In 1939, Columbia Pictures released Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a political satire about an idealistic new senator battling government corruption. Though American politicians criticised the film’s harsh portrayal, it became a classic. By 1989, it was selected as one of the first 25 films for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry.

In 2023, President Bola Tinubu appointed Bosun Tijani as his Minister for Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy. His appointment has been widely interpreted as an olive branch to the tech community and young Nigerians, a demographic Tinubu struggled to win over during his presidential campaign. Tijani has previously been outspoken in his criticism of Tinubu and the ruling All Progressives Congress, which made his confirmation process uncertain. However, after a carefully worded apology, he secured his ministerial appointment.

Tijani is the fourth minister to hold a similar portfolio since its creation in 2011. Goodluck Jonathan named Omobola Johnson as Minister of Communication Technology. While Muhammadu Buhari stuck with the conventional ministerial Communication portfolio for Adebayo Shittu, he reverted to Communications and Digital Economy for Isa Pantami.

Tijani might claim to be the first ecosystem professional to assume this post. Johnson was the country head of Accenture when she was made minister, Shittu was a career politician, and Pantami was an academic, cleric and agency executive before assuming the role. Tijani is well known as the co-founder of CcHUB, an accelerator based in Yaba, the home of Nigeria’s tech ecosystem.

But Mr Tijani did not come to Abuja to simply implement policies–a common challenge that has affected many technocratic minds invited to public service. In his words, he seeks to build and change the idea that people cannot be in government and deliver effectively. Aware of his responsibilities to multiple constituencies and his role as one of the few younger ministers, he’s striving to balance technical expertise with political acumen. Yet, whether or not he has balanced these different roles and expectations is an entirely different question.

Welcome to Abuja

Government buildings often mirror public perception: dull, static, and uniform. Newer structures look a bit modern but, over time, will inevitably follow the same pattern.

The fact that Abuja is a government city, the move designed to cater to Nigeria’s expanding government, means that this is the prevailing view. However, with the influx of civil society, international organisations, and lobbying groups, there’s a burgeoning vibrancy beyond mere bureaucracy. But the expectation can still be met when one sees and enters, the structures that determine policy and direction for an estimated 200 million people.

Yet, the office space where we meet Mr Tijani for an interview is different from a conventional civil service conference room or hall. The abrupt transition from the sterile corridor to a vibrant, open-plan office is striking. There is a large conference table in the middle, some sofas and chairs in the corner, and office cubicles in a fairly open space. Young staffers come to the table at different points to review different reports, charts and videos.

Based on the setting alone, nothing has changed about him being in Abuja, one year after. This is not your average ministry, but Tijani is not your average minister. His office mirrors the spirit of the Yaba he’s coming from, far removed from Lagos’s corporate stiffness or Abuja’s bureaucracy.

Before our meeting, we were advised to temper our expectations. Tijani had just returned from Beijing and was operating on little rest.

Throughout our conversation, he’s also aware of how, to some, he has failed to live up to expectations. He approaches government the way a start-up founder does, mindful that a rejection or a failure is simply a chance to learn, re-strategise and pivot. The lingering question is if this is possible in Nigeria’s government, where technocrats have notably been frustrated. `

Before Abuja, there was Yaba

Tijani co-founded Co-Creation Hub, a cornerstone of the Yaba tech ecosystem. He recalls advocating for fibre installation and making the case to then-Governor Fashola and MainOne about Yaba’s potential. He speaks about organisations being formed within CcHub – including Andela and BudgIt – without receiving any financial incentive when they eventually took off. CcHub provided office space and an environment for this to grow. As a forerunner in the tech ecosystem, this status would be enough for serious consideration for any government role focused on this sector.

When Tinubu named his cabinet, many viewed it as a reward to political allies who had supported his contentious election—a lineup filled with former governors and campaign staffers. However, a handful of people with technical expertise, including Tijani, who had his experience co-founding a well-known tech accelerator, were seen as opportunities by citizens to hope for a difference. Presidents typically don’t assign portfolios before Senate confirmations, but it was widely anticipated that Tijani would oversee the digital economy, given his background. His inclusion signalled a possible alignment of government policy with the perspectives of the tech community.

However, Tijani’s confirmation was not guaranteed. After all, a nominee had been swapped, and others had been dropped for security reasons. One of them was Nasir El-Rufai, a former governor and minister, who had played a major role in the campaign and spent the year outside the government. In Tijani’s case, it was not security; social media was the risk. Tweets that he had made in the past, critical of former President Muhammadu Buhari and Tinubu, were recycled online after his nomination became public. During his ministerial screening, senators referred to one stating, “Nigeria is a bloody expensive tag”. Tijani ate humble pie, apologising and spinning his tweets as being “out of anger and patriotism.” It was enough to get him a seat at the table and the chance to set about changing a sector he was only too well familiar with.

“Abuja is a reflection of our society.”

He has had to grapple with different battles and impressions since. Well-known tech ecosystem players have criticised him on social media, his tweets supporting controversial politicians have been panned, and the pace and focus of his ministry have been flayed. When Tijani arrives for the interview–apologising for the hours-long delay–he wears the air of a man with a suit of armour from a year of battles—often from his constituency, a topic we end on.

A different view of government

Tijani exudes confidence in his transition to Abuja, viewing governance as less daunting than is commonly perceived. This assurance stems from his distinct approach: he claims to be the only minister using a white paper to outline preliminary policy ideas. While not entirely accurate—the education ministry already did it—it reflects his intent to introduce new methodologies. He’s also proud of releasing a target list within two months of taking office and believes they’re on track to meet their 2024 goals.

He perceives government standards as low and aims to elevate them within his ministry. Believing that “Abuja is a reflection of our society,” he suggests government structures need reassessment to ensure they’re fit for purpose.

Contrary to expectations that his private-sector background breeds contempt for bureaucracy, Tijani acknowledges the challenges of navigating a different culture. “Government is not structured to build, but to administer—and there is a lot to build in Nigeria,” he asserts.

He contends that real power isn’t centralised in Abuja, noting, “Every ministry is still influenced by the biggest players,” many of whom are based in Lagos, the commercial hub. This suggests industry leaders—fibre providers, tech giants, venture capitalists—may wield more influence than legislators, highlighting his unique perspective on power dynamics.

That might be true in his sector, but it shows much self-belief to make such a sweeping and authoritative statement.

He also believes federal and state relations are “not as complex,” especially as the current administration aims to devolve more powers. His confidence, typically rooted in political savvy, underscores his self-assuredness in his role. Yet, he recognises that more than technical expertise is needed; adept navigation of Nigeria’s intricate political landscape is essential.

“Every ministry is still influenced by the biggest players.”

Tijani admits limitations. He grapples with coordinating with numerous ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs), acknowledging that his ambitious tech initiatives could disrupt existing budgets and cause friction. He’s candid about challenges like nationwide right-of-way costs: states desire investment but often lack incentives for industry players. His ultimate goal of transforming government is digitising processes—connecting disparate databases into a unified, manageable system.

Government officials often react rather than set agendas. Despite this, they’re pressured to show immediate impact, judged by metrics like their first 100 days. Under scrutiny from social media and pundits, they must balance adapting to bureaucracy with achieving objectives.

Tijani exemplifies this challenge by focusing on his signature initiative: the 3 Million Technical Talents (3MTT) project. More than just a passion, it’s the realisation of his critiques of predecessors he felt did little for tech advancement. By championing 3MTT, he aims to turn advocacy into tangible progress.

Ambitious or pragmatic?

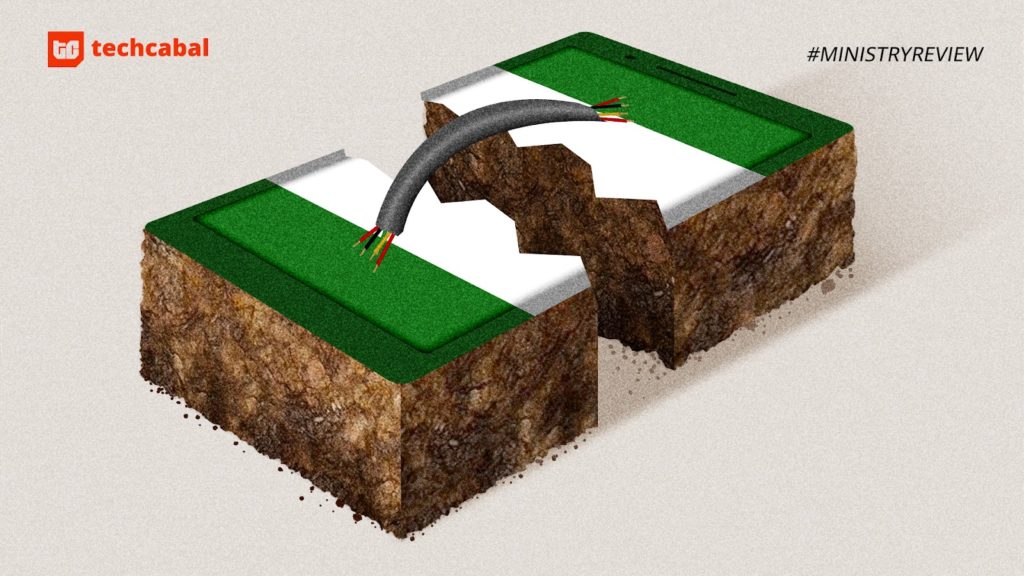

When asked what he believes will define his legacy—beyond the 3 Million Technical Talents (3MTT) project—Tijani highlights two additional areas that Nigerians frequently lament on social media: data sharing among federal agencies and fibre connectivity.

To illustrate the impact of the 3MTT project, Tijani shares the story of a woman in Kano, clad in a niqab, whose enthusiasm during a program demonstration defied conventional stereotypes of tech professionals in Nigeria. This example underscores his belief that broadening access to technological education can empower anyone, positioning Nigeria as a net exporter of talent and an importer of jobs.

For Tijani, the project is an opportunity for the government to reach a wider demographic and prepare the nation for the future. However, he acknowledges the challenge of employing newly trained talent, emphasising that with job opportunities, their passion may stay strong. He sees this as an area where the tech ecosystem and private sector must collaborate to create avenues for employment.

This acknowledgement reflects his understanding that government alone cannot drive innovation and that partnership with industry stakeholders is crucial. While there’s an extensive TechCabal deep dive on the 3MTT project as part of this series, it’s clear that measuring its legacy will require a long-term perspective.

He has also faced challenges with his aim to improve connectivity through fibre. Seven development finance institutions (DFIs) have pledged $2 billion to support this initiative—a significant investment. He is cautiously optimistic, highlighting how enhanced connectivity can boost GDP and aid security efforts by enabling intelligence agencies to better monitor countrywide activities.

However, this endeavour underscores the complexities of Nigeria’s federal structure. Tijani has engaged with various states to negotiate right-of-way discounts and facilitate accommodations for telecom companies and broadband providers, achieving mixed results. Navigating these negotiations requires political finesse, and while he’s sought assistance from politicians, this has sometimes led to controversy rather than collaboration.

Nigeria has too many datasets—from voter registrations and banking details to driver’s licences and mobile SIM registrations. Many Nigerians have called for a unified data exchange system to eliminate redundancy and enhance efficiency. While efforts are underway to address this, significant challenges remain, particularly concerning data security and inter-agency collaboration.

Implementing such a system requires new legislation and presidential approval. Tijani notes that a recent incident, where his own National Identification Number (NIN) was reportedly purchased for 100 naira, led the president to withhold approval on a related proposal. This underscores the critical need for robust data protection measures before advancing data integration initiatives.

The conversation eventually shifts to Artificial Intelligence (AI), a topic Tijani has a keen interest in. At 47, his relative youth compared to Nigeria’s older governing class positions him to champion innovative technologies. He identifies key sectors where AI integration could be transformative: education, agriculture, and entertainment.

AI can personalise learning experiences and ensure students engage deeply with the material rather than relying on tools like ChatGPT for easy answers. AI technologies can help farmers determine optimal planting and harvesting times in agriculture, improving yields. The entertainment industry can leverage AI to predict audience preferences and tailor content accordingly. While acknowledging that some progress has been made in these areas, Tijani emphasises that much more can be done to harness AI’s potential fully.

When talk turns to elections, he acknowledges that it could be ‘nasty’, with parties potentially using it to spread misinformation or manipulate public opinion. He commends organisations like Luminate for supporting the AI Collective—a consortium of stakeholders dedicated to advancing AI adoption responsibly in Nigeria.

This highlights a recurring theme in our conversation: the government’s limited capacity to drive technological change independently. Tijani acknowledges that private-sector collaboration is essential to accelerate progress. He believes his unique position as a tech-savvy minister bridges the gap between government and industry. However, questions still need to be answered about whether his efforts yield results quickly enough to make a significant impact.

The longevity question in Abuja

At some point in the conversation, Tijani highlights that the wide remit of his ministry means there are more constituents that his work will appeal to than the tech ecosystem people readily identify him with. He references trying to support the rebuilding of the postal service, supporting start-ups through a start-up house in San Francisco, and building on improved government synergy. These topics are not off the burner per se but, over one year, they will take a longer time to see efforts come to fruition.

The key question remains whether Tijani will earn the time needed to see his initiatives through. His continued tenure hinges on his ability to navigate multiple pressures: representing the interests of the tech community, delivering tangible results, and providing political utility as President Tinubu eyes re-election. These elements are closely linked, particularly as his appointment was seen as a conciliatory gesture towards a sector skeptical of Tinubu’s leadership. In Abuja, Tijani has had to strike a delicate balance between pragmatism and political manoeuvring—efforts that have produced mixed outcomes.

Tijani’s political actions have drawn criticism, particularly his tweets praising Budget and Economic Planning Minister Atiku Bagudu, a figure with a controversial past linked to former dictator Sani Abacha’s looted funds. Similarly, his support for Hope Uzodinma, the Imo Governor whose contested rise to power has remained divisive, has fueled perceptions that Tijani has become too partisan. These moves have alienated some within the tech community who once saw him as a vocal critic of the entrenched political elite.

Tijani remains unapologetic about his praise for Bagudu and Uzodinma, arguing that both have contributed positively to Nigeria’s development. He highlights their support for his initiatives, particularly Uzodinma’s efforts to bring Imo State to the forefront of ministry projects. Additionally, Tijani acknowledges President Tinubu’s support, emphasising that he was appointed without prior connections or patronage—a testament, in his view, to the sincerity of the president’s agenda. This belief underpins his continued loyalty, even after previously voicing criticism.

While Tijani has grown closer to the political elite, his relationship with the tech community has become strained. He admits feeling let down by those he once believed would understand the broader vision he presents. He laments the lack of critical engagement, with many choosing casual discussions over meaningful discourse. In his view, many within the tech sector are missing opportunities to collaborate with the government to advance the industry.

This disconnect has led to vocal critics, including notable figures like Mark Essien and Gbenga Sesan. Meanwhile, others, like Iyin Aboyeji—whom Tijani considers a close ally—have been criticised for being overly supportive. These evolving dynamics reflect the complexity of his position, caught between the expectations of two very different constituencies.

When I told some friends that I was writing this for TechCabal, I was asked if I was being hired to help the minister brush up on his optics ahead of a potential cabinet reshuffle. But Tijani doesn’t feel nervous about it. He feels supported by the president, the government and, above all, is confident that he is doing his job. And yet there are instances, such as a recent launch for a 100 million (~ $61k) AI fund, where even those who have heard him evangelise can see the cracks in the prophecy. This could be explained away as a quick win, but then a minister who can attract larger investments should not be so enamoured as to attend and sign off on it. This is one of the mystifying challenges of looking at Tijani’s work – the promise of so much more being hamstrung by the reality of Nigeria today and a government that has failed to deliver on the appeal behind its election victory. For Tijani to succeed, Nigeria itself must succeed—an uphill battle under a president whose popularity is waning.

Tijani’s tenure so far is marked by a blend of confidence and frustration. He knows his domain well and doesn’t need civil service managers to guide his work, but like many government officials, he feels his efforts are often underappreciated. His communication team has been effective in sharing his progress through weekly updates, though he has scaled back these efforts, acknowledging the impossibility of pleasing everyone.

To those who watched Tijani’s ministerial confirmation, the man now navigating the complexities of Abuja might seem far removed from his former self. Yet, both sides coexist. He isn’t bound by ideological dogma but rather driven by a pragmatic willingness to work with anyone to advance Nigeria’s tech ecosystem. However, this evolution comes at a price—he can no longer expect the unconditional support of a constituency that now sits across the negotiation table. His challenge is monumental: reforming a system built to administer rather than innovate. Whether Tijani will transform the system or become a part of it remains an open question.

Some may feel the question is already settled, but as long as he remains minister, the answer is still in play. If retained, it could come at the cost of another minister from an overrepresented state, and he may also find himself positioned as a campaign surrogate for 2027. How he communicates and to whom will depend on his evolving role and his ability to expand his reach. No matter his focus, success in Abuja ultimately depends on political manoeuvring—a harsh truth in Nigerian politics. Just ask President Jonathan.

“For Tijani to succeed, Nigeria itself must succeed—an uphill battle under a president whose popularity is waning.”

Tijani’s three most recent predecessors served full four-year terms. By that metric, he could have three more years—time enough for a thorough assessment of his initiatives and their impact. But political dynamics are rarely predictable, and tenure often defies tradition.

In “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” the protagonist triumphs when the political machinery remembers its idealism. In Tijani’s case, the parallels may end with the journey itself. Eventually, there will be a departure from Abuja, but whether it will be marked by systemic change or just another chapter in Nigerian politics remains to be seen. This story, unlike the film, offers no guarantees of a triumphant ending.