Written by: Elizabeth Osunsanwo

When Nigeria’s NITDA proposed sweeping powers over the digital economy in late 2024, critics called it regulatory overreach. But look closer: Nigeria is attempting to rebuild the state itself using the logic of software.

This isn’t unique to Nigeria. Rwanda delivers over 100 public services through its Irembo platform. Kenya’s Huduma Namba aims to become the authentication layer for every government interaction. Senegal is building data centres to host government services locally, treating infrastructure sovereignty as seriously as territorial sovereignty.

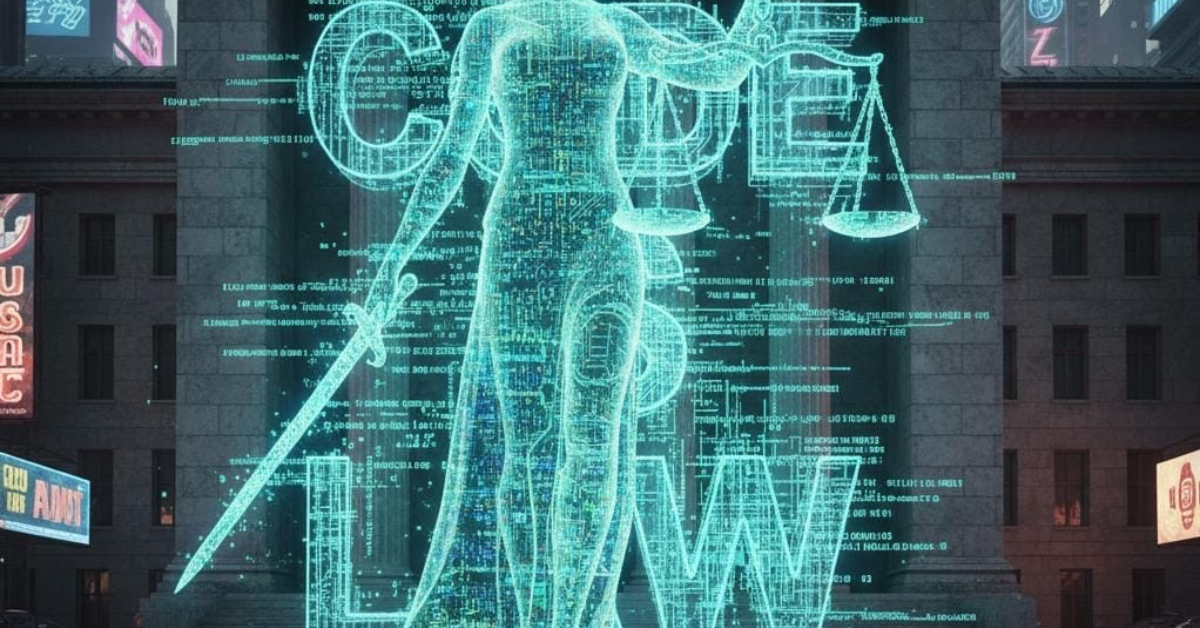

African states are learning to think less like bureaucracies and more like systems engineers. The question isn’t whether this transformation is happening. It’s whether we’re building systems that serve citizens or systems that encode the same old power structures in unbreakable code.

The software engineering playbook for government

Modularity becomes policy. Instead of every ministry building its own payment system, you build shared components. The promise is efficiency. The risk is that a single point of failure breaks everything.

Iteration replaces grand plans. Rwanda didn’t launch Irembo with 100 services on day one. They started small, fixed what broke, and gradually expanded. This agile approach works better than five-year master plans obsolete before implementation begins.

Open source as shared sovereignty. Why should every African country reinvent the same digital identity system? Governments still think in terms of national sovereignty, not collaborative development. Meanwhile, they’re all licensing expensive proprietary systems from Western vendors.

When code becomes the new bureaucracy

Code doesn’t just make things efficient. It makes power more durable.

Consider algorithmic welfare systems. Several African countries are exploring AI to decide who gets assistance. But if training data reflects historical bias, the system doesn’t eliminate discrimination—it automates it at scale and wraps it in the legitimacy of “data-driven decision-making.”

Nigeria’s National Social Register has excluded millions who should qualify. The criteria are opaque. Once an algorithm decides you’re not poor enough, challenging that decision is harder than arguing with a human bureaucrat.

Then there’s sovereignty. Most African digital infrastructure runs on foreign cloud providers. When citizen data lives on servers in Ireland or Virginia, what does digital sovereignty even mean? When tech giants train AI models on African data without permission, we’re not participating in the digital economy. We’re being mined for it.

The exclusion algorithm

Every digital system excludes someone. When Rwanda celebrated 95% of services being online, it also meant if you’re without internet, can’t afford a smartphone, or have low digital literacy, the government has effectively moved further away.

Digital by default becomes digital exclusion. When services go digital without offline alternatives, the most vulnerable citizens become invisible to systems that only “see” what’s in the database.

What should actually happen

Build African digital public goods, not 54 separate systems. We need continental infrastructure that countries can customise, not proprietary systems licensed from foreign vendors.

Treat data sovereignty seriously. We need regional cloud infrastructure, African-owned and governed, with clear legal frameworks.

Regulate AI before it regulates us. When an algorithm denies someone healthcare or assistance, they deserve to know why and have the power to challenge it.

Engineer for the Africa that exists. Not everyone has 5G. Most people don’t own smartphones. Any system that doesn’t account for this is exclusionary with better branding.

Make the code public. If governance is written in software, citizens deserve to read the source code.

Who writes the future?

Right now, most African digital government infrastructure is designed by foreign consulting firms, built by global tech companies, and hosted on foreign servers. The expertise is imported. The infrastructure is rented. The data flows outward.

Africa has software engineers and policy thinkers who understand both technology and context. What’s missing isn’t talent. It’s political will to invest in homegrown capacity and treat digital infrastructure as a public good.

The state of the future will be built with code. The question is whether that code serves justice, transparency, and human dignity, or whether it just makes old power structures run faster and hide better.

Every API is a policy decision. Every algorithm is a value judgment. Every database is a choice about who gets seen and who gets erased.

The only question that matters is: who gets to debug it when it breaks?

Elizabeth Osunsanwo is a full-stack software engineer and International Relations Scholar specialising in government technology systems and public sector digital transformation. She is currently researching how software engineering principles can improve governance in global contexts.