Small and medium businesses across Africa often have a hard time getting loans; OZÉ, a Ghana-based fintech startup, wants to change that.

In Nigeria, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) account for 96% of businesses and 84% of employment. They also contribute 46% to Nigeria’s gross domestic product (GDP).

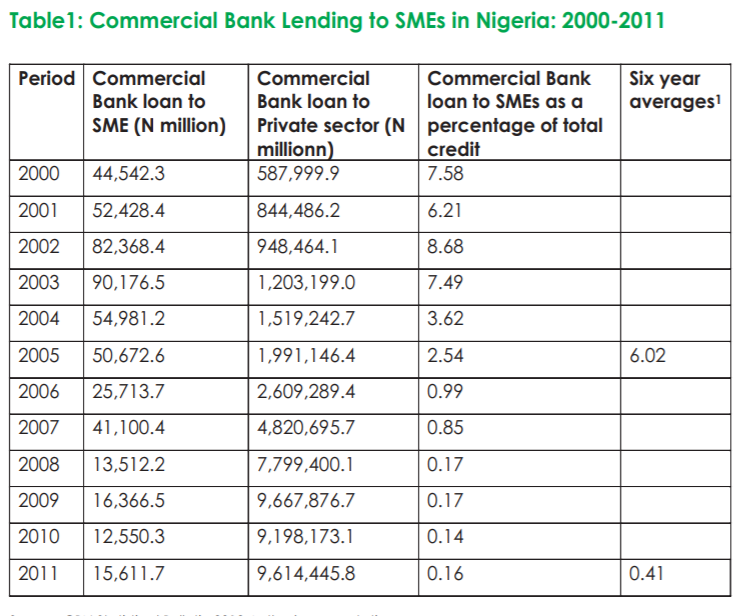

If SMEs succeed, Nigeria’s economy will be better for it. Yet, one key determinant for success, access to credit, is still a big problem.

“According to the Banking and Other Financial Institutions Act(BOFIA), the Nigerian government, and by extension CBN, have mandated banks and other lenders to ensure loans have to be securitized by any form of collateral.

“This is why banks ask for your mother’s blood before giving you a loan.”

–Can we build a credit culture in Nigeria?”

In Nigeria and most parts of Africa, most banks lend to larger corporate players and more established companies. While there is a broader lending problem in Africa, SMEs have a specific challenge. They are often unable to provide the data that banks need to assess risk effectively.

According to the London Stock Exchange Advisory Group, “banks are likely to use sophisticated scoring models when assessing creditworthiness. But SMEs often lack the track record and meaningful data inputs required.”

One African startup, OZÉ (pronounced oh-zay), wants to change this. OZÉ helps SMEs track the data that matters. It then connects them to the financial institutions that can give them loans.

OZÉ’s Francophone roots

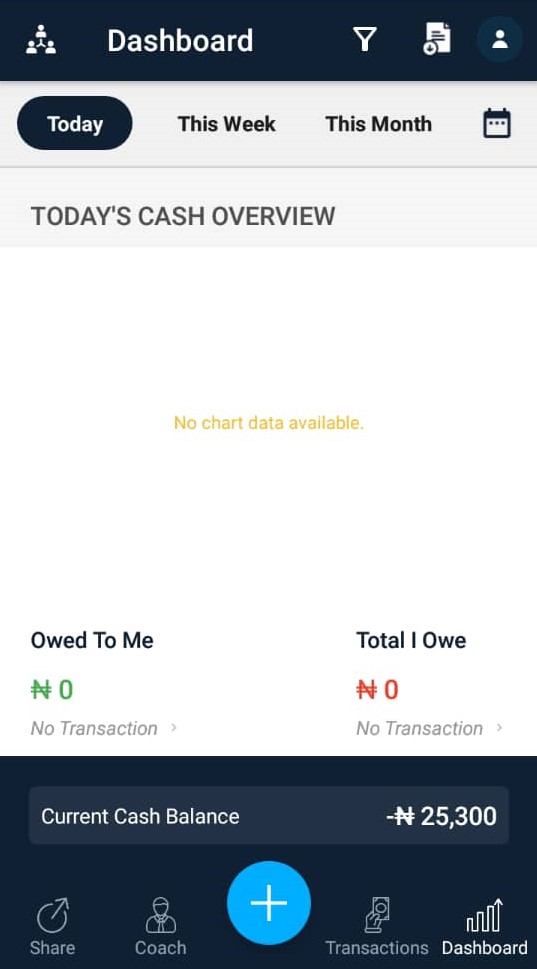

OZÉ is an app that helps business owners track when money is coming in and leaving, all on the go. The app uses the information you provide real-time updates and alerts about your business’s health.

It’s a habit-forming app that incentivizes SMEs to track meaningful business data that they can then use to access credit.

Meghan McCormick, OZÉ’s co-founder, and CEO told TechCabal that the startup was founded in Guinea and came out of “Oser innover.” . Oser innover is a business accelerator and is French for “dare to innovate.”

Meghan says, “we didn’t want it to belong to the Francophone countries or Anglophone countries, so we spelled “oser” wrong on purpose.”

At the heart of OZÉ is the idea that small business owners need all the support they can get. It first began as an offline solution but Guinea’s Ebola epidemic forced the startup to think about supporting SMEs remotely.

“We asked ourselves, how do we support SMEs to grow and succeed in a difficult market with analog management tools? We figured that there has to be a better way, so we started building.”

The prototype of the OZÉ rolled out in Guinea. But the founders saw that the app’s prospective users didn’t even have internet access. This discovery was their cue to look at new markets.

The Pan-African play begins with Ghana and Nigeria.

Even though OZÉ is translating the app to French and has plans to launch in other Francophone countries, Meghan’s thinking is that the region’s addressable market is small.

The company took the prototype app to Ghana in 2018. The Ghana pre-launch was a great choice. Ghana has the highest mobile penetration in West Africa.

Yet, the critical question was whether people would share their financial data, which the app requires, with strangers. They also needed to figure out the right incentives to give people to share this data.

“At the beginning, we had 36 entrepreneurs on the app, and every day, the data would come in. I would stay up at night, turn it into a dashboard in PowerPoint and make it into the width of a phone. I would then send it as a PDF file to entrepreneurs on Whatsapp.”

OZÉ is now ready to push its refined product across Africa, with Nigeria as their first destination. The startup received $700,000 in seed funding from Anorak Ventures and Matuca Sarl to fund its expansion. Angel groups like Nigeria’s Rising Tide Africa joined existing investors, Ingressive Capital, and MEST in the seed round.

Although Nigeria is a notoriously tough market, OZÉ believes that the country is so competitive. This competitiveness is why business owners often try to find something to give them an edge. OZÉ wants to be that edge.

The addressable market for OZÉ

A recent TechCabal report asked, “What’s next for Wave’s African users after its exit?“ That answer might be OZÉ.

Like Wave, the OZÉ app allows users to send invoices and receipts. With the complaints that greeted Wave’s exit, there’s no doubt that those two features drove its popularity. Wave’s popularity in Nigeria suggests that there is an addressable market for OZÉ.

Nonetheless, OZÉ made it clear that the company has no plans to solve the lack of access to accounting tools.

“I see a lot of people trying to copy QuickBooks for Africa and Wave for Africa. I knew that wasn’t going to be successful. So we stepped back and said, ‘what do we really care about?’”

The app wants to help small business owners know how they are performing. Without this knowledge, business owners make decisions based on intuition rather than data. That’s risky when you’re a young business owner with no experience in a challenging market.

“For instance, once you know you’re selling your product at a negative profit margin, you either have to raise your prices, lower your costs or discontinue that product.”

These insights would be useful to an increasing section of Nigerian entrepreneurs using social media as a marketplace. With companies like Flutterwave creating virtual storefronts for social commerce, the savviest business owners will seek an edge.

These are compelling reasons to use the app, but OZÉ’s real game-changer might be the access to financing that it provides.

Using business data to provide access to financing

Although OZÉ did not start out providing access to loans, it now offers its users that opportunity thanks to its partnership with banks.

The startup says that it uses its “proprietary algorithm” to look at user data and then connect them to the financial institution responsible for giving out loans.

It says that although its loan portfolio is small, it has recorded no defaults to date. Most of this is because, at the core, OZÉ’s lending add-on works a lot like the original idea of microfinance banks popularised by Prof. Yunus’s Grameen bank.

By collecting the invoices, receipts, and transaction history of a business, it is easy to develop a loan size that matches its profile. Also, users have to use the app for 90 days to become eligible for loans. Despite the value that access to credit adds to the app, OZÉ insists that the use case for keeping track of business data is more than loans.

“There’s so much money to be made by getting your operations under control, and tracking your data plays a large part.”

Some people might point out that businesses can fake some of this data in hopes of receiving a loan. If this happens, OZÉ quickly verifies this information by checking transactions against bank and mobile money statements.

One of OZÉ’s competitors is Lidya, a startup that counts Nigeria as one of its markets. Lidya’s financing process is faster, needing SMEs to only share their bank statements with a promise of a loan “within twenty-four hours.”

OZÉ also has to compete with Microfinance banks (MFB). Although only a handful of MFBs are online, they are arguably closer to the addressable market and market to them in person. In Nigeria, where loans are sometimes relational, the marketing approach of MFBs work.

OZÉ will also find itself competing with some of Nigeria’s big banks that are ramping up lending after a CBN policy increased the lending to deposit ratio. It has forced big banks to diversify their loan offerings. A few of these banks are now marketing their SME loan offering, with Access Bank claiming in 2019 that it gave ₦37 billion in loans to SMEs. Nonetheless, it feels too early to know how much impact banks have made in SME lending since the LDR surfaced.

The revenue angle

OZÉ uses a freemium model with basic features available for free. The tiered versions, which give you access to analytics and figures, start from $2 (₦790) per month and go up to $20 (₦7,890).

Another way the startup makes money is with its auxiliary product called OZÉ Enterprise, which helps nonprofit organisations to track the impact of their training and programmes.

It also makes money from its lending business by collecting a commission when users receive loans from financiers. In terms of its revenue mix, the startup wants to make more money from the app than its commission from loans.

“If most of our revenue comes from the app, it allows us to focus on giving users the best experience. If we come to a point where most of our revenue comes from fees from the bank or the nonprofit organisations, those are now our customers, and the small businesses become the products. We never want to get to that place.”

It means that they’ll be counting on getting users to pay for subscriptions. The early signs are promising because, like most habit-forming apps, it can become sticky once people use it for a period.

It also helps the app’s stickiness in integrating with Payment Service Providers (PSP) and ensures that people can send and receive funds within the app. This strategy looks a bit like what other fintech apps are doing, hone in on a core focus, but provide some basic banking features that increase engagement.