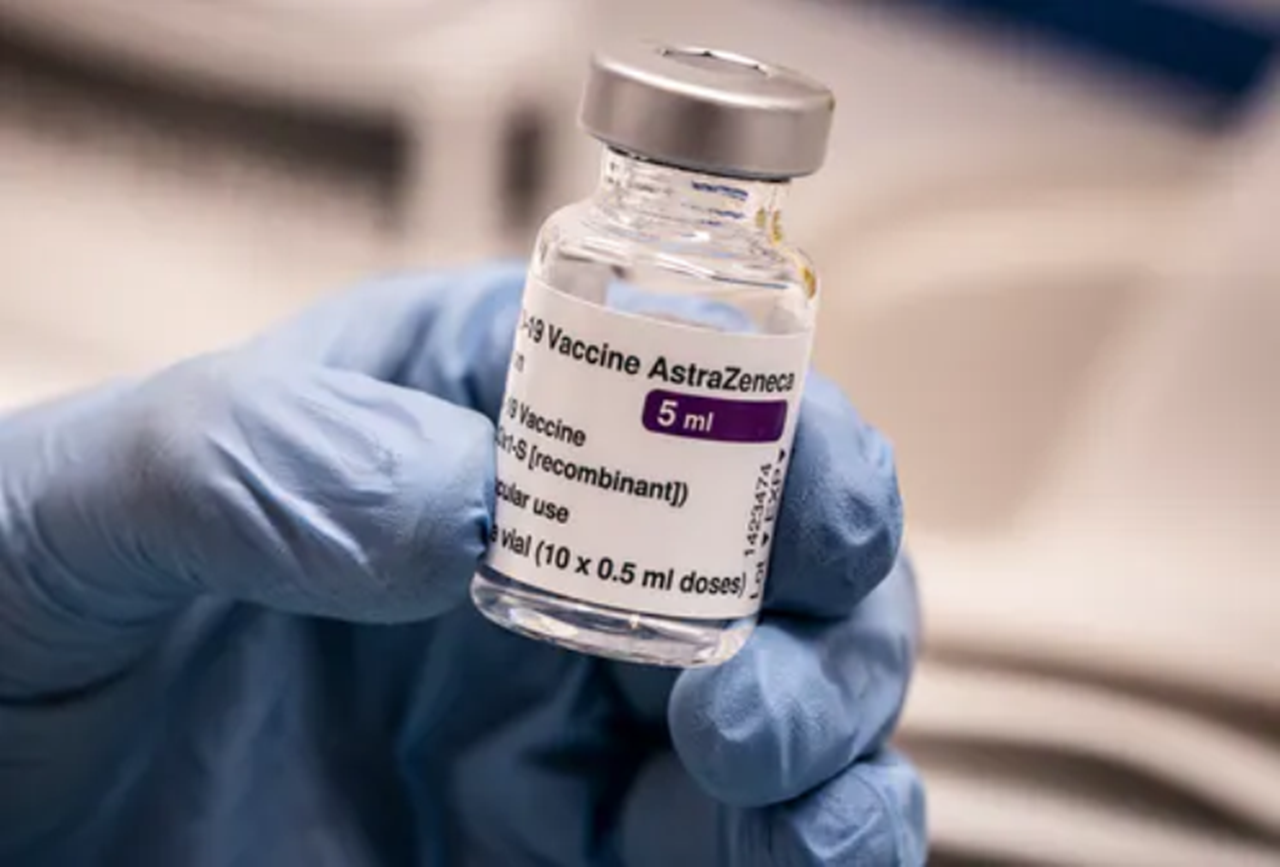

On March 30th, Gregory Rockson, the CEO of mPharma a Ghanaian healthcare startup, announced that it helped the Ghanaian government to receive COVID-19 vaccines. This announcement made mPharma the first company to do this in Ghana and possibly Africa.

In African countries, the procurement process for vaccines has typically been the sole responsibility of the government. This announcement raised questions on why and how mPharma were involved.

In a conversation with TechCabal, Gregory Rockson explained its involvement in vaccine procurement and mPharma’s bigger picture for vaccination in Africa.

Rockson first pointed out that the company’s efforts to support the government started in February 2020, at the start of the pandemic.

“We started by looking at how to improve the testing process. About 40% of healthcare delivery takes place in the private healthcare sector so while the testing was being done for free by the government, it was clear the government couldn’t do this alone,” he said.

The $3 million molecular diagnostic fund

To help support the testing process, mPharma established a $3 million molecular diagnostic fund. The purpose of this fund was to invest in private hospitals in Ghana and Nigeria, helping to equip their existing laboratories with necessary molecular diagnostic equipment to test for COVID-19.

“The biggest gap we saw at the beginning of the pandemic was that our laboratory infrastructure did not have a diagnostic capability. Beyond testing for COVID, most molecular diagnostic work was not happening in Ghana. For example tests like the HPV DNA test and hepatitis viral test only took place in the public sector,” he said.

mPharma created a risk-sharing agreement where the necessary equipment was given to the companies at no cost and no liability to pay back. In exchange, a revenue split was agreed upon for every test done using the equipment.

“So if we provided the equipment and the private hospitals made zero revenue, we got nothing. Back then the government was testing everyone for free. In February, in response to the decision we made, people were saying, are we really going to have people pay for the COVID test when the government is doing it for free. Now everyone goes to private labs,” he said.

When the second wave of the pandemic hit, over 60% of all COVID tests done in Ghana were done on the infrastructure that mPharma built in the private hospitals according to Rockson.

He pointed out that before these labs were equipped, the cost of an HPV DNA test for cervical cancer was $80. This was because the samples had to be taken to South Africa for two weeks and the results sent back but today the cost of that test is $30.

The success of the $3 million molecular diagnostic fund showed that a public-private partnership could work.

Helping out with Vaccination

While still a bit reluctant to get into another public-private partnership, in November, when it became clear from different reports that the vaccination process was at risk of failing because of the lack of funding, mPharma saw another gap to be filled.

“For example, Ghana would need over $200 million to be able to vaccinate about 70% of its population and that’s just for year one. What happens if COVID becomes endemic? What if every year we need booster shots? What happens with all these new variants that are coming up,” he said.

Those were some of the questions that spurred Rockson and his team to get involved in the vaccination process.

Fortunately for mPharma, many business leaders were uncomfortable waiting for the government. The unexpected outbreak of the coronavirus meant that businesses incurred high costs in their race to keep their employees safe and productive. Some industries were more adversely affected than others; for example, factory workers weren’t able to work in large numbers anymore. And oil rig workers were forced to quarantine for two weeks before they could return to their desks.

A consortium made up of all banks, telecommunication companies, and some FMCG and oil companies in Ghana decided they would fund the vaccination of their employees.

Beyond paying for only their employees, the consortium also agreed to match the number of employees they vaccinated by giving the same number of free doses to the government.

When the first batch of doses arrived in Ghana, mPharma and the consortium agreed to give all the doses to the government for vaccinating health workers. Putting the public interest before theirs.

The bigger picture

Unlike the molecular fund which brought financial returns for mPharma, Rockson said the vaccination program was done as a contribution to society without any financial gains. He expects that mPharma would be able to build some relationships and credibility with companies and communities through this program.

For mPharma, which has a presence in eight sub-Saharan African countries, Rockson hopes that this framework which has proven to be successful in Ghana would be adopted in other countries to increase financing capacity for more vaccination.

“We need to think of how we can mobilise domestic financing in a period where several countries’ budgets are under severe strain because of the pandemic. If the government uses all its funds to buy COVID vaccines, what are they going to use to improve the education sector or to build roads?”

“We need to remember that ‘free’ is not a strategy,” he added.

While 45 African countries have received vaccines and 43 have started the vaccination process, less than 2% of Africans have been vaccinated. Compared to over 60% in other major economies, it shows that there’s still more ground to be covered. The framework mPharma has introduced might be the missing link in accelerating vaccination in Africa.