For our French readers…

In the past few weeks, Nigeria has been caught up in an election fever that reached a bubbling temperature yesterday and continues to trend. Six months ago, Kenya was in these same crosshairs. For both elections, business operations and dealmaking ground to a crawl, a searing reminder of how politics is deeply and weirdly embedded in the makeup of African economies. Ghana, Egypt, and South Africa are a few of the African elections we will witness next year. See a list of all of them here.

Elections have always happened in one place or another in Africa, so why are these elections important?

The answer is that Africa is overrepresented in the list of emerging markets facing or passing through severe economic crises—with more pain ahead. Here’s what the World Bank says.

The global economy is projected to grow by 1.7% in 2023 and 2.7% in 2024. The sharp downturn in growth is expected to be widespread, with forecasts in 2023 revised down for 95% of advanced economies and nearly 70% of emerging market and developing economies.

Over the next two years, per capita income growth in emerging market and developing economies is projected to average 2.8%—a full percentage point lower than the 2010-2019 average. In sub-Saharan Africa—which accounts for about 60% of the world’s extreme poor—growth in per capita income over 2023–24 is expected to average just 1.2%, a rate that could cause poverty rates to rise, not fall.

Excluding China, growth in emerging markets and developing economies is expected to decelerate from 3.8% in 2022 to 2.7% in 2023, reflecting significantly weaker external demand compounded by high inflation, currency depreciation, tighter financing conditions, and other domestic headwinds.

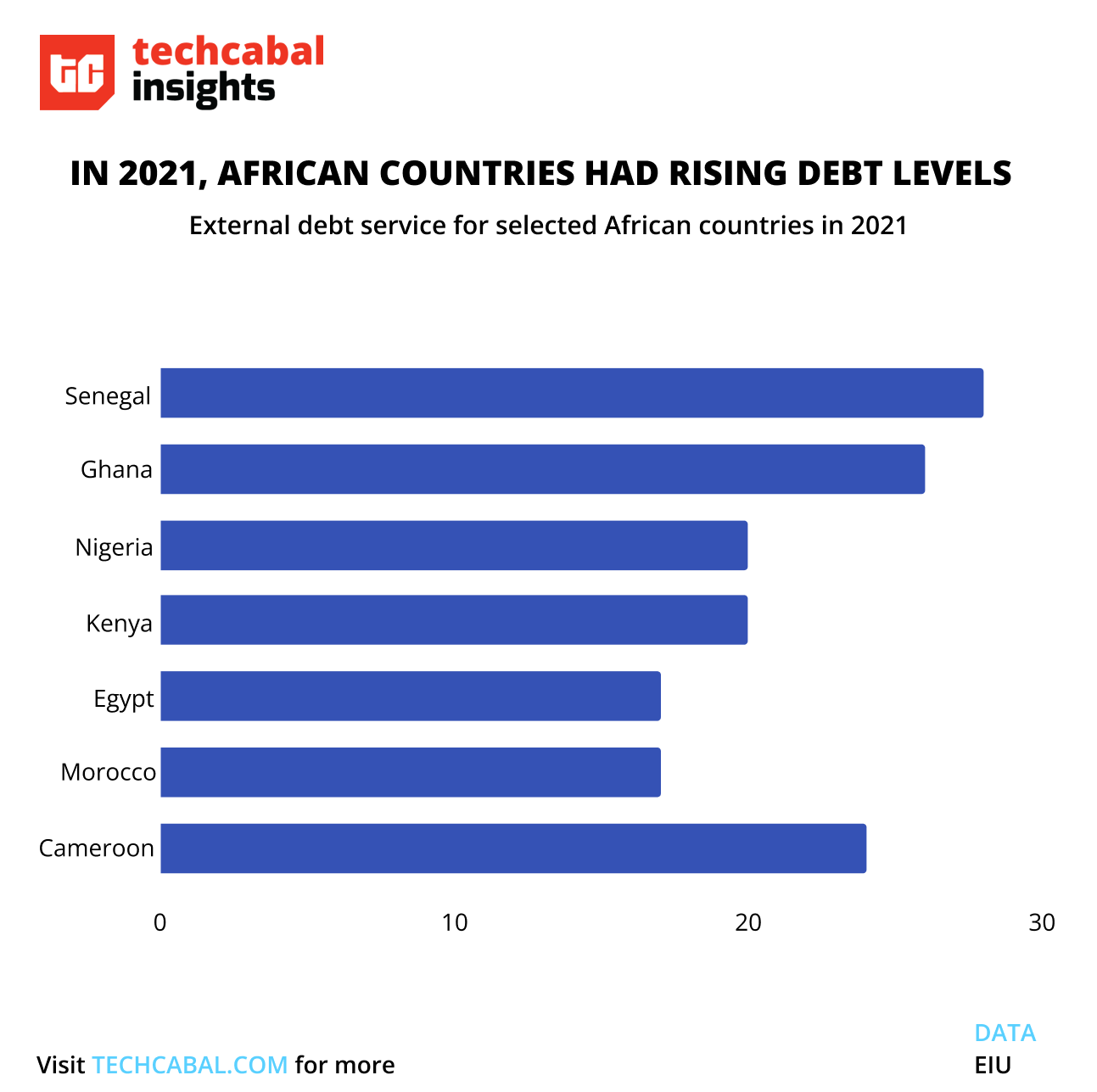

Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, notes that “about 15 percent of low-income countries are already in debt distress and an additional 45 percent are at high risk of debt distress. Among emerging markets, about 25 percent are at high risk and facing default-like borrowing spreads”. This has happened because governments have taken too much of the wrong type of debt. Debt combined with a volatile global situation forms a self-perpetuating debt loop.

African countries, from Nigeria to Egypt, are susceptible to rising debt levels amid dwindling revenues. | Chart by Ayomide Agbaje — TechCabal Insights

Investors of all kinds pay attention to how these domestic headwinds develop in order to determine if their portfolio should expect rainstorms or a full-blown cyclone. For technology investors and entrepreneurs in Africa where foreign capital still does the heavy lifting, especially for mid-stage deals, these economic conditions are scary and tend to coalesce into simple narratives of emerging market bad, or emerging market buy. Depending on who you are listening to. But there is more nuance to the story. For already invested firms or people planning to invest, you cannot afford to miss these nuances.

Elections complicate things

The first lesson is that elections will make tricky regulatory environments more touchy, not in response to startup behaviour, but in response to political needs and often without regard to good economic sense.

Weeks before the Kenya presidential polls where he supported Raila Odinga over his deputy, William Ruto, former president Uhuru Kenyatta bowed to pressure and reintroduced subsidies on unga (maize flour), a staple in Kenyan households. Weeks before Nigeria’s elections, President Muhammadu Buhari and the country’s central bank enforced a poorly designed and implemented currency demonetisation programme that continues to wreak havoc on payment transactions (or boost digital payments, depending on who you ask). Similarly, South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa, who hopes to lead a divided African National Congress (ANC) to the May 2023 polls, is failing to fix South Africa’s power debacle. It is believed he is playing it safe with his political allies, making strategic compromises along the way. Both South Africa and Nigeria were grey-listed as sources for illicit funds transfer and terrorism financing by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) last week.

Elections in Africa have consequences that even precede the votes being cast. Your investment strategy must recognise this painful fact and it should inform how you support your portcos even before the elections!

The king dollar index is your friend

Ruurd Brouwer, the chief executive of TCX, a currency hedging fund set up by several development banks to help developing countries ameliorate FX risks, writes.

While many big developing countries have developed domestic bond markets—mitigating the risk of original sin—the foreign-currency share of the debts of low-income countries is around 70–85 percent, according to UNCTAD. When the currencies of developing countries fall—as they generally have against the dollar in recent years—the burden of these debts increases commensurately.

As the currencies of countries that participated in the DSSI depreciated 22.5 percent on average against the US greenback, every dollar of debt suspended has now in practice turned into $1.225 of debt in local-currency terms. And it’s the local currency that is relevant for borrowers, given that the vast majority of their revenues will be domestic taxes. As a result, the non-participants had a better deal in debt terms.

Now, what does all this mean in practice? Let’s take Ethiopia, a good example as they were hit the hardest.

The country got a $800mn payment holiday, but the fall of the Ethiopian birr increased the effective burden of their debts by 35 percent over 2020–22. In US dollar terms, that is an increase of $9.7bn (conservatively recalculating using 2021 exchange rates).

Zambia got $700mn of relief, yet the depreciating kwacha led to a debt burden increase of $1.7bn. The effective weight of Kyrgyzstan’s debts grew by more than five times the amount suspended; $120mn versus $660mn.

The king dollar index is the measure of the relative strength of the dollar to the local currencies an investor or operator is invested in. The point is not to run away because of a depreciating currency (currencies are fickle, especially in emerging market currencies). The point is that sophisticated investors will realise how much this matters and work with entrepreneurs to mitigate (and even find opportunities to benefit) from the USD index. Admittedly the opportunities for doing this in venture capital investing are slim, but the awareness also helps if nothing else, for helping to manage expectations.

The informal is your market

In December last year, Egyptian prime minister, Mostafa Madbouly, asked the country’s Ministry of Supply and Internal Trade to open the Ahlan Ramadan fair by January 1, 2023 until the end of the holy month of Ramadan. Ahlan Ramadan are markets that sell cheap groceries during the Ramadan fast. Inflation-stricken Egyptians are flocking to Ahlan markets already presenting competition to grocery startups and highlighting a deepening in the informal food supply space.

When economies grow worse, people go informal. In an election year that is beset with tight economic realities, this cocktail will only be worse. Investors and entrepreneurs in our innovation space will thus be building more resilience by treating the informal as a primary space.

We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

Abraham Augustine,

Senior Writer, TechCabal.