When ride-hailing apps like Uber and Bolt launched in Kenya in 2015, they promised riders a new experience and better earnings for drivers. Nine years later, the companies have delivered cheap rides for passengers, but driver partners have seen their incomes decline.

On July 16, taxi operators went on strike for the fourth time since 2020 to protest low pay and unfair working conditions. The drivers say the fares do not reflect the country’s economic realities.

“A 25km trip is about KES1,000 ($7.52). When you deduct the 18% commission paid to the company and other charges, you’re left with very little even to service the car,” said Steve Mutisya, a 35-year-old driver.

“My car consumes one litre per 20km. If you do the math, you will see how little money I make at the end of the month, yet I have a young family.”

For a KES1,000 ($7.52) 25km trip, Mutisya would remain with about KES 569 ($4.33) after deducting KES222 ($1.69) for 1.25 litres, KES180 ($1.37) as 18% service fee paid to the companies and KES28.8 ($0.22), a 16% VAT on the service fee.

Uber and Bolt reviewed trip prices in 2022 after the Ministry of Transport capped the commission paid to the companies at 18%. That won over the drivers for some time. However, the cost of fuel and vehicle parts has increased, pushing operators to the edge.

Ride-hailing apps worry that customers are price-sensitive and that increasing fares would reduce patronage. The downside is that someone in the value chain has to take it in the neck for such a precarious business model.

Uber and Bolt did not immediately respond to email requests for comments.

Since the 2022 price review, petrol prices have increased by up to KES50 ($0.37) a litre. Vehicle maintenance has spiralled up following an import duty increase on spare parts from 25% to 35% in addition to a 20% excise tax.

“In 2022, brake pads would cost me KES1,200 ($9) and a good service between KES6,000 ($45) to KES10,000 ($75). Today, brake pads alone go for KES6,000,” Mutisya said.

The high maintenance cost has forced insurance companies to stop covering some popular car models among taxi operators including Suzuki Alto, Honda Fit and Mazda Demio.

Taxi drivers who took loans to buy cars have been left with unaffordable debt they cannot service. Kenya’s transport industry accounts for KES45.6 billion ($3.3 billion) of the banking sector’s KES651.8 billion ($4.9 billion) non-performing loans, according to the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK).

“I took a KES120,000 ($902) loan to top up my savings for this car. I had to ask for help from family to clear the debt because the money I was getting could not,” said John Munyao, a Bolt driver in Nairobi. “I know of colleagues who took loans to grow their fleet and are now struggling to repay.”

The Ridehail Trasport Association, one of the sector representatives, wants the companies to include drivers in setting minimum and base fares.

“The person who sets the prices doesn’t bear the cost of running the business,” Zakaria Mwangi, secretary general of the association, told TechCabal on July 15. “Ultimately, the taxi apps determine the cost of each trip, not the driver.”

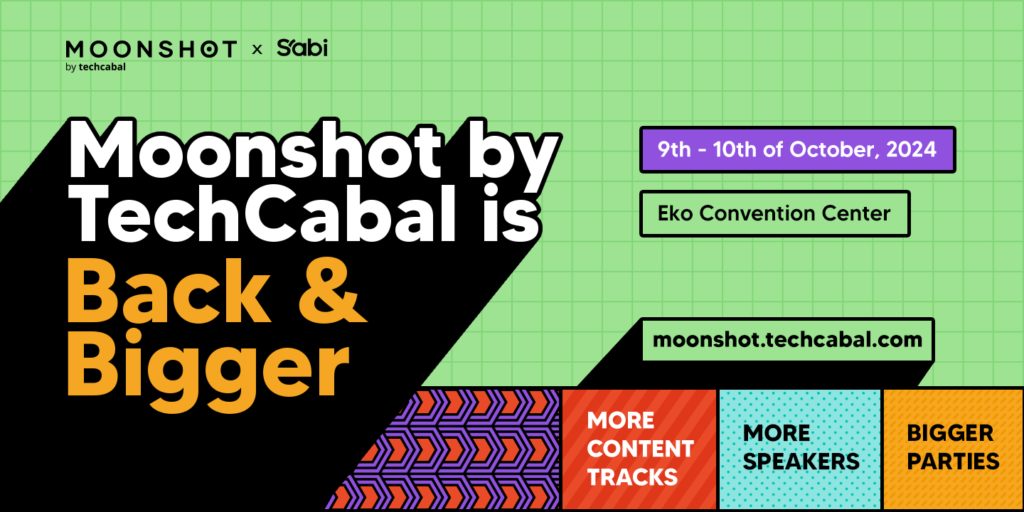

Have you got your early-bird tickets to the Moonshot Conference? Click this link to grab ’em and check out our fast-growing list of speakers coming to the conference!