Before I moved to Lagos, I had spent over two decades growing up in the coal city, eating breakfasts of ọkpa (and accompanying bowls of custard or pap), suffering the crackling dryness of harmattan and enduring the red-earthed muddiness of the rainy season. I disliked the pace. I always thought it too laid-back. Too sluggish. It was unlike the aggressiveness and urgency that I would come to know with living in Lagos.

I remember the first time I visited Lagos. I arrived sometime before midnight and was startled by the activities that greeted me at the Ikeja Bridge as I made my way to a relative’s at Allen Avenue, a short way off. It baffled me to see that as late as it was, shop owners went about their businesses showing no sign of readiness to go home.

I think my wide-eyedness could be excused. I was afterall coming from Enugu, in south-east Nigeria, where you can set out for an engagement minutes before it begins and still make it with time to spare. Not only are there extensive bus and tricycle networks that reach almost every nook and cranny of the town, the roads are relatively bump-free and not fraught with traffic. Rides can be had for as low as N30.

Over the years, I have come to embrace the energy of Lagos, even if I’ll never get used to the traffic and mad driving. And there’s enough people in Nigeria’s economic capital that are willing to give their money to online ride-hailing services to avoid both. Uber and Taxify obviously make sense in Lagos. But when I first noticed that ride-hailing services were springing up in the coal city, my hometown, I had a bit of trouble wrapping my head round it.

Ride-hailing services typically target big cities. DiDi, the Chinese ride-sharing giant which forced Uber to capitulate in China, is currently available in over 400 Chinese cities and is also present in Japan, Australia, and Brazil. Uber, the industry’s pioneer, has planted its flag in 785 metropolitan areas across the globe. Estonian ride-hailing service Taxify, is present in 50 cities in Africa, Europe, Australia, North America and the Middle East. Large populations with relatively high spending power, and in many cases strained transportation systems, make these markets perfect for ride-hailing services.

Enugu doesn’t tick all these boxes.

In the early 90s, Enugu’s economy was heavily reliant on coal mining. By the end of the civil war in 1970 and the oil boom shortly after, coal mining had gradually given way to trading, subsistence farming in rural areas and civil service employment at both state and federal levels. At about 3.3 million people in 2006, with majority of its jobs concentrated in civil service and a still-growing private sector, the spending power and cost of living in Enugu are relatively low. Compare this with Lagos’ population of 20 million and its much stronger economy. In 2017, Lagos’ IGR stood at N333 billion, the sum of 30 states put together while Enugu’s stood at N22 billion, just 32% of its federal allocation. While its population is relatively substantial (Taxify considers entry into locations with 1 million or more residents), their spending power is still debatable.

Enugu ranks 54th out of 169 on Fraym’s Index of Urban Markets in Africa.

One of the new services in Enugu, RideOn, launched just seven months ago. Oma, another ride-hailing service, and a word from the greeting je nke ọma (go well), appears to have launched sometime late last year (around September). Oma is one of seven startups incubated in Binary Hills, a tech hub in Enugu that launched in June, 2018.

I reached out to Oma to see if they would explain the economic thesis that informed their venture, but their representative wouldn’t say much. Something about not wanting to disclose details of their operations so early on in the sector. RideOn’s Operations Manager, Nwabueze Iwuchukwu, was more forthcoming and said that part of the attraction is that Enugu is evolving from a civil service state. The Akanu Ibiam Airport which was elevated to international status in 2011, has the potential to draw a more diverse cadre of visitors to the state when fully optimised for international flights. There is also a growing working-class youth population who are increasingly willing to spend on lifestyle-based services like online ride-hailing.

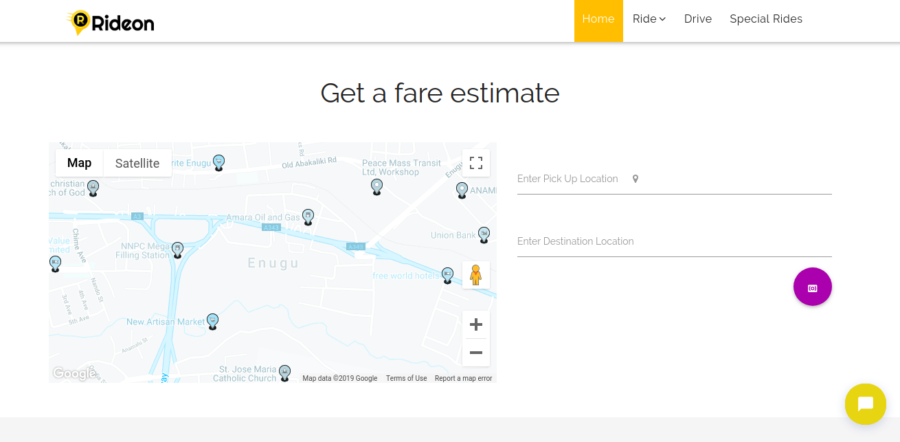

Both companies employ Uber-like pricing mechanics. The distance and time taken to cover a trip is used to calculate ride fares which Iwuchukwu says can compete with the prices one would pay to ride in the regular coal city cabs or tricycles. I attempted to replicate a journey I took across town during my last visit to Enugu on RideOn. The price estimate feature available on the website returned a fare of N1,215.675. A yellow cab to cover the same distance would have cost about N1,500 or more.

RideOn’s fare estimator allows you preview fares before booking a ride.

I reached out to a friend to confirm if she had used any of these services. She hadn’t but knew a few people who had. One of those people, Nnanna, tells me the service is convenient. The RideOn app indicates that drivers are about 5 to 10 minutes away on average, he says, and drivers usually arrive within this timeframe. I jokingly asked if the drivers offered sweets and asked a million and one questions about the temperature of the car like Uber drivers did when they first launched in Nigeria. They don’t, but are very professional. Will they miss their way to you due to their inability to read a map? Most likely not. Drivers do not necessarily need maps to find their way to you or to your destination considering how closely connected and small Enugu town is. Internet services from regular network providers work well enough to run your app and order a ride accurately on the map. He added that the fares were “very fair”.

But competitive pricing is hardly the only ingredient in the recipe for success in this business. There is still the question of the size of the addressable market. And Enugu’s transport system isn’t particularly strained. Another friend who lives in Enugu told me he hadn’t used any of these services, and wasn’t sure he would need to since the public transport situation works well enough.

RideOn says they now have 30 drivers and have conducted 2,000 rides within and outside the state since they started operations on May 31, 2018. I spoke with Augustine, one of RideOn’s drivers. Augustine began driving on the platform around October, 2018. It is his full time job now. On average, after commissions and operational costs are deducted, he makes around N35,000 a month. Average monthly salaries in Enugu can range from N50,000 – N80,000 depending on your line of work. For a single man or woman living in their family home, N35,000 might be enough to get by. With a family of three to take care of, Augustine is barely making enough. But the service is relatively new and he is confident about its future prospects.

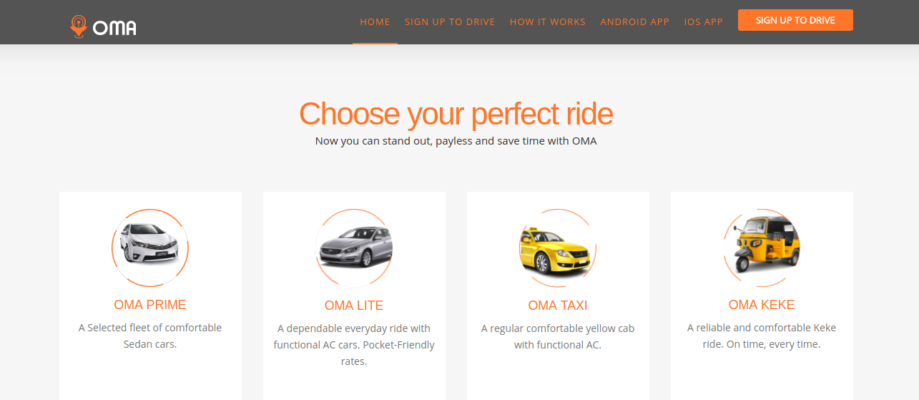

Will all of these ensure the longevity of these services in Enugu? I think so. Both startups have come up with a strong, diverse offering. Oma has included a tricycle hailing service on its platform while RideOn has incorporated a more robust array that includes out-of-state rides, school run services and a towing service. They also have a service that allows you rent a ride for a number of hours should you need to hop on and off a number of stops.

Oma also offers a tricycle hailing service to boost its service offering.

I lived the first 20 years of my life in Enugu, and I have observed a peculiar herd mentality with the business ventures there. People are quick to jump on a business trend, if it looks like the pioneers are thriving. Will there be more of these services springing up in the coal city? Maybe, and this will not be a bad thing entirely. A healthy, competitive business environment means that customers receive better value for their money and every company will continuously work to put its best foot forward. The only questions that the first movers, and any followers will eventually have to reckon with are if pie is big enough for everyone to share, and what they will do if Uber or Taxify eventually decide that they want in too.

What I do hope happens, is that when next I am in the coal city, I will be able to hail a cab from my mobile phone.