President Buhari signed 16 bills into law last week in a bold move that will bring changes to several parts of the 1999 Constitution. Amongst other things, the assent of the presidency will devolve power from the Federal Government to the states, making it possible for states to generate and transmit electricity within their borders. The president’s move has been lauded by many as a long-desired win for national development, as it finally gives state governments the power to stabilise electricity within their regions. However, questions remain unanswered about how this will be implemented, and what it could mean for the tech ecosystems across the country.

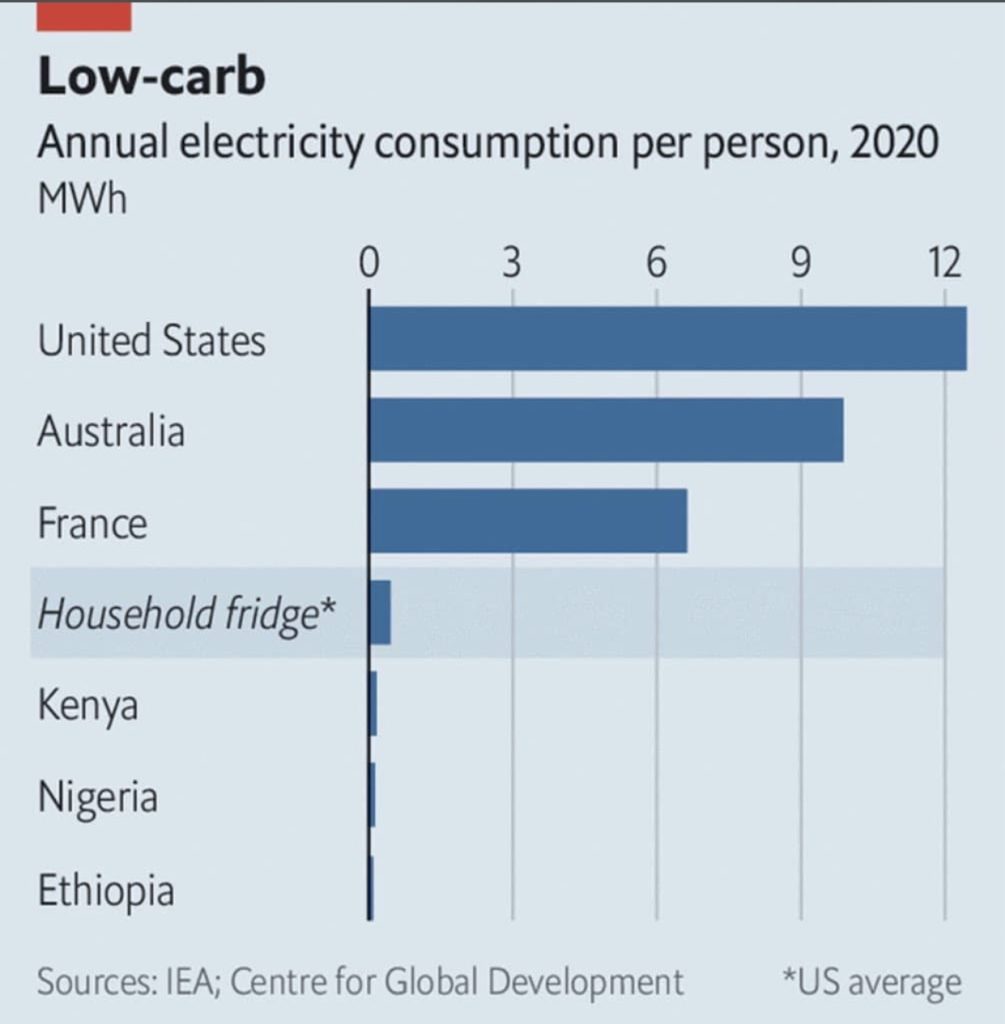

After 63 years of independence, Nigeria is still unable to supply reliable power to its citizens. The country generates only 12,522 megawatts(MW) of electricity, way below capacity for its 200 million people (45% of which are not connected to power). In comparison, Norway, a European country of approximately four million people, produces 36,000 MW.

There are many reasons for this power shortage: infrastructure deficit, lack of policy support, poverty, and sheer complacency of some government agencies. However, there are arguments that these reasons are particular to only a handful of states within the federation. Others, like Lagos, are well-resourced to consistently light up the state, but have been stifled by the centralised system of power generation and transmission. Now, the restrictions are off. How will the states respond?

Chinedu Amah, energy expert and founder of Spark Nigeria, believes that the ambition of state governments will drive the power narrative in the country over the next decade. State governments will have to get into a negotiation room with the sector’s regulatory body, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC). Together, they can review the existing policies that have kept only a handful of operators in the Nigerian energy sector and formulate new ones to guide all players in the widening ecosystem. Following that, the focus should shift toward attracting significant investments that improve the power situation across the states.

“Despite the new legislation, reliable electricity will not fall in the laps of just any state. Governments at state levels must be ambitious enough to work for it. One way they can do this is by bringing in huge private investment opportunities and formulating policies that will protect and attract investors. Institutions with the capital to build plants and energy infrastructure should be incentivised through initiatives such as tax reduction, industrialisation, and the creation of free trade zones. At the end of the day, if there are no off-takers, there’s no point in producing more power,” Amah explained to TechCabal.

Amah’s point is validated by the current reality in some Nigerian states, like Rivers, where there are up to five generating plants, but the electricity supply hardly remains reliable. The plants in Rivers state have an installed capacity of 1,800 MW, which could ensure more reliable power, were the state government distributing within the state alone. However, channelling such amounts of power into homes and offices would mount up debt as offtakers may not be able to afford the high tariffs. For context, Rivers, despite being one of the richest oil-producing states in the country, is one of three states in Nigeria with the highest unemployment rates: 47%. Also, some states in Nigeria have less than a dozen operational manufacturing industries, proving the need for robust investments if power distribution is to be increased.

Meanwhile, it is noteworthy that states have always had the legal right to distribute electricity. However, they were limited to areas not connected to the national grid. The amended concurrent list now allows states to manage the power chain in all areas of the state.

Lagos may be the first to leave the lights on

Lagos, Nigeria’s digital epicentre and technology hotspot, may be the first in the country to provide consistent, state-wide power supply. Pursuing its megacity ambitions, Lagos has since made plans to bring reliable power supply to its population of over 21 million. In 2019, the state welcomed initiatives for 24/7 power supply and has followed up with efforts of its own to replicate the feat in some residential estates across the country.

According to documents seen by TechCabal, Lagos has a proposed plan to introduce 20 solar PV power plants by 2030, each with a production capacity of 100MW. The renewable energy generated will shift the state towards greener power while providing sufficient energy for industries and residences within the state. The solar power plants are to begin functioning by January 1, 2025.

Morakinyo Beckley, a former Special Assistant to the President on off-grid power, agrees that Lagos is probably the most prepared state to provide reliable power supply to its citizens. “Lagos, in partnership with the USAID, is working on an ‘integrated resource plan’ that will boost power generation in the state. Even before that, Lagos and some other states including Kaduna and Rivers, have ventured into some independent power projects for their states. These states have already built the rails for reliable power; they are best equipped to keep the lights on,” he said in an interview with TechCabal.

How will state-generated electricity improve tech ecosystems?

“More power, more progress” sums it up. Technology, across its various verticals, is intrinsically tied to the availability of power. Whether it’s for large data centres or small startup offices, having reliable power supply will always be a booster for operations and can multiply output exponentially. In 2020, the economic cost of power outages in Nigeria was estimated at $2 billion, equivalent to about 2% of the national GDP. Such power outages tremendously affect the ease of doing business in the country, as businesses have to create huge budgets for the constantly increasing fuel prices. This situation altogether reduces the already slim odds of success for tech-powered upstarts. If the power situation is turned around by state-powered electricity projects, then chances are high that the tech ecosystem in such regions would naturally mature quickly.

Additionally, improved electricity distribution will pull investors and multinationals to the states that are able to pull it off. This could ripple into a wider spread of industrialisation and technology hubs, as against their current concentration in only a few states. Several reports highlight electricity as a major factor influencing the mass migration to urban cities. A former governor of Lagos, Akinwumi Ambode, put Lagos’ figure at 123,000 daily migrants—a good explanation for the state’s overpopulation.

When more states are able to pull off reliable electricity within their region, they will welcome an exodus of people from highly urbanised climes. Many of these people would be remote tech workers who’d rather not face the glorified rigours of the Lagos lifestyle. Companies and manufacturers will move too, as long as the incentives are there. Overall, this move by President Buhari to devolve power to the state governments could be the solution to Nigeria’s power crises. But the reality is, as Chinedu Amah says, execution will largely depend on the ambition of the state governments.

“With states in control, they can license new operators across the power chain, ultimately driving competition and reducing prices for offtakers. This is cost savings for businesses. We can also expect a significant drop in noise and air pollution caused by prolonged generator usage. Telcos, for example, will transfer the cost savings to the customers, causing a drop in the cost of mobile services like airtime and data. A win for everybody, really,” Beckley concluded.