TC Regulate expounds the laws, regulations, policies, best practices, and compliance, with respect to tech and innovation in Africa. Our expert contributor network will help you understand the policies, their impact and how regulators and other stakeholders can capture real value in the tech-age.

—

With the surge of VC investments in Africa, some investment practices seem to have become the norm at least in anglophone African countries.

On the other hand, many investors are unable to invest in francophone Africa because of language and business barriers.

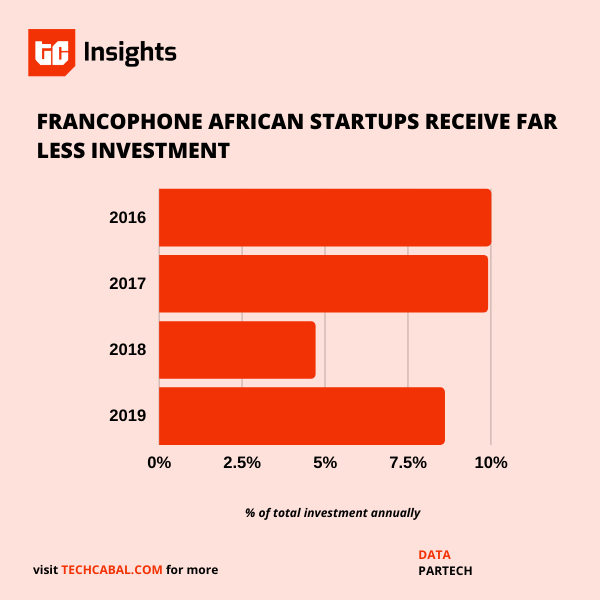

The share of African venture capital money invested in francophone African startups is small compared to other regions and continues to drop.

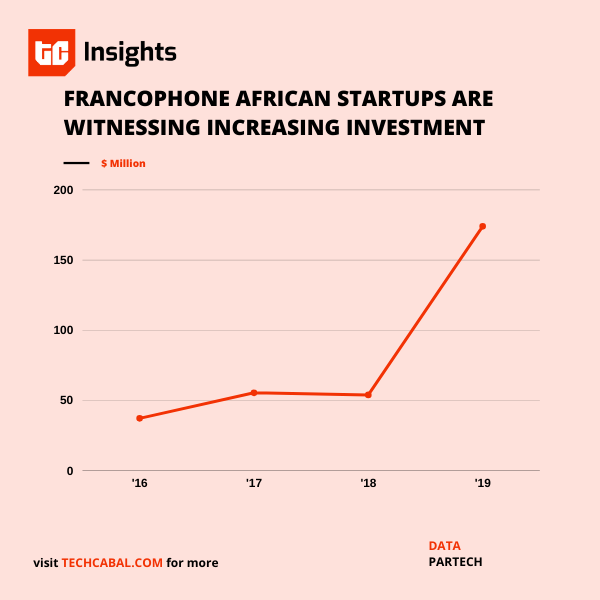

However, over the past four years, there has been an increase in the value of money going to the francophone region.

As investors and entrepreneurs in their search for new opportunities start to look at francophone Africa, it is crucial to be aware of certain peculiarities of francophone African markets.

The francophone business law system presents the advantage of being very unified, insofar as there is one set of corporate rules that applies to 17 countries, and they share the same highest court. One must however note that most business concepts that can be easily used in countries like Nigeria and Kenya, cannot be implemented without certain key adjustments when going to francophone countries. Below are two examples of this difference:

The first illustration relates to the most common form of companies used in francophone Africa – the société par actions simplifiée (“SAS”) – the joint stock company. This form of company was introduced in 2014 and in my estimate, more than 60% of the start-up ecosystem in francophone Africa are SAS.

The success of this vehicle can be explained by its contractual flexibility, as well as the ease of incorporating such vehicle (no need of a public notary nor minimum capital – contrary to most other legal forms).

There is however one important point that any financial investor should note before investing in such vehicles: the rules applicable to SAS provide that in certain circumstances, departing shareholders will remain liable towards other shareholders and third parties for a period of five years for the liabilities existing at the time of his/her withdrawal.

They are to be held liable for up to the amount repaid to the departing shareholder at any time up to the date of his/her withdrawal.

This provision can rightfully create some concerns for financial investors keen to get a clean exit when they transfer their shares in companies through secondary sales or otherwise. Fortunately, it is possible to work around this issue, but it is however important to be aware of its existence.

The second example relates to SAFE as an investment instrument. While SAFE agreements are old news in the anglophone VC, they are relatively new in francophone Africa and make for another example of how anglophone concepts have to be adjusted before being applied to francophone markets.

It is to be noted that the current francophone corporate rules as they apply in sub-saharan francophone markets do not allow SAFE instruments to be entered into by private limited companies. Note that private limited companies are the second most popular form of structure after the above mentioned SAS.

This means in practice that in order to enter into a SAFE agreement, a company based in francophone Africa may have to be established as a joint stock company bringing with it the issues of lingering liability described above, or go for a much burdensome legal structure.

In conclusion, while the markets may be geographically close, there are potentially significant differences that investors should be aware of when making investments in francophone Africa.

Editor’s Note: Johanna Monthé, is a lawyer qualified to practice in England and Wales, Paris, New York and Cameroon. She is a partner at the law firm Epena Law, and specialises in private equity, venture capital and regulations in Africa. She is based between Lagos and Douala.