Continental open data incubator Code for Africa is using publicly available data to help Kenyans find voter registration centres so that they can ensure they are eligible to vote in the 2017 general election.

Got to Vote! Kenya was built as a Code for Kenya data journalism project to demonstrate how data-driven tools can help ordinary citizens engage more effectively in the political processes happening around them.

With one week left, the month-long registration exercise has been characterized by low voter turnout, with the country’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission noting that part of the problem is a general lack of awareness on the location of these registration centers.

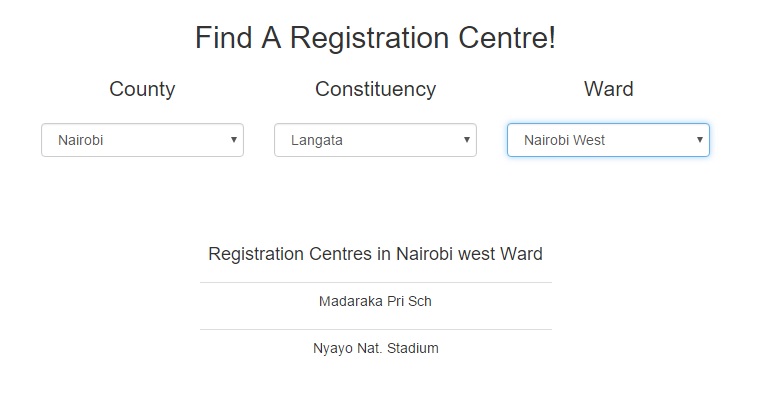

The Got to Vote database contains a list of all 47 counties, the 290 constituencies arranged by county, and wards, with the polling stations in each ward listed alphabetically. Those wishing to register can look for the station closest to them.

The Got To Vote website also contains some basic voter education information. It gives an overview of the registration process, explaining who is eligible to register and the necessary documentation.

GotToVote! was built as a Code for Kenya data journalism project to demonstrate how data-driven tools can help ordinary citizens engage more effectively in the political processes happening around them.

The information on voter registration centers is publicly available, but only as difficult-to-access PDF and MS Word or Excel documents hosted piecemeal by the Ministry of Information, the Electoral and Boundaries Commission and a variety of different Government websites.

Two Code for Kenya fellows, David Lemayian and Simeon Oriko, scraped the data and built a simple website for citizens to find their registration centre at the click of a button. The website also helped citizens understand the often complex procedures for registering.

The first version of GotToVote was built in just 24hrs, at zero cost. Code for Kenya initiated the project following complaints that the official data released in by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) was too bulky to download on the fly and too cumbersome to use.

“The file was huge. It was a complicated mess of lists and tables of constituency registration centres. These elections are a tight race, and every vote counts. So, we knew that the information was simply too important to be ignored,” explains Open Institute executive director, Jay Bhalla.

The second phase of the project, cleaning up and compiling the data, took three days and cost US$500 to execute. All the cleaned-up data and source materials used to power this website are available, free-of-charge for re-use here. The source code for the project is also publicly available here.

The project received funding from HiVOS East Africa to build additional functionality and package GotToVote and other useful civic technology tools into a resource kit for media and citizen groups in other countries.

Once voter registration is complete, the site will be repurposed to share official election results from the counties and constituencies. GotToVote will also contextualise the results, by overlaying ballot returns with information about local trends, and official reports of local election fraud or other irregularities.

“The media and political parties are all focused on the national results and on results affecting two or three of the higher profile presidential contenders. The ordinary citizen and their need to know about their local results was getting lost in all the hype. GotToVote seeks to change that, by giving citizens their local results, as soon as they’re available, and mashing up these results with other locally relevant data,” says Bhalla.

GotToVote! has since been replicated in Malawi, where electoral authorities adopted it as the official government solution for voter verification. It has also found use in elections in Ghana, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

“GotToVote proved that the real power of civic technologies is their ability to quickly and cheaply translate complex data into actionable information, and to then calibrate the information to a citizens’ exact location or other circumstances,” says Code for Africa Director, Justin Arenstein.

Future versions of the site will introduce SMS tools, and will help users verify their registration, find their balloting stations, and track their local election results.