Olubunmi Atere moved to Kenya from Nigeria, in 2018 to pursue a degree in Marketing. Still trying to familiarise herself with her new environment, Atere would occasionally use a cab to commute from her apartment to school and back. This day had been one of such occasions. A Bolt [formerly Taxify] driver, Elias, picked her up in Upper Hill.

“He started out being polite although I grudgingly replied at first when he asked if I was okay,” Atere told TechCabal.

Keen to leave a particularly bad day behind, she let him carry on a conversation responding intermittently before finally relaxing into the ride to Muthure, which was about 40 minutes away. Until he started to give personal compliments.

“I went from trying to relax for the long ride to being alert,” Atere, who sat next to the driver in the passenger seat, said.

Seeing that she had shifted her attention from the conversation to staring out the window, the driver went quiet for a few minutes. Moments later, his hand was on her thigh and “so close to my groin,” she said. Shocked, she sternly warned him to take his hand off and was stunned when he said he thought “she wanted that”. She alighted at her destination fifteen minutes after the incident and deleted the app.

“He texted with a couple of numbers afterwards apologizing.” She didn’t report the incident to Bolt. Three previous reports had not been attended to.

A Long Ride to Safety

Before ride-hailing became big business in Africa, taxi services in cities like Lagos and Nairobi operated informally at motor parks organised by taxi unions. You most likely had to get to a park or stop one along the street, haggled until you agreed on a fare with the driver. These taxis were mostly rickety and coated in colours unique to taxis in the area. With the advent of ride-hailing services, these hassles were conveniently cut off. A taxi ride was only a tap away, in comfortable air-conditioned vehicles available round the clock. You did not have to haggle for fares and they came with the promise of safety including the assurance that drivers were carefully vetted.

But this promise of safety, it seems, is becoming even more difficult to keep as reports continue to make the rounds about riders, especially women, being harassed in various forms, from unwelcome physical contact to intimidation, verbal abuse, endangerment and in extreme cases, physical harm.

Femi Akin-Laguda, Bolt’s City Manager for Lagos, told TechCabal drivers undergo two rounds of checks before they are signed up on the service. There are compliance checks to ensure drivers’ licenses and documentation are up to date and quality checks ascertain that drivers are who they claim they are and possess skills necessary for the job.

Bolt says drivers undergo two kinds of checks before onboarding as driver-partners.

The compliance checks are a one-off, with reminders sent to driver-partners close to expiration dates so licenses can be renewed. But quality checks happen occasionally when a report is brought against a driver-partner, Akin-Laguda added.

In countries like Nigeria where centralised data collection and keeping remain a huge challenge, the results of these quality checks can be limited or unavailable. So naturally, these services come with safety nets. Riders can confirm they’re being picked up by the right drivers from the app and vice versa. In some locations, a share your trip feature allows riders share their location and trip status with select contacts. Two-way rating systems ensure that feedback is captured for drivers and riders to improve service. These tools, however, aren’t foolproof. Harassment continues to be triggered by a range of incidents, from fare disputes to cultural dispositions or sometimes nothing at all.

Cynthia Olori said she wanted to make a bank transfer to her Uber driver, William, because she had insufficient cash to cover the fare. But he refused, saying bank transfers weren’t an acceptable payment option and threatened to return her to the pickup point. Olori says she did not take his threat seriously until he “started the car and zoomed off” while adding he was going to drive her to his house. The ordeal ended when he dropped her off at an unfamiliar location at about 10:30 pm.

Violet Oyong, a multimedia journalist at The Guardian, told TechCabal many of her terrible experiences with either of the two major ride-hailing platforms in Lagos have been as a result of fare disputes, particularly with bank transfers.

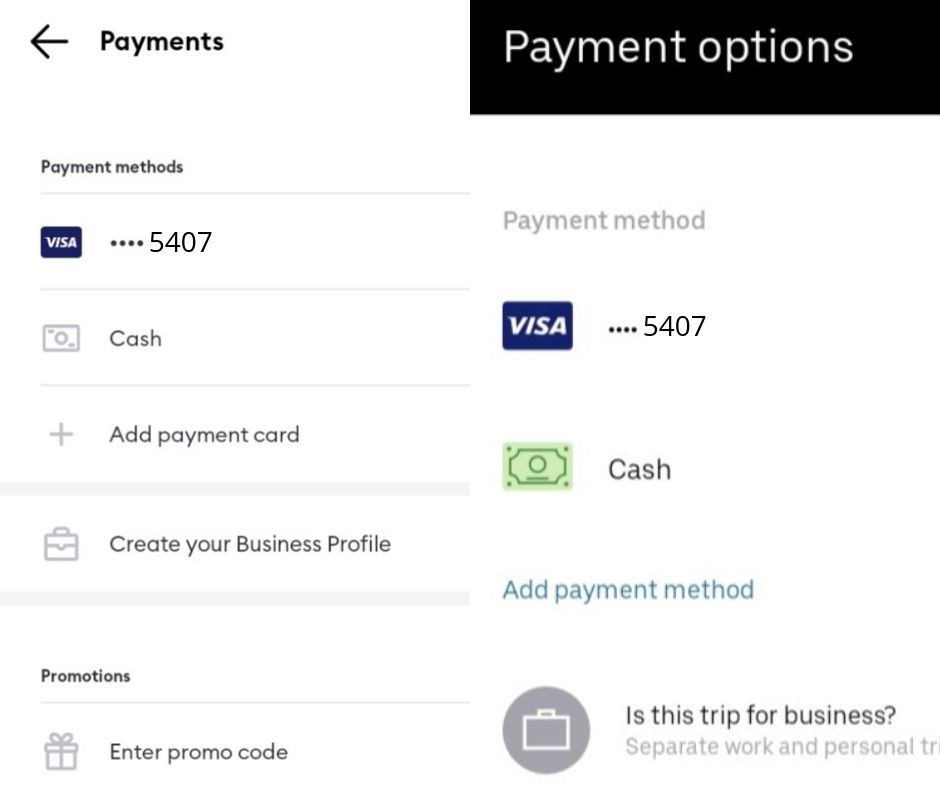

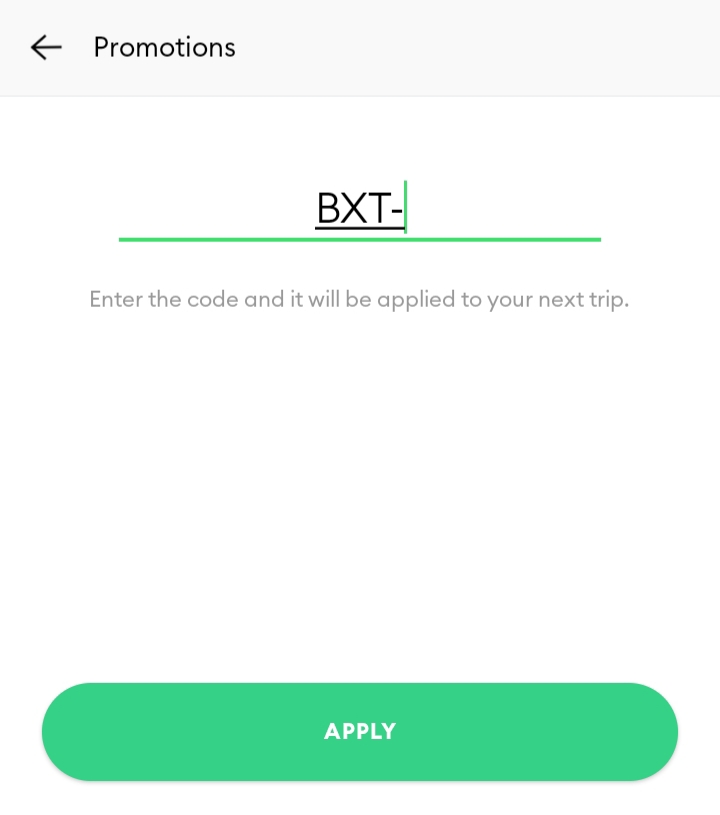

The two main ride-hailing services accept cash and in-app card payments and Bolt’s Akin-Laguda says bank transfers or similar transactions that do not occur nor are captured in-app aren’t acceptable modes of payment for a number of reasons.

Both Uber and Bolt accept cash and in-app card payments for rides.

“Not only is Bolt taken out of the transaction loop, but the process of reconciling such transactions can also take a while in ways that are unfavourable to the driver-partners.”

But it is unclear if passengers are aware of this information. Olori, who said she had been using bank transfers for two years, was told “online cash” was acceptable and was treated like any other cash transaction between riders and driver-partners after she reported the incident to Uber.

A Gender Divide?

While women are more at the receiving end of these incidents by predominantly male drivers, it seems men aren’t spared either. MJ, a graphic designer, shared an experience similar to Olori’s he had while riding from Maryland on the Lagos mainland to Magboro on the outskirts of Lagos. This time, the Bolt driver made good his threat driving him back to his pickup point whilst a heated exchange went on at about 1 am. It is safe to assume that given the location and time of day, the driver may have been worried about his own safety for good reason.

In 2017, an Uber driver was allegedly strangled and his vehicle stolen and transported to another state for sale. And although the details remain unclear, a then Taxify driver, Olumide Salami, was murdered in January reportedly while on a trip with armed bandits posing as passengers. To foster driver security, Bolt launched an SOS button for their driver-partners for “security and health emergencies.” Uber also launched a similar feature, the driver emergency button, for its driver-partners. Riders, however, are still left with in-app complaints feature that can only be used after a trip has been completed.

“It isn’t that there is a preference for driver security,” says Akin-Laguda. Drivers must have their phones while working hence making it possible to send out an SOS without fail, in emergency situations, he argues.

Women have it worse still. In culturally conservative societies with subversive gender roles, sitting in the proverbial owner’s corner in a car or giving instructions to a driver-partner who is male can easily be interpreted as demeaning or rude. As can heading home late at night be interpreted as being loose and irresponsible. Whatever the case, being threatened to be dropped off in a deserted location at night without an option to immediately report the incident remains a big safety loophole especially for female riders.

Here’s a Voucher for Another (Sour) Trip

According to Atere, one of the times she did report being dropped off abruptly by a Bolt driver in Nairobi around midnight, she was offered an “apology voucher” for another trip. Timi, whose incident with a Bolt driver had resulted in a physical altercation, says she was also offered a voucher after she complained about being harassed by a driver-partner. Uber added Olori’s fare estimate for the trip to her Uber credits to use on subsequent rides. But offering apology vouchers as an atonement for unwanted physical contact or endangerment is at the very least, insensitive not just to the riders who have reported the incident but for subsequent riders whose requests said driver would accept.

Bolt says it does not offer vouchers for harassment cases.

“We offer vouchers for minor situations, like complaints about price discrepancies resulting from GPS errors,” says Akin-Laguda, adding that vouchers are never sent to riders as compensation for confirmed harassment cases.

When riders bring a complaint against a driver-partner, Akin-Laguda says, the company investigates from the perspective of the rider and the driver-partner. A high-priority team, which handles all reports of harassment always refers the rider to report any criminal incident to law enforcement.

“We support with every information regarding the incident available to us and necessary to help the case.”

Depending on the degree of a non-criminal misdemeanour, Akin-Laguda says the company responds in a number of ways including temporarily halting a driver’s operations to allow them undergo specific re-training to improve their service delivery.

Uber did not respond to multiple requests for comments at the time of publishing this story.

Atere rarely uses either of the two services “because they’re the same”. But a lot of times, she has no choice. Most times, when she can, she rides with someone. And while she is yet to make it a duty to seat behind the driver as the services urges passengers to do, she is always guarded when taking a trip in an Uber or a Bolt.