The full impact of COVID-19 may not be known for decades to come. But in many instances, the changes are already with us. One is a digital platform connecting victims and survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in Nigeria with agencies capable of providing help in various ways, including legal and psychological – all thanks to three dedicated activists.

[This story was provided to bird by Storify, an agency under Africa No Filter]

By Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu / Africa No Filter

In 2019, Khadijah Awwal, Khalil Halilu, Olajide Abiose and Khadijah Awwal began developing a solution for a burning issue for victims of sexual violence – how to report cases with as little hassle and bureaucracy as possible. Working with the Center for Civic Citizen Welfare and Community Development in Africa (CWCDA), they decided that a digital solution was the way to go.

“It’s always been on my mind,” Awwal explained, “because I’ve witnessed all sorts of gender-based violence cases over the years.”

While many other organizations were doing similar work at the time, there didn’t seem to be any kind of progress. Under the CWCDA’s watch, Halilu, a leading voice in the tech space, Abiose, a civil rights executive and Awwal, a lawyer and founding member of NorthNormal (an advocacy group working in the sexual and gender-based violence, or SGBV space) got work.

Then, COVID-19 hit. And with lockdown came a wave of sexual violence reports.

“We know that the situation was bad. But the COVID period amplified the situation; it made it very obvious how bad things were. This was a pandemic within a pandemic… A lot of women were stuck with their abusers at home…So we just worked hard on a digital solution,” Awwal explained. One of the events that made people even more determined to find solutions happened at the height of COVID-19.

On May 27, 2020, with the pandemic peaking worldwide, 22-year-old Uwaila Omozuwa, a first-year microbiology student at the University of Benin (UNIBEN), made her way to a church in Benin, southern Nigeria, to study. Uwa sought out the Christian parish for the peace and quiet it provided – and to feel safe.

About an hour into her study, Uwa was attacked by three men. She was raped, her head was bashed in with a fire extinguisher, and she was killed.

Omozuwa’s story sparked national outrage and birthed the hashtag #JusticeforUwa. Activists organised protests in major cities, demanding justice. They were fighting for justice, not only for Uwa, but for many other victims of sexual violence, including Tina Ezekwe and Ochanya Elizabeth Ogbanje, who also became rallying points, after they were attacked.

According to reports, there were about 3,600 reported cases of rape during the lockdown in Nigeria, which lasted a total of 73 days. This figure is considered by those who work in this field as grossly inadequate. A staggering number of rape cases never go reported in Nigeria. A more efficient reporting system may have seen Uwa’s killers apprehended prior to her killing

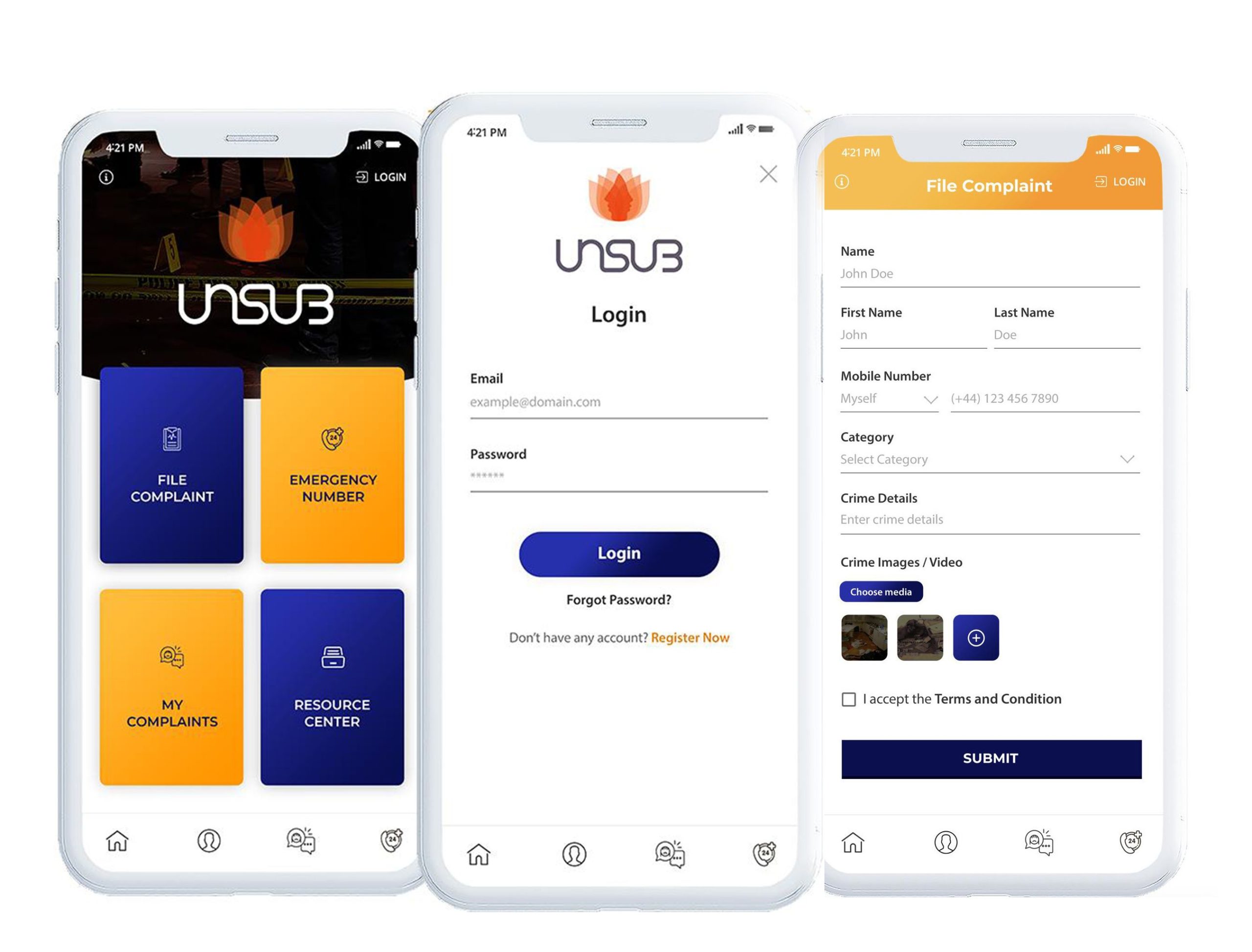

Motivated to see a solution, the 3-person team designed a digital platform which they called UNSUB. The platform works both as a mobile and web application, connecting the victims and survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in Nigeria, with agencies working in the field.

The app provides help in various ways, including offering legal aid and psychological support. The app also uses the location of the user to recommend agencies near to the victim to ensure that help reaches the complainant as fast as possible.

“The app connects users with people working in the SGBV-response space within their location to access the intervention needed while ensuring the confidentiality of such reported cases on the platform,” Khadijah Awwal says.

“With the spike in SGBV cases in Nigeria, which could be attributed to the nationwide lockdown that was implemented to combat the continued spread of the virus, it became imminent for us to roll out UNSUB as a contribution to the fight against SGBV in Nigeria,” Grace Peter, the communications officer, says.

Additionally, the app allows concerned third parties to report violence cases on behalf of other people.

The man who found Uwa lying in her pool of blood in the church that day, for example, would have been able to report the incident on her behalf as a third party.

“The providers/stakeholders already working within the SGBV-response signed up to provide different categories of interventions/support on the UNSUB platform, all within a timeframe that ensures cases are handled more efficiently, effectively, and timeously through the use of technology,” says Grace Peter.

UNSUB has been in the works since 2019, and the group has been engaged in thorough research to understand how it could be most suited to tackle the SGBV menace in the country. Khadija Awwal, a founding member, explains that the rise of cases during the lockdown was one of the central motivations for developing the App.

They also observed that many SGBV cases in Nigeria were left unattended as “many survivors never see the justice they seek due to bureaucracies involved in the current reporting system.”

Impact on users

Some survivors were left at the mercy of their assaulters without receiving an intervention. The impact of COVID-19 measures, such as lockdowns and restriction of movements, meant that some stakeholders were unable to identify, assist and follow up on the survivors, Grace Peter explained.

Aisha* says she once used the app to report a case of sexual abuse and seek help with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which she had developed due to sexual abuse she experienced from a family member.

She had heard of the app through a journalist-friend who encouraged her to seek help. Aisha filed a complaint through the website. She used the mobile app, which popped up a form to fill in with her name and contact details. The form also required her to specify whether she was making a complaint for herself or on behalf of another person.

After filling out the form, she clicked ‘submit.’

A few days later, a mental health organization reached out to her and assigned her a counselor.

“We had some sessions through phone calls and Zoom, and it really helped,” Aisha remembers. “And therapy is very expensive in Nigeria. This organization did it for free for me.”

She explains that even though her therapy has since ended, the counsellor occasionally reaches out to check on her. According to Khadijah Awwal, this is very critical to their work with UNSUB.

There are about 170 agencies, and platforms signed up on the platform. This includes government agencies and CSOs. Currently, the app has around 400 cases at different stages of intervention.

Awwal explained that the process of getting organizations onboard the app is a thorough yet simple one.

“As an organization or a government agency, you sign up on the platform with your platform’s kind of intervention. It could be psycho-social support, it could be medical support, or it could be shelter,” she said.

“So you sign up, stating clearly what you can provide, with your location. Once you sign up, the admin vets you to see if you’re fit to be part of the platform. Once you’re accepted, you’re a stakeholder on the platform.”

Before this, there were instances of the duplicity of functions among stakeholders, leading to inefficient performance and outcomes and diversion of resources towards other effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The number of reports recorded was overwhelming during the first few days after the app launched, according to Awwal, with many of the cases reported being of police brutality. The team is now working on another solution capable of dealing specifically with reports of police violence.

While the mobile app is filling a wide gap in the SGBV response rate in Nigeria, there is room for improvement.

“A number of stakeholders do not feed back much info into the app unless they are being prompted by members of our team to do so,” Awwal said. This affects efficiency.

Also, as the app can only be accessed using a smart device and an internet connection, almost half the population remains unserved. Nevertheless, digital solutions are important to curb the problem, especially in this time and age, said Hassana Maina, a lawyer and SGBV activist in Nigeria.

“UNSUB and other digital solutions to sexual and gender-based violence cases are important to curbing sexual violence because we live in a digital world.

“It’s highly important for victims, but also for institutions especially for preserving data. It’s also useful when partnered with the criminal justice system because the police can always find it a great resource … Overall, when it comes to the protection of women, no stone should be left unturned,” Maina said.

Despite the challenges, UNSUB provides a unique and increasingly important link between victims/survivors of SGBV like Aisha and the help and support they need to overcome their ordeal. It also shows what can be done, locally, with limited resources, to provide help to those affected.