Microlending platform FairMoney offers small loans of between N1,500 – N150,000 to Nigerian with maturities of 1-3 months. To determine who is fit to receive a loan or not, an algorithm allows the company evaluate an individual’s creditworthiness using two parameters: financial data and alternative data. With financial data, the algorithm evaluates the ability of the individual to repay what he has borrowed, how much is fit to lend to them, and with alternative data, the algorithm evaluates the readiness of the customer to repay.

“Does he use piggybank to save money, does he read the national press? We are looking for indicators to tell us what the customer’s financial standing looks like and to what extent we want to lend to the customer and how much,” says Laurin Hainy, CEO, FairMoney.

At the moment defaults on loan repayments are around 10%, he said. FairMoney currently has a customer base of 200,000 and is hoping to expand its services since closing a USD$11 million Series A round.

Interest rates in Nigeria are relatively high. One reason for this is the Central Bank’s benchmark interest rate, the monetary policy rate (MPR) which currently stands at 13.5%. While most commercial banks lend at between 20-21%, sectoral implications mean that lending rates can go as high as 30% or more. Fintech startups like FairMoney have become attractive because of the lower interest rates they promise.

“Generally, what I’ve seen in Nigeria, particularly when we started, the business model of the bank will be to take deposits of the population and basically shift this portfolio to larger companies of the state,” says Hainy.

“And most commercial banks are like this. Nigerian banks are not the best comparison for pricing point because they also do not like to take a lot of risks.”

For him, loans given to large accounts with 2-3 year maturities cannot compare with 1-month loans given to one man businesses as the risks are not similar.

“I look at my product to know, are we competitive? Do we propose the right pricing? I’m looking more at peers in terms of pricing and in terms of general loan products.”

Lending platforms like Carbon and Renmoney offer rates between 4-15%. Aella Credit offers rates between 4% to 29%. Rates often vary depending on the maximum amount each lender offers.

Hainy agrees that these lending rates can be high depending on who you compare them with. However, the major rivalry is the loss rate which overall in the market, is somewhere at 10%.

“I’m quite confident that as the ecosystem develops, and as the credit system is improving, over time that the loss rates will decrease and the pricing improves.”

If this happens later than sooner, there is a chance that apps like FairMoney’s may no longer be available for download. Google recently announced plans to ban lending platforms that offered 60 day maturities or less to their customers.

“We didn’t develop 30, 60 or 90 day long maturities because that’s what the customer needs,” says Hainy.

“We ask customers how long they want to borrow and it so turns out that the majority of customers prefer short maturities often because of the use cases for which they take the loans in the first place—small businesses, very small businesses.”

“Our concern is developing lending products that the customers want to use.”

The idea that Google decides maturities for a customer in Nigeria isn’t ideal, he says adding that they have shared their opinions with the people responsible for the policy and the company is looking forward to how this plays out. But he is confident that a company like Google understands the differences in the ecosystems in Nigeria and the rest of the world and will act accordingly.

The idea behind the move, as Google said, was to curb predatory lending which is a term for loan practices that are exploitative to customers. The number of fintech services offering micro credit has increased sharply in recent times. But still, has this become predatory in Nigeria?

“What happens in the US a lot is that companies would charge non-transparent rates so that when the customer takes up the loan he actually does not know how much he has to repay. And then when he has to repay, he realises he has to pay double the price,” says Hainy.

According to his observations, this lack of transparency, especially with interest rates and loan repayments isn’t present in the Nigerian market.

“I can’t speak for others, but if our customers cannot pay, we don’t re-lend to the client and we just lose our money. We have absolutely no interest to offer loans that customers cannot afford.”

FairMoney’s Series A funding round was led by a social impact investor, Omidyar Network through its fintech ventures arm Flourish, whom Hainy says would not have come on board if they did not think how FairMoney’s products are designed is deeply in the interest of the customer.

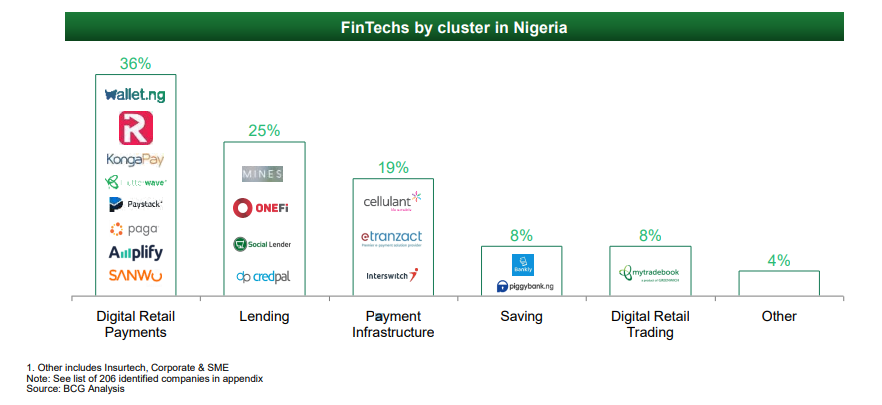

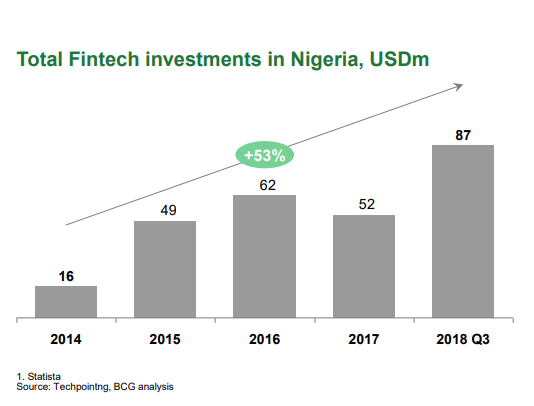

Source: EFinA Fintech Report

The fintech sector in Nigeria and across Africa has grown rapidly and seen a significant uptake of venture funding. Customers now have a wide range of payments, lending, wealth management services to choose from and more. But in spite of this, individuals at the bottom of the pyramid are still hard to reach and you find these startups serving the same demography. Laurin says what stands FairMoney apart is its vision to offer reliable and less expensive credit to Nigerians. Ultimately, the company is slowly building its own digital bank and plans to obtain a microfinance license from the Central Bank. The bank will ensure that customers can access loans easily, say goodbye to hidden maintenance and issuance fees and carry out bank transfers for free.

“Already we are offering payments, value-added payments, and these are services we just offer to have customers keep using our services.”

To reach more last-mile user, FairMoney is also building USSD solutions for localities and areas where smartphone penetration is still low.

After Nigeria, where next?

“There are indeed many more markets like Nigeria where similar problems and dynamics are in place” but Laurin says the company is staying focused at this time on the Nigerian market.