It is exactly 1 year, 6 months and 10 days since the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) became operational in 2021, yet intra-African trade is neither free nor continental. There is some history behind this and a lesson for policymakers and the new crop of tech-enabled enterprises foraging in the cross-border logistics space.

The roots of African trade

The Sahara was once an important route for travel in Africa. It carried salt and gold north to the Mediterranean and brought back cloth, pottery, horses, ornamental weapons, and religion. Goods from sub-Saharan Africa reached Europe through the desert long before Europeans set foot on the mineral-rich soils south of the Sahara, and for centuries. This south-west-to-north route and the corresponding flow of trade which reached as far south as the Akan forests in present-day Ghana, and extended eastward as far as Ngarzamgu in present-day Nigeria, helped define mediaeval Africa as the land of gold, created bustling markets and a professional class of rich tradesmen, and spawned empires.

While central Africa was relatively isolated, trade along the Swahili coast flourished on the eastern flank of the continent, supplied by goods from the Zimbabwe plateau that fed markets across the Persian Gulf and as far as India. Southern Africa was not left out as Khoi pastoralists and other Bantu-speaking peoples formed intricate trade networks from Batswana in the north to the southwestern tip of the continent.

Some of these trading networks became the beachhead from which Portuguese traders, and later much of Western Europe, inserted themselves into and, eventually, reshaped African trade to fit European industrial input requirements.

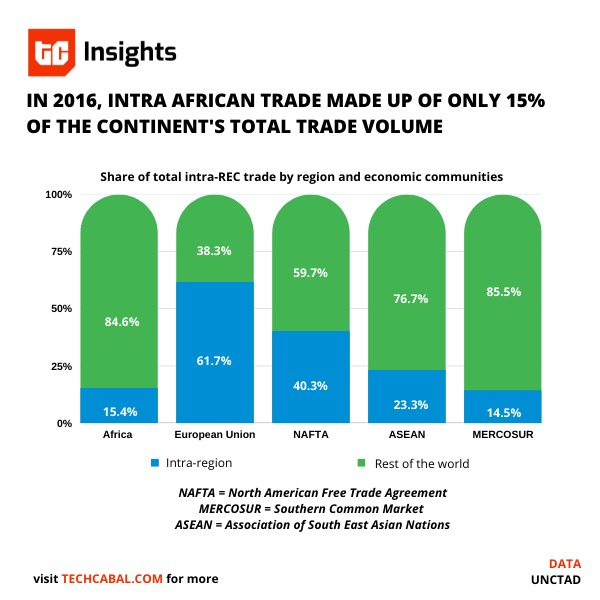

The point of this history jaunt is that trade is not a novel concept in Africa. Africans are well versed in regional trade and had, for centuries, operated regulated trade networks that covered vast inland distances. The next obvious point is that sometime in the last 2 centuries, this began to change as African states fell into decay, ultimately succumbing to colonial forces and, later, poor post-independence leadership. The result is the montage of structural defects we have today that prevent any meaningful trade integration, regional or continental.

Reread that last sentence. The structural defects of trade in Africa mean that even regional trade integration is an uphill task, to say nothing of building a continent-wide market. One quick example to illustrate why.

In 2013, the East African Community launched a single customs territory to simplify trade between member states and cut shipping costs by clearing shipments at their first port of arrival or departure. However, if you needed to send a consignment of goods from the port at Mombasa, Kenya to Byumba in Rwanda, you would have to physically submit scads of documents—shipping records, invoices, permits, certificates etc.—to customs authorities in Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda, the three countries where the consignment will pass through.

In the West, trade between countries in the Economic Community of West African States is routinely interrupted by closed borders, bizarre import substitution policies, and occasional scuffles between foreign entrepreneurs and law enforcement. Of course, in most cases, these products are imported from outside Africa, but that is beside the point, which is simply that buying, selling and, importantly, moving goods within Africa is a headache we have lived with for too long.

All of this is the background setting for the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement

Partner Message

Build better customer relationships and improve sales conversion with Simpu. Unify all communication channels like emails, WhatsApp, Twitter DMs, Facebook Messenger, SMS, and website Livechat into one place. Unify your inbox with Simpu for free

Not a single market

The problem is that although the AfCFTA is new and carries so much promise, it still faces the same old problem. Namely, Africa is not one entity by any measure.

Existing regional trade agreements are exclusive and differ wildly from trade agreements elsewhere on the continent. These regional agreements are themselves frequently ignored in favour of national protectionist policies like Kenya’s recent ban on Ugandan eggs, or petty political disagreements

Source: Boluwatife Sanwo/TC Insights

Where countries are relatively more open to cross-border trade, poor infrastructure and non-committal governments combine to frustrate the free flow of goods and services. Take the 1,028 km highway planned between Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire. Construction for Nigeria’s section, the 66 km Lagos–Badagry Expressway, started in 2020. But so far, only 17 km of the road has been completed.

Among other reasons why the AfCFTA is struggling, these 2 uncomfortable facts stand out. First, is the unresolved confusion of building a single continental market within which several dysfunctional regional markets already compete. And second, is the abysmal infrastructure that slows down the movement of any good that needs to be delivered across a border to a crawl.

“There is no need for another conference, summit or, put plainly, photo op to smoothen the wrinkles with AfCFTA as it exists. Governments only need to do their job—and in the absence of camera lights.”

But several companies are trying to make the best of the circumstances. Alongside older conglomerates like Bolloré Africa Logistics, newer players sporting shiny digital tools want to rebuild cross-border trade in Africa. While they have no influence over production and even less with trade policy, these firms are already deploying technology to manage freight, paperwork, and even offer vendor financing.

But they can only go so far.

Camel caravans and empires: the lesson from ancient trade

Alongside asset-heavy freight handlers and shipping companies, digital freight management firms like Ghana’s JetstreamAfrica or Nigeria’s OnePort365 can function like the camel caravans that transported gold and salt across the vast dryness of the Sahara.

And like those caravans, a privately owned and operated corps of tradesmen is vital to operating the supply chain part of a functioning trade network. But even camel caravans could no longer traverse the desert when the states they served, and consequently governance, collapsed.

Put another way, African states have the responsibility to ensure that policy, infrastructure, and adequate law enforcement are aligned throughout the continent. Africa needs to be a decentralised empire, not in political government but in trade policy.

Of the 54 African countries that have signed the AfCFTA pact, 43 of which have deposited their instruments of ratification, only 3 African countries, Ghana, South Africa, and Egypt, have met the custom requirements on infrastructure for trading. This is barely progress given how critical it is, especially in light of global supply chain shocks that have exposed Africa’s vulnerability, especially in agriculture to distant geopolitical conflict.

There is no need for another conference, summit or, put plainly, photo op to smoothen the wrinkles with AfCFTA as it exists. Governments only need to do their job—and in the absence of camera lights.

From the Cabal

Fintech startup, Afriex facilitates money transfers in any currency, from anywhere in the world. Read more about it wants to ease remittance for Africans here.

Have a great week.

Thank you for reading The Next Wave. Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and reply to this email to let us know what we can be better at.

Subscribe to our TC Daily Newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

| Abraham Augustine, Senior Writer, TechCabal. |