In Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, 40,000 phones are sold every month.

The city is home to 13% of the country’s 85 million people. Unsurprisingly, it is the country’s rallying point for entrepreneurship.

While possessing a mobile phone is considered a normal thing, smartphone penetration is still fairly novel owing to low broadband availability. As of 2015, only 3% of the country had 3G connection according to a GSMA report.

Thanks to digital finance initiatives from big banks like Ecobank and UBA, financial inclusion has grown to 26% in recent times. Vodacom Congo, Orange RDC and Bharti Airtel are among the leading providers of mobile communications to between 35 and 40 million subscribers.

These are not great numbers. Indeed, the DRC should be doing better with its material and human resources. It is the second largest African country by land area, the fourth most populous, and 60% of Congolese are between the ages of 15 and 25.

In the 21st century, they are not showing up much on the African tech conversation.

While it is exciting to see global acclaim for startups in North, South, East and West Africa, a representative view of innovation in Africa must engage slower growing places like the DRC.

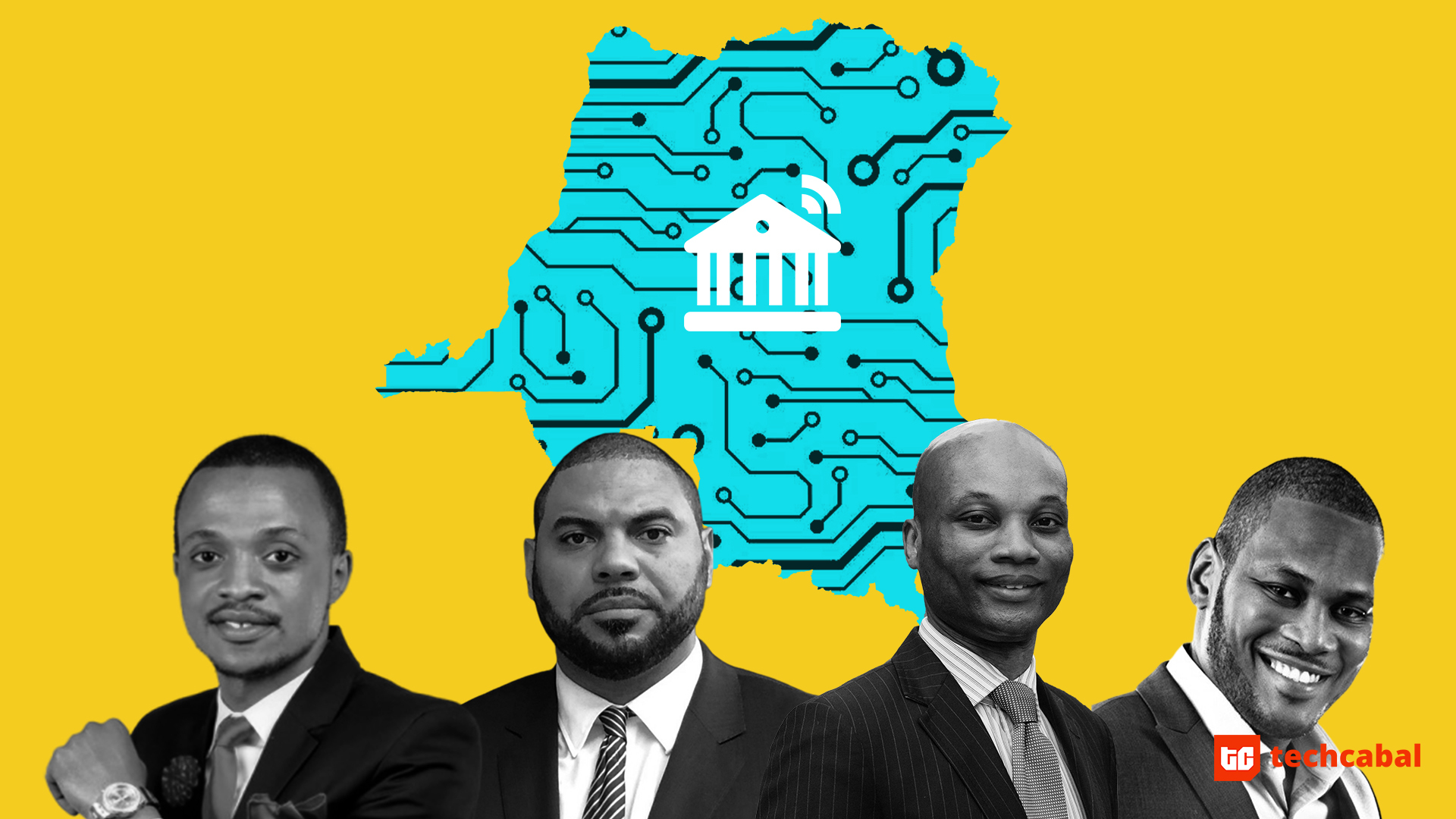

Under the aegis of the Congo Business Network, a group of entrepreneurs from the country are doing that.

Though born in the DRC, Noel Tshiani has now been in the US for 24 years. A former military officer, Tshani founded an advisory company to advise businesses on strategy.

But after realising the difficulty in running businesses in his home country, he began the Business Network as a platform to amplify and help guide local entrepreneurs for global visibility.

By attending events like the Africa Tech Summit, the Network hopes to tell an alternative story about the DRC as a country enthusiastic about the possibilities of technology. The trips are necessary as many of the country’s bright minds tend to migrate early for education and professional careers.

Ruddy Mukwanu has lived in South Africa for 18 years. He goes back to Congo from time to time to oversee that side of MaxiCash, a startup he founded in 2016.

MaxiCash provides a platform to enable remittances and electronic payments, giving the unbanked an introduction to financial services.

Instead of opening individual accounts with multiple mobile money operators, MaxiCash gives the user a Visa Card with which one can accept all payments including from banks.

Fintechs pushing the innovation needle have had to withstand initial skepticism and aversion from banks and telcos, Mukwanu says, but relations are improving.

“Most of our startups are now working much closely with banks to develop products together,” he says, though a high capital barrier for entry in the financial services space preserves the banks’ dominance.

At the moment, the biggest platform for collaboration between key actors in the DRC’s financial services industry is Multipay Congo launched in 2015.

It is the DRC’s first inter-banking platform enabling interconnectivity between bank transactions. Created through a collaboration of Banque Commerciale du Congo, FBN Bank, ProCredit Bank and RawBank, the platform plays a settlement role that creates co-existence between payment platforms like ATMs and point of sale machines.

“We really hope that we can start interconnecting,” says Djo Moupoundo, another one of the group of Congolese that cut their professional cloth outside the country’s shores.

Moupoundo’s client acquisition company helps DRC banks onboard clients. With over a decade’s experience in the country’s financial sector, he would like to see more interconnection at lower levels.

“Interoperability is what will create the ecosystem. DRC is huge and there is room for everybody,” he says.

Of course not everyone in the DRC experiences financial services in the same way. The country is one of the poorest in the world with more than 70% living on less than $1.90 as of 2018.

In Goma where Faysal Axam is based, low internet quality affects smartphone adoption. His startup, the Faysal Company, has a Tap and Pay electronic payment system for smartphones, but it is his USSD feature that gets traction.

Thanks to Tecno feature phones – which retail at about $20 – people in that Eastern region of the country can access mobile money platforms. But it is not enough, and Axam would want the government to improve internet connectivity in the country to enable people outside of Kinshasa benefit from the promise of digitization.

It would have been great if they didn’t have to wait for the government. In Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa, startups are leveraging local and international venture funding sources for disruptive innovation.

But because the DRC ecosystem is barely two years old, there’s little significant investment going into startups. Startups that emerged in the last couple of years have only started to gain visibility.

There are practically no venture capital firms dedicated to funding startups in the country. Even if a firm were interested in funding a startup with, say, $5 million, there are no metrics or data on which to evaluate how reasonable a deal it would be for both investor and the company.

Tshiani wants to use the network as a medium for propelling startups to global platforms where interactions can produce investment

If it’s any consolation, neither Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa nor Egypt are in any way developed tech nations. Each has aspects of its climate that remain stumbling blocks to rapid growth.

Yet, Moupoundou has no illusions as to the work they need to do in the DRC to catch up. “We still need to prove ourselves. Some of our startups are still scratching the surface.”