Editor’s note: For the best viewing experience, click the half-moon icon ☾ at the top right of the page to switch to dark mode.

Sanusi Ismaila moved from Lagos to Kaduna in 2014 to set up a technology hub that trained people to solve real-world problems. He believed it was essential to inspire and cultivate tech ecosystems outside of Lagos because local issues need to be solved by locals who understand the nuances.

After a while, he ran into his first problem: no talent pipeline to sustain startups nationwide. So, he went one step backward on the value chain to produce the talent needed to build high-quality products and startups.

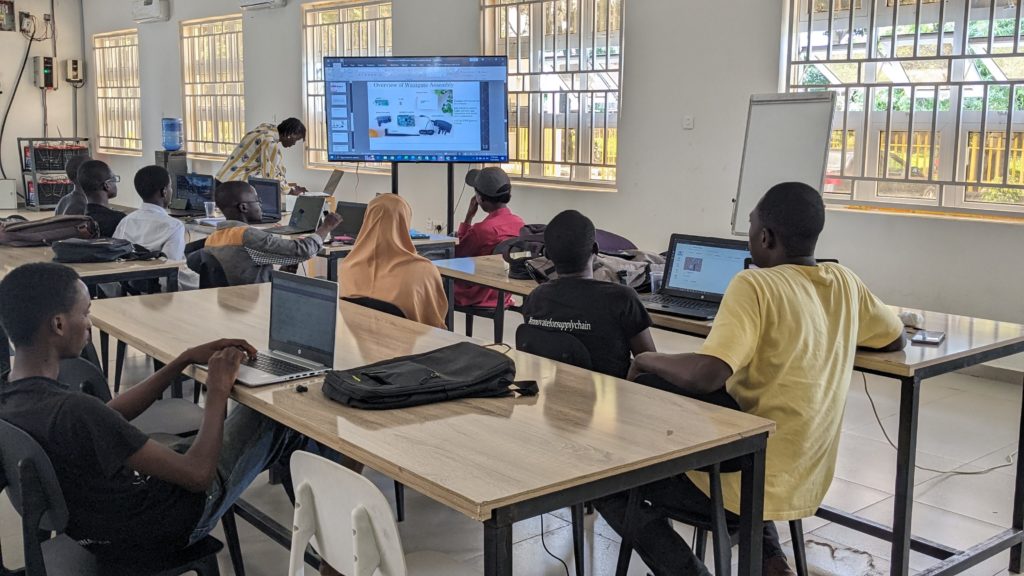

In 2016, Ismaila launched CoLab, and it became Kaduna’s first tech hub and the second in northern Nigeria. Today, CoLab is a community for those building tech careers and dreamers looking to connect and learn from each other.

Lagos is to the Nigerian tech ecosystem what Silicon Valley is to the North American ecosystem. Yet, unlike the United States, where other states like New York, Seattle and Chicago still have thriving ecosystems that complement Silicon Valley, tech ecosystems outside Lagos struggle to build their identities or grab significant attention from stakeholders. As a result, some of the best tech talents from these regions frequently feel the need to migrate to more viable regions to attract better opportunities.

On a sunny afternoon in 2018, Pablo watched two young men walk into the barbershop wearing hoodies with CoLab and Python inscriptions. He had previously attempted to learn data analytics but gave up due to what he describes as a “lack of understanding.”

After a brief conversation with these men, he discovered they were CoLab members; the following month, he signed up to learn data analytics. Six years on, he now works at AltSchool and is the director of people and head of data science programs at CoLab while still living in Kaduna.

What started as a small community of young people wearing hoodies and sitting around with used HP laptops has become one of northern Nigeria’s biggest tech talent pipelines. CoLab has over a thousand alumni, with some collaborating to build startups like Sudo Africa and others working in organisations like Paystack, Microsoft, and Google.

The community became such a force that in May 2022, the Kaduna State Governor, Nasir ElRufai, provided them with seven hectares of land to set up a campus and train even more tech talents.

Excel Ajah, who built writersgig, an online platform for freelance writers, has struggled with finding tech talent, and he believes that this is a significant contributing factor to the slow growth of the tech ecosystems in the East.

“Because ecosystems like Lagos are more advanced, it’s easier to find people who can do exactly what you want,” he shared.

The tech ecosystem in Imo State is in its earliest stages and didn’t begin to take shape until 2020. According to Ajah, its inception can be traced to when he and a couple of people started hanging out in public facilities to work and discuss other tech ecosystems like Lagos. In no time, they attempted to replicate these communities and events they saw in Lagos and soon organised The Owerri Business Week and Social Media Fest, which attracted a lot of attention and have become annual events.

While still running writersgig, Ajah launched Silicon Africa, a tech innovation centre dubbed after its counterpart in San Francisco. With a new company came hiring needs, which was where he encountered his first challenge. Scarcity of talent. It was difficult for Ajah to find strong developers in the region to work for his company, so he began training them instead.

“Some of the early developers I hired still work with me and are now senior developers who now train other early-stage developers in the centre,” he shared. “This has been interesting to watch because it has become a cycle, and those they train now train others.”

For Chidi Duru, another founder who operates from Owerri, the problem of the ecosystem in Imo precedes a scarcity of talent. For him, it’s a lack of interest in learning tech skills driven by the popularity of internet fraud in the region, especially in the past years. Duru’s tech hub, CodeAnt, provides coding classes to young people with support from Google, but it is still difficult to convince young people to focus on learning tech skills.

“Young boys still in their teens have latched onto the idea of internet fraud being what tech represents,” he shared. “As soon as you mention tech in a lot of places here, people think you mean a way to make quick money, and when they learn that it takes time, they automatically lose interest.”

As a founder, building from Owerri limits him from a network of people who understand what he’s building. Recently, in Lagos, he walked around at a centre wearing a CodeAnt hoodie merch and had a couple walk up to him to discuss the classes and company.

“This has never happened in all the years I’ve been wearing our merch in Owerri,” he shared while laughing. “I even contemplated moving to Lagos for some minutes.”

While it’s a lot of work, Duru says that he’s committed to putting in the work to ensure that aspiring tech talents in Owerri have a space that’s dedicated to their growth and learning. So far, they’ve trained about a thousand young people with coding and digital marketing skills.

Beyond a talent pipeline, Lagos has a more structured ecosystem that encompasses the talent, the investors to fund these ideas, and the media to tell stories about said ideas. In newer ecosystems like Imo, for example, securing avenues to tell their stories on the centre stage can be difficult. Most tech media is focused on more vibrant ecosystems like Lagos, which makes getting their attention “a bit challenging,” in the words of Duru.

During a fireside chat in January, Sim Shagaya, the founder of u-lesson and Miva, both Abuja-based ed techs, shared that one of the reasons why tech ecosystems outside Lagos have struggled is a lack of structured institutions in these regions. Before the rise of the tech industry in Lagos, it was already home to tertiary institutions like The University of Lagos, Lagos State University other private and open universities, providing it with a high mass of young people from these institutions to feed into the tech ecosystems.

This population, which is a blessing in this case, could be its blight. Pablo believes that smaller ecosystems are the best place to learn and get into the tech space as they offer the intimacy of organic communities.

“It’s more difficult to find organic communities in a place as fast-paced as Lagos now. In smaller, growing ecosystems, you can walk in and speak to whomever you need to because people are more open and willing to share.”

According to Pablo, the tech ecosystem in Kaduna isn’t trying to be like Lagos. The more conservative state has a culture and rhythm that is slower and smaller compared to Lagos, and he doesn’t think that will change anytime soon, as it works perfectly for the people operating in the region.

“It gives participants a chance to build without a lot of noise and pressure, which is especially important for people in the early stages,” he shared over a call. “ People do not feel the need to perform for a large ecosystem, and there’s a lot more space to interact in communities and gain access to the things you need as there’s less competition.”