Staff of nightclubs in Lagos, Nigeria are witnessing a drop in revenue as the resultant cash crisis from the Central Bank of Nigeria’s demonetisation drive continues to drown the cash spray culture in clubs. This raises questions about the impact of the latest monetary policies on the nightlife ecosystem, a ₦500-billion ($1.85 billion) sector that is now bereft of cash.

Cash is king on Nigerian streets; even the forces behind the cashless policy drive would agree. At Lagos clubs, money changers sell freshly minted naira notes to club clientele who, in turn, use these notes to reward pole dancers and club staff for their work.

“Cash is usually a big deal around here,” an employee of Quilox, a high-end nightclub in Lagos, told TechCabal under condition of anonymity.

“Usually, the clubbers come in with wads of cash or they buy them from money changers here. Then these guys spray the money all night. Eventually, everyone gets a share, including their friends, the serving staff, and even the exotic dancers on their poles. Sadly, all that has changed since the cash crisis started,” the employee revealed.

This Quilox employee is one person from a pool of thousands who make a sustainable living from the nightlife system in Nigeria. These nightclubs depend on their staff, usually tall, pretty and slender women, to increase the appeal of the club as they shuffle between serving tables and dancing to music all night.

For all their work, these women are paid a mere ₦50,000 ($108.5)–₦100,000 ($217) monthly. But the relatively low salaries mean little to them because, according to the aforementioned Quilox employee, cash handouts from the club’s patrons multiply their monthly salaries.

It’s no longer raining cash

At Vertigo, another premium nightclub in the high-taste Victoria Island area of Lagos, the story is similar. The money changers are regrettably cashless, and fewer cash bundles are finding their way to new hands.

“There’s less cash for the ballers [revellers] to flex with these days, so spraying has reduced significantly. Even the exotic pole dancers are not getting sprayed as they used to,” an anonymous hostess at Vertigo told TechCabal.

Spanish pole dancers at Quilox, who make upwards of ₦2 million ($4,342) at every appearance, have reportedly reduced their frequency at the club due to the cash crunch.

At nightclubs like Vertigo and BayRock, dollars are becoming increasingly popular as a means of exchange—both for showy spraying and bill payments.

The cash spray economy is drying up

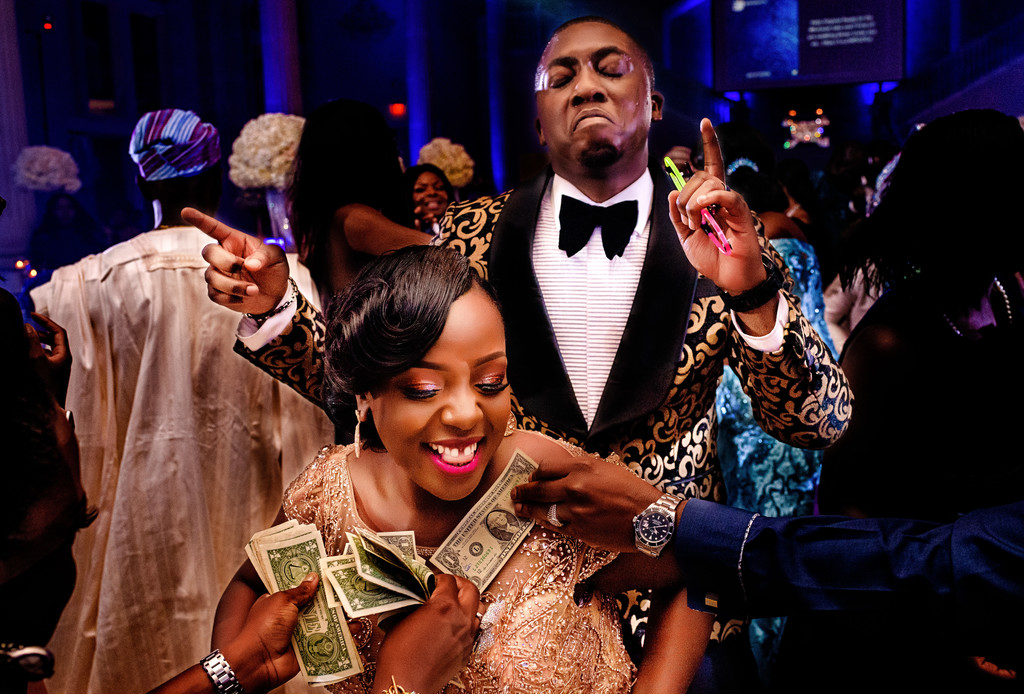

Spraying money as part of celebrations has been a Nigerian thing for decades. It was widely popularised during the oil boom years, just after the country’s independence. In Lagos nightclubs, spraying money is a surefire way to announce one’s affluence.

This presented a livelihood opportunity for a category of women—pickers—who party at clubs with the ulterior ambition to load cash from the ground into their purses. They too are now facing the pains of the cash crisis, with their average monthly revenue slashed from about ₦400,000 to an average of ₦40,000.

“Ballers now have to pay almost double for the mint notes they get, and at that kind of price, you bet they’re now more careful who they spray money on—mostly their friends, not random pickers in the club,” a staff of Ambiance, one of the top-rated nightclubs on the Lagos Mainland, said to TechCabal while maintaining anonymity.

To win at Ambiance, these ladies have to upgrade to the most classy versions of themselves and hope to be handpicked to sit at tables where they can associate with the club’s affluent patrons.

Even this win eventually brings in a third of what it used to be in the good old days, just before the Central Bank of Nigeria governor, Godwin Emefiele, launched a series of monetary policies in Nigeria.

For the nightclubs, the cash crisis means electronic methods are now the primary means of payment, and business could very well continue as usual. But the instability of some infrastructural elements of the nightlife ecosystem, including the access to cash and the presence of women who make the clubs appealing to clientele, raises questions about how far the cash problem will affect the industry.

“If I don’t see cash tips, then this job is not worth the stress. The salary is rubbish,” the aforementioned Quilox employee maintained.