For residents in Akiode, a community used to no electricity, 22 hours of electricity daily has worsened their quality of life.

Every night, residents of a 20-unit, one-bedroom apartment building in Akiode, a community in Ojodu, Lagos, pool money to buy electricity units. Their daily contributions, typically not more than ₦2,000 ($1.30), allow them to power essential appliances like freezers and fans, providing some relief on hot Lagos nights.

But the units are exhausted by 5 a.m. the following day, and the apartments are plunged into darkness.

It’s not a difficult adjustment; Akiode is accustomed to life without electricity. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, families endured three months of a prolonged power outage, and only a few families in Akiode could afford to fuel generators.

The darkness remains, but the cause is now a significant electricity tariff hike.

In April 2024, the Nigerian government approved a threefold increase in electricity tariffs as it struggled under the weight of a ₦700 billion ($451 million) annual electricity subsidy. The tariff hike created different customer bands, with Band A customers paying ₦225 per kilowatt for at least 20 hours of daily electricity.

“Before Band A, five of us shared one meter and we contributed around ₦10,000 or ₦15,000, and it lasted the whole month,” said Mr. Blessing, who runs a busy beer parlour. “Now, we’re recharging daily or weekly. Sometimes, we spend ₦10,000 in one week. That’s money we used to spend on food. We can’t afford three meals a day anymore.”

Band A was designed for affluent neighbourhoods and commercial areas, as these communities offered Nigeria’s eleven privately owned electricity distribution companies (Discos) the most reliable source of revenue. It allowed the Discos—which collectively lost ₦2 trillion ($1.2 billion) in six years—to offer reliable electricity at a premium to these communities willing to pay more. Since April 2024, Discos’ revenues have jumped by over ₦60 billion ($38.7 million).

Low-income communities, like Akiode, have been moved to Band A not because of the residents’ financial capacity but because of the technicalities of how feeders—power lines that transmit electricity from a substation to specific areas—are classified. Chinedu Amah, the founder of Spark Nigeria, a company providing clean energy solutions, told TechCabal that feeders are assigned to Band A based on their ability to deliver at least 20 hours of power daily, meeting the service-quality standards required for the higher tariff.

Across Nigeria, many of these communities have demanded to be removed from Band A as they struggle with the worst cost-of-living crisis in a generation. According to the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, 62.4% of households cannot afford enough food daily, with 12.3% reporting that at least one family member went an entire day without eating. In communities where those households live, the impact of the Band A tariff has been felt the most.

“Akiode isn’t the best place for Band A. The people living here would rather buy food than light,” said Toyin, a tailor who lives in a one-bedroom apartment.

A day before Band A was introduced, Toyin’s building bought ₦30,000 worth of electricity units. Three days later, on Saturday morning, the units had run out. The ensuing fight among her neighbours led to months without contributions and left the building in darkness. Since then, the neighbours now contribute ₦1,000 worth of electricity daily.

“Before Band A, I could work comfortably from home. Now I can’t,” Toyin said, reflecting on the changes since April. “I can’t buy much food because my freezer doesn’t work properly, so I only buy small quantities that won’t spoil. We also wake up at night to iron clothes or blend pepper for the next day, disturbing our sleep. Spending money on electricity daily also adds stress.”

Akiode is home to several shops selling essentials like medicine and food. While some shopowners have struggled to run their businesses, Mr. Bello, a former engineer who runs a frozen food shop, adapted to the Band A tariff by installing a separate meter for his business. An electricity meter costs either ₦119,000 ($77) or ₦218,000 ($141), depending on the load on the meter.

In the dim light of his office, his investment in expensive energy-saving appliances—low-power fans, inverter-compatible freezers—has helped him pay less for power than he paid before April. “I used to spend about ₦45,000 to ₦50,000 monthly on fuelling my generator plus ₦5,000 for electricity, totalling about ₦60,000 a month. Now, I spend roughly ₦15,000 a month,” he said.

Though his shop now enjoys reliable electricity, he’s mindful of the strain on families. “People are learning to manage power, but it’s hard. Appliances that once made life easier have now become luxuries.”

Matthew, another local tailor, has faced significant challenges since the tariff increase. “I share a meter with 10 other people,” he said. “Before Band A, I spent ₦3,000 a month on electricity. Now, I’m paying ₦12,000 monthly. It’s not affordable, but I have no choice if I want my business to survive.”

Despite Matthew’s challenges, the demand for electricity remains inescapable; even in weeks when he does not make money. “If the building wants to buy light, I have to pay my share, even if I didn’t use electricity.”

The conflicts in Akiode are more than just financial. In some buildings, fights among neighbours escalate to frequent visits to the nearest police station, driven by frustration, as some tenants struggle to keep up with the daily payments.

As a workaround, some residents sharing electricity meters have found creative solutions to the Band A challenge. Many buildings now have small unit readers installed that show each flat’s electricity usage on a screen—a vital tool for easing the tensions Band A has sparked among neighbours.

Before Band A was introduced, Sarah, a resident using a unit reader, lived a different life. “I used to spend ₦3,000 a month running my freezer, TV, iron, and everything,” she said about her electricity contributions. “Now, I spend ₦15,000 and don’t even use my freezer anymore. Just the TV and a fan.”

Sarah now tracks her meter readings religiously, taking pictures before leaving home to ensure no extra unit is consumed in her absence. When ₦4,000 guarantees barely three days of electricity, you learn to be watchful.

She has also acted as a lender of last resort to some of her neighbours when they cannot afford their contributions. They lend her money in return, but sometimes the neighbours wait until everyone can contribute before paying for electricity.

In some buildings without willing lenders, payments are irregular, operating on a pro-rata basis. “Not everyone pays daily. Some pay today, others pay the next day. We just contribute as we can,” one female resident who asked not to be named said.

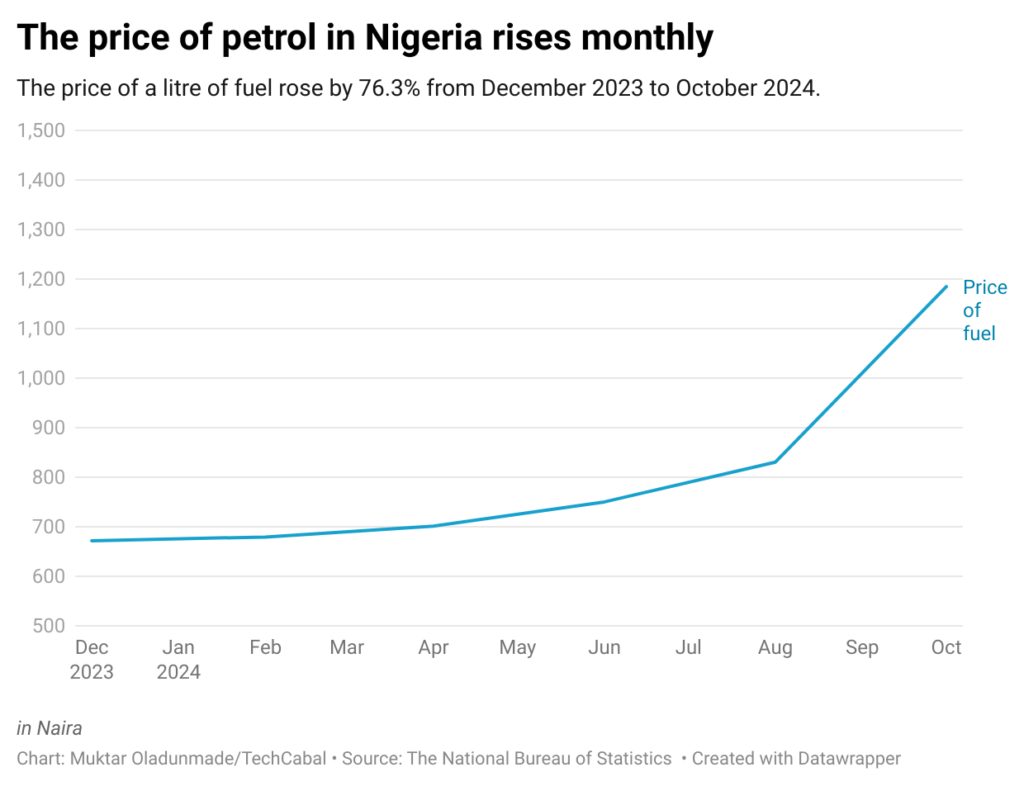

In 2023, some residents would have gladly resorted to fuelling noisy generators instead of paying for Band A or as substitutes whenever electricity units ran out. However, since fuel prices skyrocketed after President Bola Tinubu removed subsidies, that option is now out of reach.

With fuel costing ₦1,000 per litre or more, even the smallest generator would require ₦4,000 to fill its tank, making it expensive to maintain. It can only power light bulbs and small fans, struggling with heavier appliances like larger TVs or standard fans.

“Fuel is also expensive. You don’t know which option to take because both are costly. You’re stuck in the middle, not knowing what to do. Sometimes it feels like I’m suffering and smiling—laughing on the outside but dying inside,” Mr. Blessing said.

The option of solar panels and inverters, which can cost between ₦200,000 and ₦5 million, is also out of reach for several residents. “There’s no money for that,” Sarah said simply when the question of solar inverters was brought up.

For Iya Ghana, a roadside food seller, Band A has brought relief and frustration. “I like it,” she admitted. “At least we have light, and I don’t buy petrol for the generator anymore.”

But the cost is still steep. Every six days, she spends ₦9,000 to power her home and by the end of the month, she spends more than half of the national minimum wage on electricity.

The irony isn’t lost on her: Band A offers a service she prayed for—reliable electricity—but the price has threatened the survival of her neighbours and customers.

Still, she thinks the tariff should remain. “We’re benefiting from it. Some people might complain, but you can’t live in darkness. Light and water are essential.”

She’s not alone; at least five other residents feel Akiode should remain on Band A but with a reduced tariff.

Others argue that placing Akiode on Band A was a mistake and said it’s not too late to correct it. “The light is constant now, and we’re enjoying it, but that doesn’t mean we should sacrifice everything for electricity. I need to take care of myself too. What’s the point of having light when you’re hungry?”, Mr Blessing asked no one in particular.

Yet, amid the struggles, there’s a quiet determination to endure. Toyin remains hopeful. “We want to enjoy the light,” she says. “But the money is too much.”

“Nigerians adjust to any situation—that’s the problem,” Mr Ondo, a father of two, said with a mix of frustration and acceptance. “We complain, but nothing happens. If we protest, nobody listens. People are suffering and smiling. That’s the Nigerian way,” Mr Ondo said.

Like many Nigerians before him, he must adjust to a new reality, where his quality of life has declined in the past year.