The gender gap in tech careers continues due to inhibitive gender norms and the gender gap in tech education.

“My superior at work is a woman. The two best backend engineers on our team are female. So when people talk about gender inequality in the tech ecosystem, I do not see it,” Philip Awotepu, a product manager, said to me at a party. The party was to celebrate the graduation of 18 youngsters who had spent 12 months learning at Semicolon, an ed-tech startup that offers cohort-based training in tech skills like engineering and product management. This party was for its 11th cohort, with 30 graduates, of whom only eight were women. In the previous cohort, 36 graduated; again, only eight were women.

The product manager’s assertions in the face of real-life contradiction mirror a stubborn belief that gender inequality in tech careers is a natural outcome based on divergent interests between the sexes or it is being blown out of proportion. This belief makes people frown at and sometimes protest initiatives or policies that exclusively support or prioritise women. For instance, in 2021, Kuda Bank was accused of discriminating against men when it advertised internship positions exclusively for women. After receiving many negative reactions to the tweet about the internships, the fintech explained that it was trying to close the gender gap in its team.

Similarly, Semicolon—which trains both women and men—has a separate mentorship programme exclusively for its female trainees: SWiT (Semicolon Women in Tech). Interestingly, Awotepu was volunteering as a mentor on SWiT. He shared that he initially had no idea it was exclusively for female students. However, he mentored one of the few ladies graduating that day who had learned product management and landed a paid internship at the popular fintech company Moniepoint. “During one of our mentorship sessions, she shared concerns about being the only woman on her team. I told her that no one cared about her gender and all she had to do was do great work, and she would be okay,” he recounted.

She probably agreed with him on the call, but her experience before entering Semicolon begs to differ. “When I told my parents that I wanted to move to Lagos to train at Semicolon, my father asked me whether I didn’t want to get married,” the mentee said to me in a later discussion.

If she hadn’t been committed and ready to leave all that was dear to her—her family and friends—in Kano state and move into a shared apartment in Lagos with the few other ladies who were attending Semicolon as well, she might not have taken up product management, a skill that pays within ₦100,000–₦300,000 in Nigeria. “I knew I wanted to change my life for the better,” she said.

Her experience, echoed by many other women across Africa, answers a weighty question: “What barriers do women face in acquiring tech skills that men don’t?” The first and perhaps most important answer is that many religious and cultural beliefs suggest that a woman’s most useful role is homemaking and nurturing children. Nafisa Idris, a data scientist who also mentors women who are interested in a tech career, told TechCabal, “[After my father died,] our uncle tried to get me married at age 11, but my mother refused because she had promised my dad that she would make sure I was educated as much as possible.”

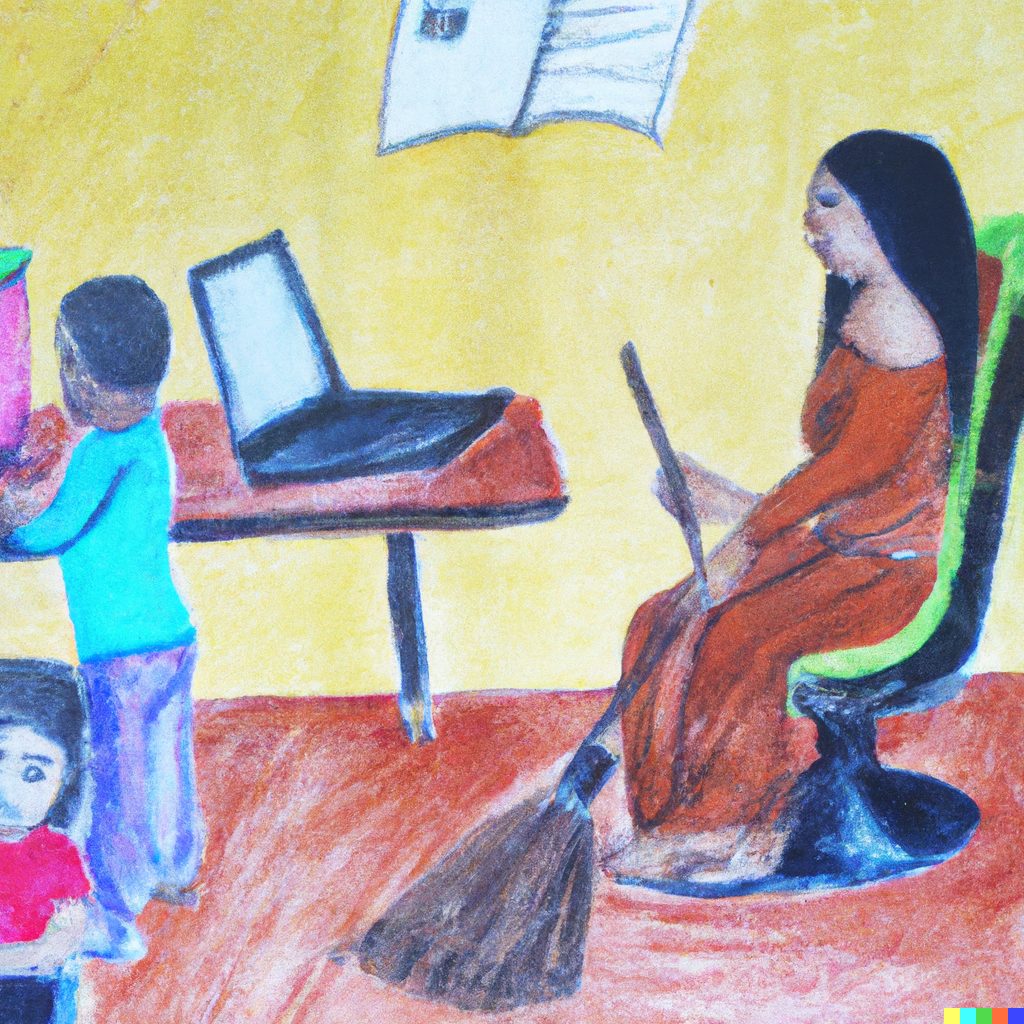

Even when women are just as educated as men, their productivity is hampered due to the gender roles expected of them, especially by their immediate family. A 2023 research paper tried to probe why educated African women in science and technology published fewer papers than their male counterparts, and it discovered that it was because a greater proportion (≥50%) of care work, family commitments, and housework in the home are overwhelmingly performed by women. Women would make more contributions if they were not so constrained by these responsibilities.

Nearly 74% of respondents to a survey created by TechCabal commented that the cleaning, cooking, and caretaking chores leave them exhausted and with little to no time to learn tech skills, even when their families know they are enrolled in such programmes. “I’ve had to take classes with my laptop in the kitchen [while cooking], and most times because [I am worried about gas explosions, I have to skip classes,” said a respondent who was taking online tech skill training at a popular ed-tech.

Rachael Onoja, head of operations at AltSchool—an ed-tech like Semicolon—told TechCabal that there have been several instances of female students missing classes because they were helping their siblings get to school or handling some other family matter. “Several female students have dropped out to care for a sick family member.” Men have dropped out of school, too, but it has mostly been due to financial shortcomings, not caretaking responsibilities. Rachael believes that these gender norms or cultural expectations of women are contributing to the gender gap in the tech ecosystem.

[ad]Addressing the impact of gender norms on women’s tech skill development at the 2022 SheCode Africa conference, Semicolon’s co-founder, Ashley Immanuel, said that, out of approximately 10,000 applicants to Semicolon, many women excelled and received admission offers. However, many had to reject these opportunities due to parents’ or guardians’ beliefs that it was not a worthwhile use of resources or the woman’s time. “Those who come despite not receiving that permission may do so under the condition that their families do not provide financial support,” she explained.

Due to this pattern of women lacking access to funding, notable figures, tech professionals, and some organisations set up scholarships to exclusively fund the registration fee or full tuition fee for women interested in participating in tech training. AltSchool, which currently has a school of engineering and products, told TechCabal that such female-focused scholarships have sponsored many of its female students. “We often hear comments asking about male-exclusive scholarships in addition to the gender-agnostic scholarships, but I think that more effort needs to be made to include women if we are ever going to eventually close the gender gap.”

Semicolon’s cohort-based training takes a year and costs about ₦4.3 million. The fee covers training, a laptop, daily lunch, healthcare, learning materials, and internet access. Semicolon partners with Learnspace to make it affordable, which provides a “learn now and pay later” loan option. Participants start repaying the loan at a 20% interest rate per year, three months after they have completed the one-year training and gotten a job. According to Semicolon, 98% find employment or start their startups. Last year, when Immanuel spoke at the conference, the cumulative participation of women in Semicolon’s training was 21%. This year, it increased to 30%.

[ad]Eden, an alumna of Semicolon, sat beside me at the graduation party and overheard my discussion with the product manager. She responded with a wry chuckle at his comments. “When you’re not the one being othered, it’s hard for you to see [the patterns of discrimination],” she said. She, too, faced resistance when she informed her parents of her plans to leave Port Harcourt to learn at Semicolon.

During the programme, she had to endure her male colleagues, who took many opportunities to project cultural stereotypes on her and use them to underestimate her work. “I worked my butt off [during the training] but my male classmates often commented, ‘Why are you working so hard? You will still marry a rich man,’” she said.

The experience has left Eden worried that her gender will constantly undermine her work. At Semicolon, she trained to become a back-end engineer. But for the first six months, she and the others had to take general training that entails product management, backend engineering, and others before specialising in the one they preferred. Eden chose to specialise in back-end engineering and was assigned a male tutor. Some of her classmates implied that the instructor “spoon-fed” her during the training. This reflects a common perception that the bar for women’s excellence is often set lower than that for men in a bid to close the gender gap. People commented in this vein when Kuda Bank called for female interns years ago, and women like Eden expect it to continue throughout their careers.

Aside from the cultural norms that exclusively deter women from learning tech skills and subsequently getting tech careers, gender-agnostic challenges and barriers to tech education in Africa significantly affect women more than men. For example, both African men and women have inadequate access to mobile devices and the internet services they need to learn these skills. However, women are 30% less likely than men to own a smartphone, and there is a 37% gender gap in internet access across the continent. This skew against women in Africa and beyond is why it may take 131 years to achieve gender parity with men globally.

Attaining gender parity within tech education and, consequently, the tech job market demands recognising the existing gender gap and uniting in a shared resolve to confront the gender norms and biases impeding equitable opportunities. Organisations like Semicolon, AltSchool, and non-profit organisations such as She Code Africa, EmpowerHer, Non-Tech in Tech, HerTechTrail, and Tech Girl Magic actively forge a path toward a fairer horizon. Through scholarships, mentorships, and education initiatives focused on women, these organisations are enabling women to get essential tech skills and careers and fostering a gender-inclusive ecosystem.

Have you got your tickets to TechCabal’s Moonshot Conference? Click here to do so now!