It’s not as old as the Egyptian hieroglyphs, but the continent’s journey to digital innovation holds lessons for today. The bad news is that we’ve mostly not cared.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of recent memory and lose the context and lessons from where we started. Africa’s digital ecosystem is often discussed as something recent and from the past five years. And any conversation that goes 10 or 12 years into the past equals ancient history

Some of this is understandable. A lot has changed, and a lot more is changing every passing hour as the continent’s digital reality becomes a separate and fully dynamic force of its own.

At the same time, nothing much has changed. A lot of the conditions that predated the digital revolution, as it is called, still exist or have become worse in some cases. In other cases, the problems have transformed into subtle and not-so-subtle bottlenecks on the road to digital prosperity. In a digital ecosystem defined by high-growth mobile app startups and Silicon-Valleynomics, the missing context of how we got here is already exacting a huge price.

If there is anything Africa’s current crop of founders, operators, and entrepreneurs need today, it is conversation, stories and lessons from how the continent’s digital economy got the ball rolling.

Why

Nothing is new under the sun, the good book says, or to quote extensively from Russell Southwood’s new book, Africa 2.0: Inside a continent’s digital revolution:

The first cohort of sub-Saharan African start-ups appeared in the 1990s: in 1995 South African Mark Shuttleworth founded Thawte Consulting, which specialised in digital certificates and internet security: four years later, in 1999, he sold the company to Verisign for US$575 million. In 1998 the US-based Africa Online, which is arguably the ‘Africa start-up zero’ outside of South Africa, relocated to Kenya. The arrival of Mark Davies’s Busy Internet in Ghana in 2001 (see Chapter 2) spurred the creation of a whole community of first-wave start-ups.15 In the same year the G8 Dot Force Initiative set up Enablis to help entrepreneurs in Kenya and South Africa. As already outlined in Chapter 6, during this period there was a great deal of interest from some donor-funded organisations (like IICD and IDRC) in using the internet to address a range of development goals in a more entrepreneurial manner, and the World Bank started funding incubators in 2008.

Africa 2.0 – Inside a continent’s digital revolution

Africa’s startup ecosystem might look young, but do not be deceived, it only looks that way and is a symptom of our lack of intentional documentation of progress. If Southwood is correct in locating the “first cohort” of African startups as early as 1995, then the “nascent African ecosystem” predates Google. Sure, “IT companies” like Thawte Consulting may not have described themselves as startups, but a half-billion-dollar private exit within four years is a feat that we’re yet to replicate even today.

What is really nascent is venture funding and this perspective resets a few things and raises some questions, like: why did we start to define the digital ecosystem as the venture capital market? And why are we building or supporting VC as the narrative of Africa’s technology ecosystem?

Why should startup founders and ecosystem players learn their history? So that things like a venture downturn will not automatically mean the cessation of existence and the dusting off of resumes. I more than suspect that getting the historical narrative of Africa’s technology development will help us discover business sustainability strategies and exit opportunities that have been lost to our obsession with venture funding.

Inside a continent’s digital revolution

Earlier this year, I became acutely aware of how little I knew about the foundation of Africa’s digital ecosystem. In conversations with myself and a few acquaintances, it was apparent that the knowledge gap was a blindspot a lot of us were suffering from. Osaretin Asemota’s (board chair at EdoInnovates) mini-history tweets whetted my appetite.

Seven years is a long time, and it’s easy to form assumptions from the past seven years of African technology. But seven years is also very brief, and as we’ve seen, Africa’s digital journey is much older than seven years. In fact, as Russell Southwood, CEO of BalancingAct, a research, and consultancy firm focused on telecoms, internet and media, shows in his book (mentioned earlier and available here and here), Africa’s digital journey can be traced back to 1986—35 years ago!

Southwood traces the development of mobile technology from 1986 to the VC-backed startups of 2020. From the brick-like Telecel handsets that became the definitive status symbol of Mobutu Sese Seko’s Zaire, revealing that at one point, Telecels, as the Motorola handsets were called, became dress accessories. Foreshadowing the ubiquity of mobile devices—at least in urban Africa. Nine chapters of stories, analysis, and illustrations show how far we have come and hint at how far away we still are.

By 1989, the network provided coverage in the country’s five largest cities. Having a ‘Telecel’ became an important status symbol locally. A newspaper article of the time gave four tips for success in the country: ‘Hire a bodyguard. Drive a Mercedes. Always wear a double-breasted silk suit. Never, but never, be seen without a Telecel mobile phone in your hand.’

Africa 2.0 – Inside a continent’s digital revolution

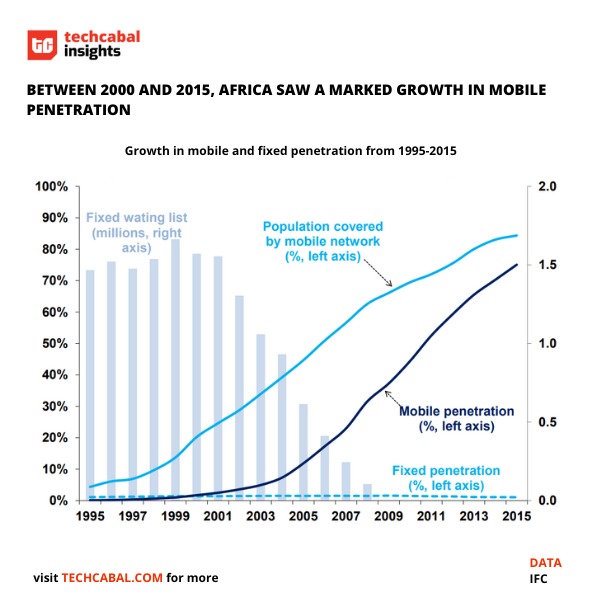

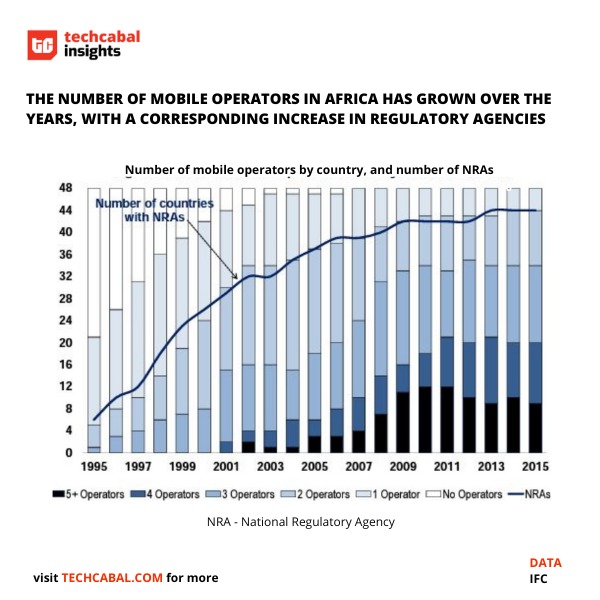

The story of Telecel, with some modifications, was the story of the first non-state movers in Africa’s telecommunications space. As early as 1989, the company demonstrated that even in Africa, a business could be built out of connecting people. In the early 2000s with mobile carrier networks, this became a reality. Africa’s mobile boom was both a proxy for and coincided with the so-called Africa rising.

“Sub-Saharan Africa’s first mobile phone operation was launched by Telecel in 1986 in what was then called Zaire (now DRC). Zaire was run by Mobutu Sese Seko as a country for which the word ‘kleptocracy’ was invented. Because Telecel was so far ahead of its time, the business was very much cast in the ‘old Africa’ mould: it needed to ‘grease the wheels’ with key politicians and became heavily dependent on their goodwill to keep operating. Its business model was one of selling scarcity expensively to elite customers. Before the launch of Telecel in Zaire, the country had only a monopoly fixed-line incumbent telephone company. There were only twenty-four thousand phone lines for a country of thirty million people. Calls often failed to go through, and when they did the quality was very bad. Most of the company’s infrastructure had not been updated since the 1960s and people often stole and sold parts of the copper network.”

Africa 2.0 – Inside a continent’s digital revolution

Like Telecel, several first movers in privately owned and operated telecommunication services have not survived intact to this day. But more importantly, Telecel’s embrace of and later struggle against kleptocratic patronage hinted at the struggles later players would face.

Underneath a continent’s digital revolution

The seventh chapter of Southwood’s book opens with a summary of the fall of Isabel dos Santos, daughter of former Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos. Under the elder dos Santos, granting of shareholdings to family and political allies was a consistent theme—a practice that is by no means unique to Angola in Africa.

The collapse of Isabel’s empire and wealth—mostly consisting of her holdings in Unitel, Angola’s largest telecom operator—highlighted how susceptible Africa’s digital revolution, especially at the infrastructure layer, is to institutionalised corruption.

Chapter 7 is fascinating reading. Not because it reveals anything not previously in the public domain, but because in little more than a dozen pages, it packs example after example of the institutional and private corruption that stain the history pages of Africa’s digital world. To put it starkly, in many cases across the continent the digital services “revolution” has been built on bribes.

It has not changed today. For example, when MTN Nigeria faced a $5.2 billion fine over its failure to register SIM cards, an MTN employee gave 500 million naira to President Buhari’s late chief of staff, Abba Kyari, Southwood recounts. The MTN employee was fired, but the findings of an investigation into the affair were never made public. MTN’s fine was reduced to $1.7 billion. Southwood also mentions fairly recent (2020) news reports of allegations of bribery leveled against Chinese telecoms infrastructure giant, Huawei in Ghana and Zambia.

If we have learned anything in 2022, it is that software is not immune. The ecosystem has been pummeled with stories of fraud, some proven, some disproven, and some still up in the air, but leaving no doubt that software companies are not inherently saintly.

If we have learned anything in 2022, it is that software is not immune. The ecosystem has been pummeled with stories of fraud, some proven, some disproven, and some still up in the air, but leaving no doubt that software companies are not inherently saintly.

Personally, the effect was to make me more of a cynic than I already was. It is good medicine, that cynicism. For entrepreneurs, investors, stakeholders and journalists covering African tech, ingesting a few doses every now and then is a must. At the very least, you know where you stand and will not come across as naive when the inevitable (for now) demands are made.

It’s been said before and by many that you cannot innovate your way around the social, political and institutional problems that keep Africa where it is today. The reason for this basic fact is simply that people make money from the inefficiencies and roadblocks. As we celebrate, each year, the increased investment being made into African tech, let us keep in mind that where big money goes, big problems follow. In the software category, we’re only at $5 billion. Are we ready for $180 billion?

This is one of the lessons of Africa’s digital revolution; that there are savory opportunities, an abundance of hardy entrepreneurs and operator talent. But also that there is no shortage of market and institutional cul-de-sacs and ethical Catch-22’s to resolve along the way.

Dear reader!

2022 has been a wild ride in the African tech ecosystem, and we have played a critical role in covering the players, the human impact and the business of tech in Africa. We have provided the content, reported the data, asked questions, and organised events to help you understand how tech is changing Africa.

Now it’s time to take stock. Please take a few minutes to share your thoughts on how we did in 2022 and what we should do better in 2023. By filling out this survey, you stand the chance to win a $50 gift card!

Thank you for your time!

Click here to tell us how we did in 2022We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

Abraham Augustine,

Senior Writer, TechCabal.