Mobile technology in Africa first shot to fame in the mid-2000s, quickly establishing dominance over the landline. In time, mobile technology and the mobile phone became the defacto way to do digital innovation in Africa. But this way—the mobile-only way—is strewn with perverse incentives and may have deeply negative consequences.

In the past decade, telecommunications providers erected their towers in towns, cities and villages, blazing a mobile-network trail across the continent. Digital innovators followed this trail, providing a retinue of “value-added” services to the new cellphone users. The resulting growth in cellphone owners and the versatility of the device allowed innovators to build clever products like M-PESA, the mobile money product that dominates East Africa’s payment system. You’re probably familiar with this story.

The benefits of this rapid uptake of mobile phone technology were immediate and clear—improved communication and new digital services. But the fast adoption has masked a longer-term problem.

“The point is that access is good. Access is desirable. Access is powerful. But ultimately, a foot in the door is not the same as a seat on the table.“

Mobile-first-oriented technology inherently focuses on consumption over production. The news, social media, email newsletters, game and e-sports are all centred around driving significant consumer user activity. When Africa’s technology is mostly consumption-level deep—”creating” on social media does not count—we have a problem.

For Next Wave this week, we discuss three ways this problem manifests.

The mobile software glut

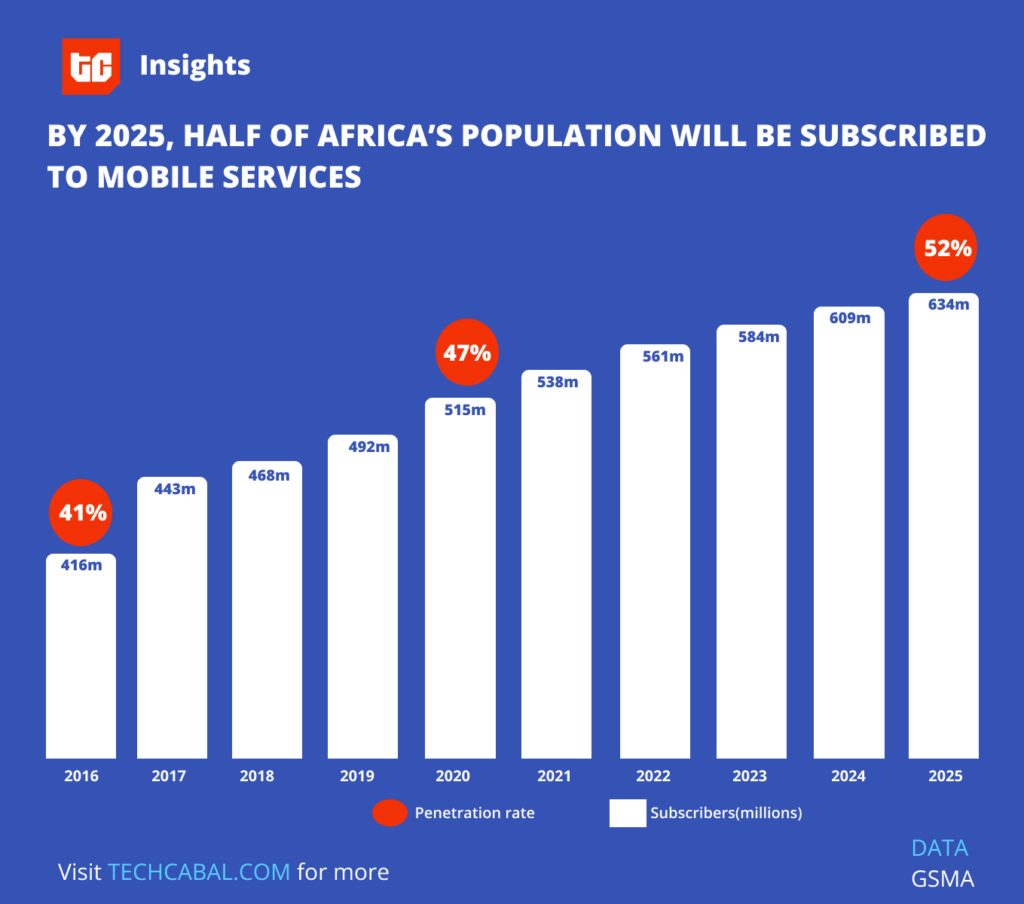

“Africa is a mobile-first continent” is the insight that shapes conventional wisdom about building technology for Africa. Founders, investors and the media hungrily track the latest mobile phone penetration data as a proxy for determining if a market is ready for a new tech product. It seems we have come to accept that if x number of people use mobile phones, they will also use our mobile phone application.

It may be true, to an extent, but there is a hard limit on who will use your new application and what mobile software can solve or produce.

One mal-incentive of a prolonged and predominant mobile-first strategy is that innovators are encouraged to prioritise “access” software solutions over deeper technology stacks. One result of this is an ever-increasing number of half-measure mobile software applications.

When people say that mobile-first products are the future they are mostly referring to the future of consumption. Not production. Unless you can conceive a future where iPhones are built on an iPhone.

But things like healthcare, for example, are not primarily consumption-based. It is real people caring for real human bodies and mental problems. You can’t software-heal a suffering body.

The digital sovereignty gap

Mobile carriers in Africa played an important role to kickstart the mobile telephony revolution. Unfortunately, African governments allowed these companies’ pioneer and occasional monopoly status to go largely unchecked until recently. That unchallenged edge allowed these companies to first maintain exorbitant prices for bare minimum service, and then make deep inroads into Africa’s digital and technology space—not merely as participants, but as controllers.

The argument is not that telcos are unregulated. It is that they are poorly regulated. Alongside working to enhance service quality, policymakers need to set the tone and own the conversation about how digital infrastructure is built, by whom and for whom.

Mobolaji Adebayo – TechCabal Insights

As it is today, African states’ involvement in the development of their digital infrastructure, outside the odd event here and there, is limited to issuing licenses and collecting the occasional fine for light regulatory infractions. This is hardly sufficient given the fact that global political interests are engaged in a lite war over Africa’s digital future.

By allowing private and usually foreign-owned (or beholden) telcos to have the upper hand in the lucrative data market, African governments have given up control of the digital economy whether they realize it or not. To get an accurate sense of how much the mobile-first inclination costs in digital sovereignty terms, consider that: “critical infrastructure – namely, submarine cables, terrestrial fibre-optic networks and data centres – needed to ensure the continent’s connectivity and the growth of a full-fledged digital economy is either partly or wholly owned by Africa’s top five telco operators: MTN, Orange, Airtel, Vodacom and Etisalat,” according to The African Report.

In return, telcos are leveraging their big budgets and large infrastructure spread to channel expansion dollars and efforts towards short-term profit in Africa’s hot but tight mobile payment space.

The status quo trap

As mobile telephony developed in the ‘90s, a mobile-first Africa was the natural outcome given the lack of landline infrastructure. At the time, we needed the access that this new form of digital communication provided and which innovators leveraged to build the M-PESA’s of this world. It was once novel, but it has now become the status quo.

But the innovation sphere needs to go beyond serving the “mobile-first” norm. We may have leapfrogged from landline phones into rapid digital expansion, but we cannot skip production into a service economy—especially if we are primarily consumers. We need to make things. And the hard truth about making things is that there are very few things with any significant economic potential which we can make on our feature phones, iPhones and Androids. Not even these devices.

Partner Message

So instead of reinforcing the lack of production by encouraging innovation to follow the mobile-first—actually mobile-only—path, we may be better off executing a strategy that appreciates and engage with the digital economy as a core part of Africa’s economic and social story.

Being mobile-first and mobile-only is a commitment to the status quo. It binds us to the external capitalist and political limitations of the makers of the phones, no matter how good a software-developer cohort the continent produces. It is implicitly saying that whereas Africa’s technology space may be growing, her digital future remains the preserve of—mostly—mobile network operators and foreign technology oracles, to shape at will and with eager approval from docile government ministries.

This depressing vision of the future does not have to be inevitable.

To summarise. The point is that access is good. Access is desirable. Access is powerful. But ultimately, a foot in the door is not the same as a seat on the table. We have our foot in the door, we must progress to sit at the table.

■

We’d love to hear from you

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

| Abraham Augustine, Senior Writer, TechCabal. |