First published 03 November, 2024

How big is the pie in Africa?

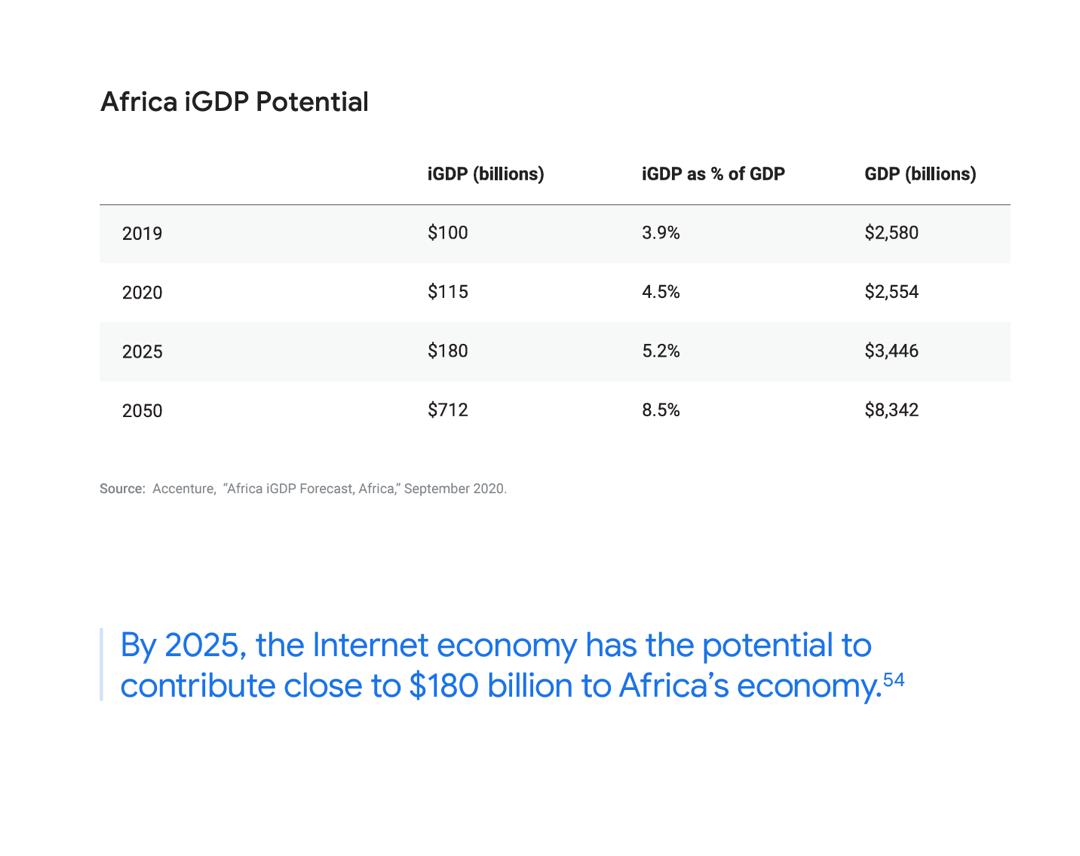

In 2020, the International Finance Corporation and Google produced a report projecting that the digital economy would grow Africa’s GDP by $180 billion or 5.2%. Since then, around $15 billion has been invested into African technology to help bring the $180 billion of economic gains to reality. Those investments exclude investments in things like connectivity infrastructure, etc.

If the report’s projections hold up, we should be near the $180 billion mark by now. Unsurprisingly, hundreds of startups have been created to chase this $180 billion internet economy, backed by more than $20 billion in venture capital investments and other forms of financing from the 2010s.

The slice of this multi-billion dollar market a startup can carve out and hold on to is part of what we describe as “scale.” The way startups choose to cut their slice gives insight into how they see scale. The two dominant approaches to scale are tech geocentrism and tech-heliocentrism.

The Geocentric approach refers to a situation where the company tries to grow market share by cultivating loosely coupled products that revolve around a winning primary offering. McDonalds is an example of a geocentric business; its menu is complementary to burgers and fries. Superapps like WeChat are the tech equivalent. Generally speaking, vertically integrated businesses are good examples of geocentric businesses.

The Heliocentric approach is a perspective in which the business seeks to grow market share by throwing together multiple products at a big (and shiny) problem area. The goal is that the products will create a strong enough force to sustain the business as a going concern. Financial services super apps or enterprise product suites like Adobe are examples of heliocentric products.

Next Wave continues after this ad.

As the race for Africa’s digital economy becomes hotter and the surrounding macro-environment becomes more challenging, African companies are treating expansion and the search for “scale” as an exercise in building geocentric or heliocentric products.

So you see more fundraise press releases hinting at growing the product library and geographic coverage. By choosing geocentricity, they add related product lines directly on top of their core offering. With heliocentricity, they develop almost detached product lines. Two recent examples come to mind: Rafiki, the payments API product announced after NALA’s fundraise, and Moniepoint hinting at expanding into remittances, FX and cross-border payments.

When startups adopt a geocentric or heliocentric perspective of product development, it tells us how their view of the market share they can take is changing.

Building geocentric products is a way of crowding in adjacent business models that will serve as tributaries and a moat in highly competitive environments. A heliocentric approach indicates the company believes it is better served by having largely independent products that each tackle a separate part of a large industry vertical. A payment fintech that houses an insurance group, a retail investment subsidiary, and a remittance product is a good way to visualise heliocentric businesses. In this instance, the company may be trying to build a business with products that tackle multiple parts of the financial services industry.

Perspective changes with time and place

Geocentricity or heliocentricity may work well in limited geographies. But this perspective and the localised success also makes it easier to miss the complex and external dependencies that make either approach work locally. And as companies grow they often begin to nurture the ambition to take their locally successful geocentric or heliocentric businesses to other markets.

It is often a recipe for mistakes because successful local geocentric or heliocentric businesses miss the fact that perspective changes with time and place.

For most of history, the universe was a plane around which the sun, moon, stars and planets revolved. It was what the farmhand and emperor observed. Ptolemy and Aristotle believed and taught this, and it became how many people in recorded history learned to understand the world they lived in and imagine the one they didn’t live in daily.

The ancient Greeks imagined the universe as a series of shells with a planet embedded in each layer. Arab astronomers calculated the total radius of the universe (from the centre of the earth to the fixed stars) to be 90 million miles. This was the commonsense scale of the universe until the fresh ideas of an old Polish clergyman and astronomer began to catch on eighteen centuries after a Greek mathematician first presented a model of the universe that placed the sun at the centre with the earth in orbit.

Today, we know that the universe is much larger than Nicolaus Copernicus (the Polish polymath clergyman) or Aristarchus of Samos (the Greek mathematician) even thought possible, as revolutionary as their theses were in their time. And we know this thanks to the advances in technology, mathematics, and physics that have broadened our perspective of the universe. We now know that we cannot know how big the universe is today; we can only estimate the size of the observable universe.

Next Wave continues after this ad.

But What does an essay about technology businesses in Africa have to do with ancient astronomy or the size of the universe?

Africa’s leading technology businesses are now quickly growing through geocentric and heliocentric perspectives of what scale means for them. This comes with all the chaos and missteps you can expect from anyone who navigates fluid systems.

Ptolemy, the ancient philosopher and mathematician, was mistaken in his assumptions about the state of the universe relative to Earth. To resolve the conflict, he attempted to create increasingly complex epicycles and eccentric models to explain the variations from his simple Everything-circles-the-earth theory.

Similarly, startups might make the same mistake and fall into the Relativity Trap as they shuffle perspectives of scale.

When startups reach a certain size everything seems ready for the taking and the possibilities are endless; it can begin to feel like if you can reach for it you can get it.

Occasionally, some startups do, while others fail spectacularly or retreat with painful bruises. It is at this stage that startups begin to commit to building a geocentric business by adding feeder products as they scale. Or choosing to create a heliocentric “ecosystem” of connected business lines.

Commonsense does not scale

In a localised environment, software businesses like Mpesa and WeChat may do very well geocentrically or heliocentrically. So it might be commonsense to build detached but related products around the firm’s core product. Or to grow a “solar system” of loosely coupled solutions that orbit a central (and typically attractive) problem, cultural pattern and/or societal design.

But the universe defies common sense. When a locally successful geocentric or heliocentric product begins to expand geographically, it will need to deal with a broader surface area where the things that were common in its stomping grounds are less so.

Next Wave continues after this ad.

Thus, Mpesa can build remittance rails for its home user market. But its historic struggles outside of Kenya suggests that the geocentric approach of building a world that revolves around its mobile wallet is a poor model for understanding the world of financial services outside Kenya. It’s the same for the many examples of failed product and/or company expansions and bruised retreat stories that we have seen in the last year.

When tech businesses begin to expand beyond their home turf, they soon discover that finding scale by building tribute products that are loosely attached to a core offering or building fully detached systems that merely orbit a “star” product is not enough.

Eventually, we may realise that the true universal relationships of technology businesses that will hold the stakes in Africa’s multi-billion dollar digital economy is not geocentric or heliocentric. Instead, we may well find out like the ancient astronomers that being geocentric or heliocentric is a perspective that will work well within localised context, but break once it transcends borders (geographic and otherwise).

Realising this should be a call to action for everyone with a stake in the success of Africa’s fledgling $180 billion hopeful internet economy to build better definitions and support for scale. Being geocentric or heliocentric companies is not an indicator of success; it is merely a perspective for assessing the market opportunity a business is trying to solve.

The important thing is not to lose sight of the fact that the universe of market opportunities is bigger than any one perspective and being nimble enough to steer the business, invest and support scaling companies accordingly. Scott Walker of Systemic Innovation and I put together a first draft at why this is too important to leave to chance. Read: Understanding, Defining, and Better Supporting High-Growth Scaling Ventures in Africa

Abraham Augustine

Abraham is a digital economy researcher and analyst based in Kigali, Rwanda. He leads Aperçu, a digital economy research lab and consulting group, and serves as Comms and Programs Lead at Norrsken East Africa. Read more from him on Money Myths Africa.

We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading today’s Next Wave. Please share. Or subscribe if someone shared it to you here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

As always feel free to email a reply or response to this essay. I enjoy reading those emails a lot.

TC Daily newsletter is out daily (Mon – Fri) brief of all the technology and business stories you need to know. Get it in your inbox each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.