In June this year, Ghana launched a new development bank, its fourth—to provide long-term, competitively-priced loans to SMEs that have long been underserved financially. The launch has been cautiously hailed locally and internationally as a step in the right direction, but does Ghana need another development bank, even for SMEs? The short answer is no. The longer answer is why you should read this piece.

The main argument in favour of Ghana’s latest development finance bank, Development Bank Ghana, is that a new bank will assist small businesses that are shut out of the credit market due to high-interest rates on short-term loans. Per the Bank of Ghana (BoG), the country’s apex bank, commercial banks in Ghana give loans at an average of 22.5%. The BoG’s data stops in May, 1 month before Development Bank Ghana launched. These days, following the central bank’s decision to increase its benchmark rate by 300 basis points (i.e by 3%) to 22%, business loans are even more expensive.

So, on the surface, it does make sense to create a bank which can provide cheaper credit for small businesses.

But creating a new institution no matter how narrowly focused the institution is, does not guarantee that the institution will have the power and, in this case, the financial capacity to adequately address the problem of SME financing.

Why more development banks are not the answer

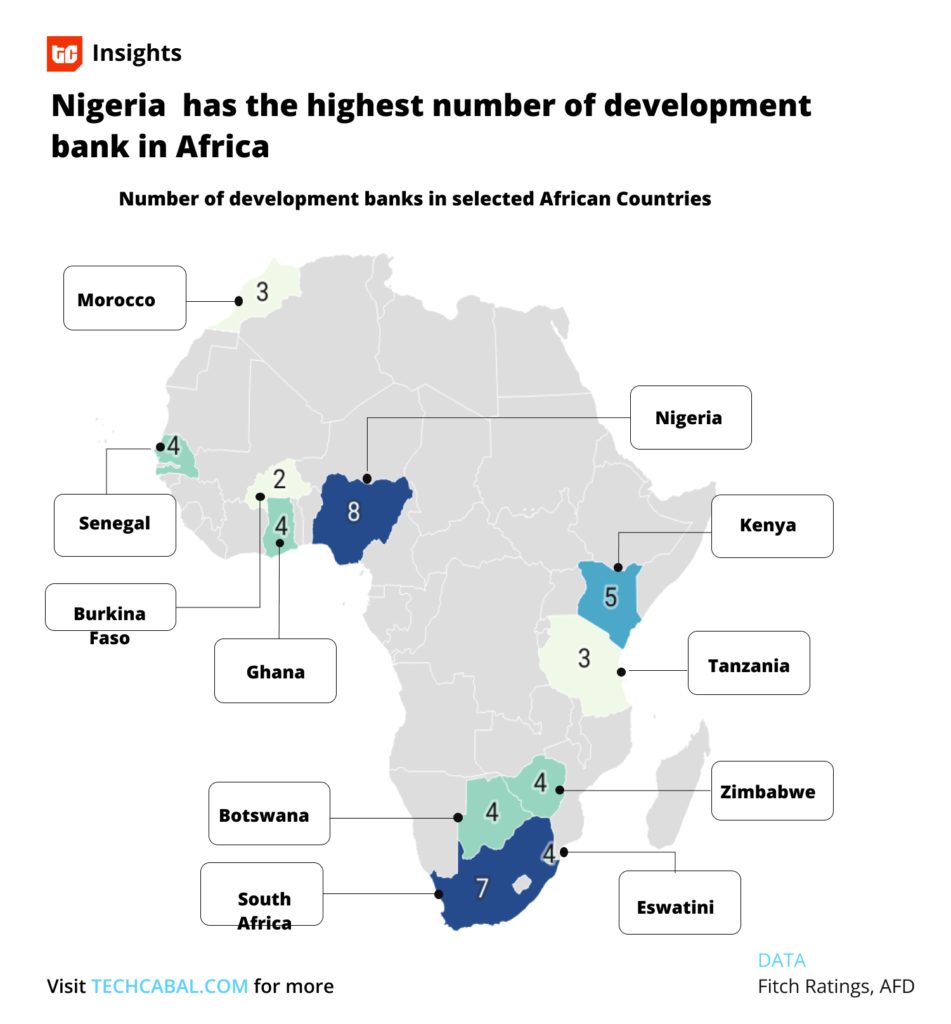

Africa has 95 development finance institutions. 86 are national development banks. Eswatini alone (population 1.1 million and GDP $3.2 billion) has 4 national development finance institutions. Together, Africa’s national and multilateral development finance institutions make up 21% of national and regional banks worldwide but collectively account for only 1% of the assets owned by development banks worldwide.

Only a few African development banks control most of this 1%. These include national banks in Egypt, South Africa, and Morocco, the regional African Development Bank (AfDB) Group and the African Export and Import Bank (Afreximbank).

Chart by Fikayo Idowu – TechCabal Insights

With development banks trying to raise capital and with varying processes, capital goals, internal governance controls and often overlapping mandates, it is hardly surprising that their assets and impact have been muted.

This is not the first time African governments have experimented with national development banks. National development banks were part of the policy apparatus in the state-led growth models of the 1960s and 1970s in Africa. By the 1990s, many of those banks had failed and a few were privatised mainly due to cronyism and corruption.

The ones that survived and most newly created national development banks remain mostly small and under-capitalised. Ghana’s DBG is the most recent example.

But African governments seem to have an undying fascination with the new. New cars annually, new stadiums, new cabinet portfolios and well, a new state-owned power utility to compete with the existing and failing state-owned power utility.

Dr. Nimrod Zalk, an Associate Professor at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town and who I owe the inspiration for this piece, argues for “the consolidation of fragmented and under-capitalised national banks into larger sub-regional development banks” instead of the creation new development banks.

Development finance is important because it helps de-risk investments in areas where private investors are less likely to put up money. By providing long-term loans or patient equity capital, development finance institutions support the case in favour of, and economic outlook of investment opportunities in Africa.

It is arguable that creating multiple development finance institutions can have the opposite effect of crowding out private investment instead of catalysing private investment.

What Africa needs instead are development banks that are big enough and independent enough to commit significantly more capital strategically versus sowing pitiful seeds and expecting a miracle bumper harvest.

Consolidating Africa’s national development banks at a regional level has the added advantage of making it difficult for national politicking to interfere with internal governance and working capacity of these banks.

Every new edition of Next Wave makes me slightly nervous that I am building a reputation for questioning accepted wisdom. I assure you, it is unintentional but I am happy to be of service. The truth is that to say that African nations do not need new national development banks is to argue for more regional integration in Africa. It is effectively saying Africa is better—at least fiscally—as a handful of regionally clustered countries, and I fully understand that.

That said, Development Bank Ghana is here. Armed with (a paltry) $700 million, it has to prove that it can do material good and catalyse the inflow of substantial private capital to Ghanaian SMEs. It has to do all this sustainably and in a worsening economic environment. It is not ideal, but it is here and I wish them well.