Tim Berners-Lee first drafted a proposal for the “WorldWideWeb” in 1989. Titled “Information Management: A Proposal” and presented at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, where he worked at the time, the proposal had met with “minimal internal interest”. That proposal would revolutionise how information was spread and consumed. His hypertext link-based information management system was going to make it possible to retrieve information (identified by a Uniform Resource Locator, or URL) from a large database using an application called a web browser and made accessible by the internet (not to be confused with the web.) The ideology behind his proposal was the need to create an open, easily accessible vault of information for everyone, anywhere in the world, to collaborate and learn and advance for good. And rightly so.

The web had just begun to bloom around the time I was born. By the time I started a blog in 2017, I learnt all I knew about building and managing a WordPress site from a myriad of webpages that turned up in lots of Google searches. The web opened up access to information and an era of digital revolution that has morphed into a number of things. We can learn anything outside the four walls of a classroom; the news is right there at the swipe of a screen; we have little or no use for letters and post offices anymore; we can meet and work with people whom we have never met, support a cause or rally for policy change; make calls to a loved one a thousand miles away via computer; make hospital visits from our living rooms and a whole lot more.

But, just as the web opened up these wealth of experiences to us, it also brought with it a kind of Pandora’s box that its founder had not envisioned at the time of its creation.

In 2014, Cambridge Analytica, a subsidiary of now defunct behavioural research company, SCL Group, begun to collect data and information from Facebook users using a quiz app called thisisyourdigitallife. They used the information users provided to build a system that could profile individual voters in the United States in order to target them with personalised political advertisements. The organisation was headed by then presidential candidate, Donald Trump’s key adviser, Steve Banon. Users were told the responses to a personality test on the app was for research purposes.

“They collected data for research purposes and didn’t use it for research purposes,” Tim tells me on the rooftop of the Co-Creation Hub in Yaba, Lagos. He has arrived for the completion of a 30-hour trip from Geneva through London in celebration of the World Wide Web at 30.

What culminated is now being referred to as one of the biggest data breaches in recent times involving information from over 80 million Facebook users.

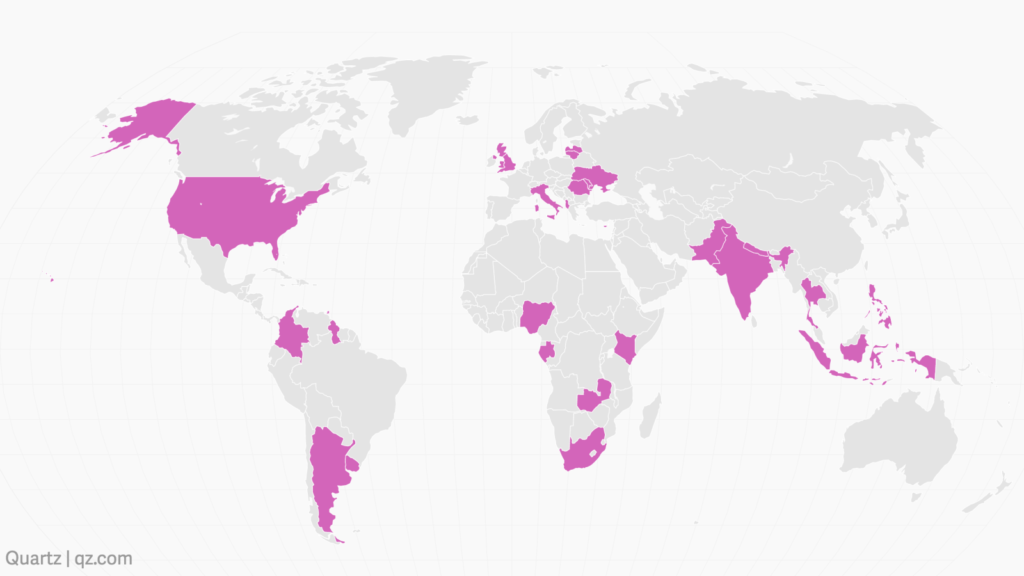

A map showing SCL Group’s global reach.

Source: Quartz

“Fake news started because the economy of the web is an economy of numbers,” says Nnenna Nwakanma, Interim Policy Director of the World Wide Web Foundation.

“When people found out that the more people visiting your platform the more economically viable it was, the new method became – what do you do to get people to click and visit your website.”

And so, while the internet continues to serve as a repository for information of all kinds, it has also become a source for gross misinformation, a vehicle to drive propaganda and perpetuate falsehood. Nigeria, for instance, continues to stand on the precarious balance of religion, politics and ethnicity and the proliferation of fake news has done nothing to balance this stance. In September 2017, the presidency had reported that a fake speech of President Muhammadu Buhari was going around on social media even before the President arrived in New York for the 72nd session of the United Nation General Assembly meeting. In December last year, a wildly viral news article reported that President Buhari had been replaced by a Sudanese clone named Jubril, fostering fear that the country was in incompetent hands. In India, gross misinformation and fallacies spread through chat platform WhatsApp has resulted in lynchings and hysteria over child kidnappings and discouraged parents from vaccinating their children.

While half the world is now online, women are 12% less likely to use the internet globally than men, while in low and middle-income countries, the gap between women’s use and that of men is 26%. Yet, in many places, issues of affordability, access and infrastructure mean that for those yet to come online, the hurdles to scale to bridge the gap is widening. Online bullying, internet shutdowns by governments across the globe and hate speeches have become some of the most dire outcomes of the web that Tim, under the auspices of the World Wide Web Foundation, which he founded in 2009, is hoping to fix.

Digital penetration around the world in 2019

Source: We Are Social

At the core of this migration back to what was originally intended for the web is the way that data and information is controlled. Who handles what? How much autonomy do the owners of the data have? And how can they determine what truly happens to their data as they navigate millions of web pages across the internet leaving bits and pieces of their information?

Tim has created an open-source platform called Solid (Socially Linked Data) which he hopes will remedy this problem. Solid is designed to allow individuals and organisations store their data in PODS (personal online data stores) which can either be self-hosted or stored publicly in a cloud. Ultimately, apps only have access to a POD when an owner grants them access to it. Developers can also create apps on the platform “without harvesting massive amounts of data first”. Last year, Solid opened up its platform to developers to build apps on it through another platform, Inrupt, which he created to help fuel the growth of Solid.

“We turned it on, on a Friday I think, and over the weekend, we ended up with something like 20,000 people signed up on each of the two sites,” Tim says. And the community is rapidly growing.

In this digital economy of numbers and data, taking users’ data from the tech companies who currently enjoy the commercial benefits of their monopoly over it will be a Herculean task. So asides, Solid/Inrupt, the Web Foundation is looking to draw up what it’s calling the Contract for the Web, a comprehensive document which it hopes will be created by and guide, moving forward, individuals, governments and organisations in their use of and conduct on the web.

The Contract for the Web hopes to take the web back to fulfilling its founding vision

Source: Pexels

Launched in Lisbon at the 2018 Web Summit, over 200 organisations (including Google and Facebook), government bodies and individuals have signed the contract. With the contract, Tim wants everyone to rally around governments and organisations to ensure everyone can connect to the internet, access every aspect of it, develop technologies that bring out the best of humanity and have their privacy respected. The contract will also compel individuals to collaborate and create online, provide a safe and welcoming space for the next user, and fight to make the web a useful tool. Currently, working groups have been created and almost everyone who has volunteered or joined in the campaign are now working on specific issues the contract hopes to address.

“The idea is that before the end of this calendar year, there should be some sort of report indicating where the people who sat around the tables came from, and what they thought about where the interface between technology and policy should be,” Tim says.

“I don’t know which way we’ll go because I don’t know if we’ll be able to focus and iron out all the bumps,” Tim says when I ask what he hopes will happen with the web in another 30 years.

But he is of the opinion that the future of the web is what we try to make it, for ourselves.

“We should not imagine that this is something that has been predestined.”

Featured Image: Wikimedia Commons