Move fast and break things is a startup motto popularized by Mark Zuckerberg, the now billionaire founder of Facebook. Mark instituted a culture of moving at breakneck speed and focusing on growth at the risk of sometimes breaking things. This mantra catapulted Facebook to huge public market success and has yielded similarly wild successes from other startups who’ve imbibed this principle. Startups like Uber and Airbnb have also added to the popular startup culture, a disdain for regulation and authority. Both companies have taken on city transport and housing departments respectively with apparent success. Like Facebook, Uber has gone to the public market valued at billions of dollars.

Health technology startups seeing this trend have started to infuse some of these Silicon Valley practices into their plans. Grow at all costs and ignore the regulators seems to be the pervading playbook. The now infamous Theranos made big news and fell spectacularly when it was revealed that its total disdain for regulation and focus on growth had put the lives of real people at risk. Other health tech startups in the U.S. recently have fallen short of regulations. Nurx, a woman’s health startup, was found to have flouted pharmaceutical regulations and risked patient safety in the way they handled medications. The San Francisco-based biotech startup uBiome had their offices raided by the FBI due to alleged sharp practices that were also inspired by a ‘growth at all costs’ focus, while Outcome Health, a “unicorn” that has raised $500 million to fund its service that puts advertising screens in physician offices also ran into some legal difficulty, and ousted founders, when the company was found to have falsified documents and overcharged customers.

Closer to home, while there haven’t been large health tech scandals to rival those in the United States, startups like Zipline, a drone startup that delivers blood and medical supplies, have recently come under scrutiny for promoting non-evidenced based services. Zipline signed a $12.5 million deal with the Ghanaian government that many commentators have argued is not cost effective or guided by proper evidence. They argue that if the same amounts were invested in comparable infrastructure that doesn’t necessarily involve drones, outcomes may be better. Innovation for innovation’s sake, they argue, while sexy, may take away resources from other more appropriate interventions.

As tech entrepreneurs increasingly turn their eyes to disrupting health, a question that arises is whether traditional startup tactics for growth and innovation are applicable to healthcare. Can one dream up an idea, create a quick prototype, charge people for it and start to scale once they think they’ve found product-market fit without recourse to much else? Can health startups ignore regulations to focus on growth or are there peculiarities to consider? What about the myriad of ethical issues that inevitably surface in healthcare?

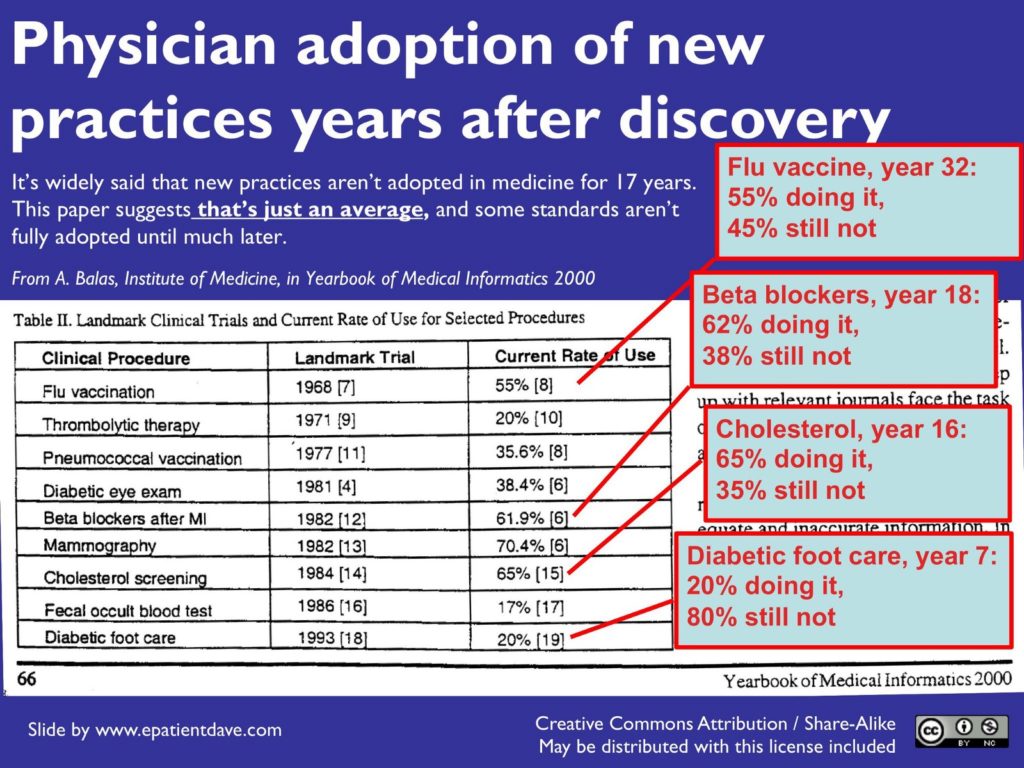

To contextualize growth in healthcare, one only needs to look at how the adoption of proven non-tech innovations has classically performed. An Institute of Medicine research study estimated that it takes on average 17 years for a proven and acceptable medical intervention to be formally adopted, and even at that, it rarely ever gets fully adopted by everyone.

In comparison, Uber went from founding to $80 billion in public market value in just over half of the average time quoted above. Evidently, the speed of change in healthcare is slow and independent of, and often beyond, the direct purview of startups. Healthcare is a conservative field where early adopter types are in the minority. This elongates the process of diffusion of change and innovation. Instead of railing against this or trying to fudge progress, startups and their investors must understand the inherent speed of healthcare and plan accordingly. Healthcare’s snail pace exists to protect patients because the number one rule of medicine is to first do no harm. Demonstrating that your startup certainly does no harm is a necessary hurdle that must be crossed by all founders.

To negotiate “first do no harm”, medicine in recent years has made research evidence pre-eminent. The field of evidence-based medicine (EBM) has soared and now guides the decisions that doctors make daily. This has led to the overturning of a lot of medical dogma as research shows inaccuracies. One such is the use of heart-slowing medications, or beta blockers, after a heart attack. Previously thought to be unorthodox, they are now a cornerstone in the care of heart attack patients.

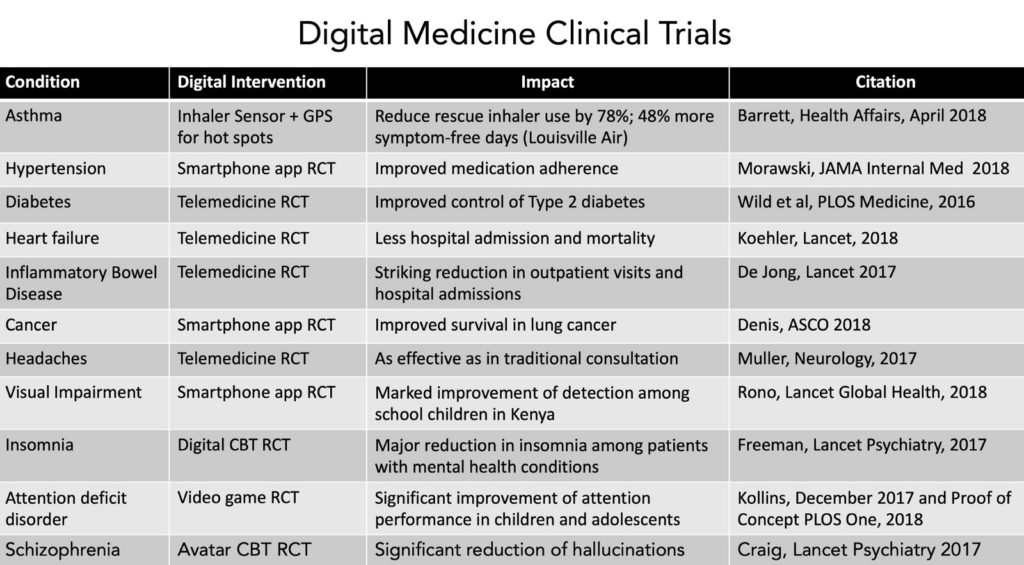

This rise of EBM means that tech entrepreneurs cannot ignore gathering evidence for the work that their startup does. The highest form of evidence favoured in EBM is a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where participants are randomly allocated into either a control or an intervention group. In an ideal setting, the researchers and the participants are blinded so that no one knows who’s getting what. At the end of the trial period, the data is analysed and the blindfolds lifted to see the effect of the intervention. Any results can then be relied upon as close enough to a true effect. Following this trend, some of digital health is beginning to move away from the fluff of its early days of near zero proof to more concrete evidence emerging.

Regulatory cover is the next thing entrepreneurs must take into account. Unlike fields such as transportation or housing, regulations cannot be taken as mere suggestions. Flouting them have real-life consequences that may include more disease, suffering and potential death, in extreme cases, for patients. In the U.S., regulators like the FDA have started to engage more with tech. They’ve begun a pilot of a digital health software precertification programme that helps to keep startups on the right side of regulations when developing solutions.

In regions across Africa, where resources may be limited, many regulators are not yet tech-savvy and much innovation goes on under the radar. Startups are thus able to get away with a lot. In fact, some pharma companies have tried to take advantage of this lax regulation in the past, getting stung afterwards.

For example, Pfizer in 1996 ran an unethical drug trial in Kano, Nigeria and eventually had to pay $75 million to settle damages 15 years later. This was a warning that even if health founders are lax in the beginning, they should still take care to err on the side of caution. Regulations that don’t exist now, may well exist in the future, and destroy businesses years down the road. Founders should implement best practice from the beginning to avoid issues later.

One area that will evidently become problematic sooner rather than later is data protection. When regulators and legislators catch up to the amount of data misuse that is happening in African health tech, things may change rapidly.

Granted, abiding by non-applicable stringent foreign regulations can be difficult and expensive. It must be said, however, that lax regulatory environments provide fertile ground for relatively cheap and fast experiments. Startups can use this to their advantage over efforts in other more advanced regulatory climes. Some have suggested that this was the attraction for the U.S. founded startup Zipline to pilot and perfect its drone technology in Rwanda.

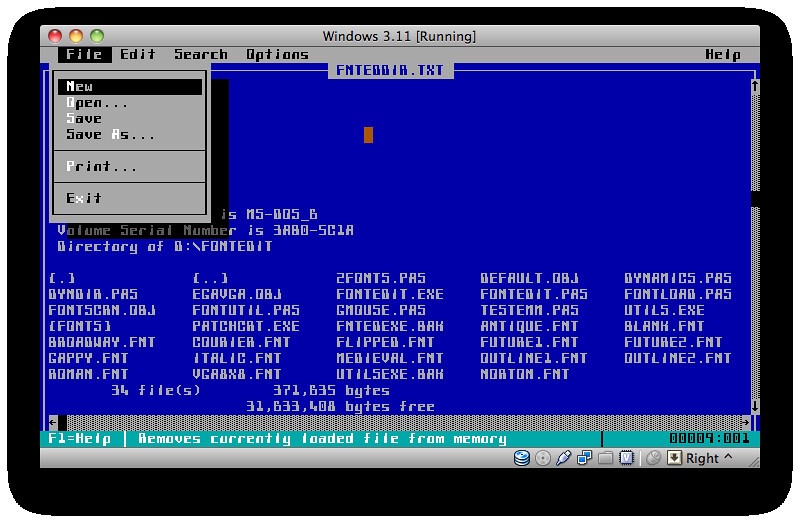

Another significant feature of the traditional startup playbook worthy of review is an appetite for providing low fidelity MVPs and pivoting at the suggestion of any stagnation. It’s thus not uncommon to see startups cycle through a series of solutions within a short period. This can be dangerous in healthcare where many practitioners are laggards, in innovation adoption terms. From my experience and that of my colleagues in multiple international health systems, many hospitals across the world are still stuck on MS-DOS interfaces in 2019.

People in healthcare are likely to request more complete products that demonstrate value for money early on before considering adoption. This puts the entrepreneur in a peculiar catch-22 of building in the dark, yet needing people to test. It takes skills to navigate this challenge. When you’re lucky enough to find an initial pilot and it doesn’t turn out well, you may consider a pivot. Healthcare people sadly don’t understand pivots the way tech people do. The paradigm in use in healthcare that approximates a pivot is the recall process for faulty healthcare products. In this instance, the response to product recalls is to be blacklisted, never to be used again. You will lose credibility if you return frequently with a different product because the last one didn’t work. Pivots must thus be negotiated slowly and with care so as not to alienate anyone or give an impression of cluelessness.

All in all, healthcare innovation is a slow, painstaking process and seeing as jail is a distinct possibility when you break things (ask Elizabeth Holmes), my advice is to go slow and steady. Contrary to popular belief that you will lose out to a faster mover, the healthcare race is not always to the swift. Slow and steady progress is how you build a true moat and win the race in healthcare.

Ikpeme Neto is the Founder at Wella Health, a digital health startup that connects individuals with pharmacies and also helps them get tested for malaria within 10 minutes. Neto is also a Founder at Digital Health Nigeria, an initiative that improves access to resources, education and capital for digital health startups, entrepreneurs and practitioners.