On December 10, 1948, at the United Nations General Assembly in Paris, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, was drafted. The 30-point document has become a guide for humanity to treat each other with dignity and as deserving of the best quality of life possible regardless of nationality, race, religious leanings, political ideologies, and every other dividing line that humanity has constructed for itself. Today, much of the context which set the premise for the formation of this declaration is still the same.

Threats to life, freedom, security of person, arbitrary arrests or exile are not only still infamously popular, but now, fueled by man-made advancements in science and technology, present in forms that did not exist in 1948. Nonetheless, nongovernmental organisations championing human rights in various parts of the globe are looking to technology and innovation to increase the scope and impact of their activities in areas where these NGOs are present.

Founded in 1961 by British lawyer Peter Benenson, global human rights organisation, Amnesty International employed the power and reach of the print media and letter writing in its earlier days to campaign and drum up support against human rights abuses. Also part of its modus operandi was producing research reports and legal documentation that supported its campaigns around the world. As it grew and began to take on more cases, driving campaigns through these traditional means became more cumbersome. Until the 1990s, when the invention of the web revolutionised the spread of information.

“External communication, documentation and transparency in procurement are very important areas where innovation has helped non-government organisations improve their impact,” says Saratu Abiola, who works with an international development organisation.

“You want to automate as much of your work as possible,” she stresses.

Technology adoption in Nigeria has been generally slow over the years. However, the adoption and penetration of social media have scaled significantly with the dip in smartphone prices and competitive data pricing. According to Statista.com reports, there were 29.3 million social media users in Nigeria in 2018 and this is projected to rise to 36.8 million in 2023. NGOs are now relying on these social communities online to spread their campaigns faster and wider.

“Amnesty International Nigeria has an urgent appeal mechanism that uses online petitions hosted on our website to raise advocacy on individuals at risk, human rights defenders and specific issues,” says Osai Ojigho, Director of Amnesty International Nigeria.

“We then promote the action using our social media accounts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram.”

Take the recent arrest of one of the conveners of the #ArewaMeToo movement in Nigeria. Or the disappearance of journalist, Jones Abiri, who was detained incommunicado by the Department of State Service for more than 2 years.

“Our petition received over 25,000 actions and eventually led to his release,” Ojigho says.

For Stand to End Rape (STER), a Nigerian initiative against sexual abuse and gender-based violence, social media has been instrumental in amplifying its messaging and capturing data, two key tools in the fight against sexual abuse.

“We started off on social media as just a hashtag, #StandToEndRape. As it grew, it became a platform and an instrument for victims to report abuse cases,” says Founder, Ayodeji Osowobi.

“In 2016, we partnered with Google Map UK to map hospitals, police stations and primary health care centers in Lagos State,” Osowobi says.

“What usually happens is that most victims only know about a certain center and so if the site of a crime is a distance away, it’ll take longer to travel all the way down.”

It is interesting to see how simple technology like cloud-based storage, data management tools like Microsoft’s Excel, and social media are driving very critical campaigns that protect the basic rights of human beings around the globe.

According to Amnesty International Nigeria’s Director, the campaign activities of the organisation isn’t solely executed on social media as they are also looking at how mobile applications can be used impactfully to protect human rights.

“This is a new area for Amnesty,” says Ojigho.

“We are interested in apps that help protect human rights defenders (HRDs) so that they can carry out their work safely. Surveillance is a real threat that puts HRDs at risk. A reporting app for documenting abuses would be welcome. However, it would also need to protect the rights to privacy and provide options to share information anonymously.”

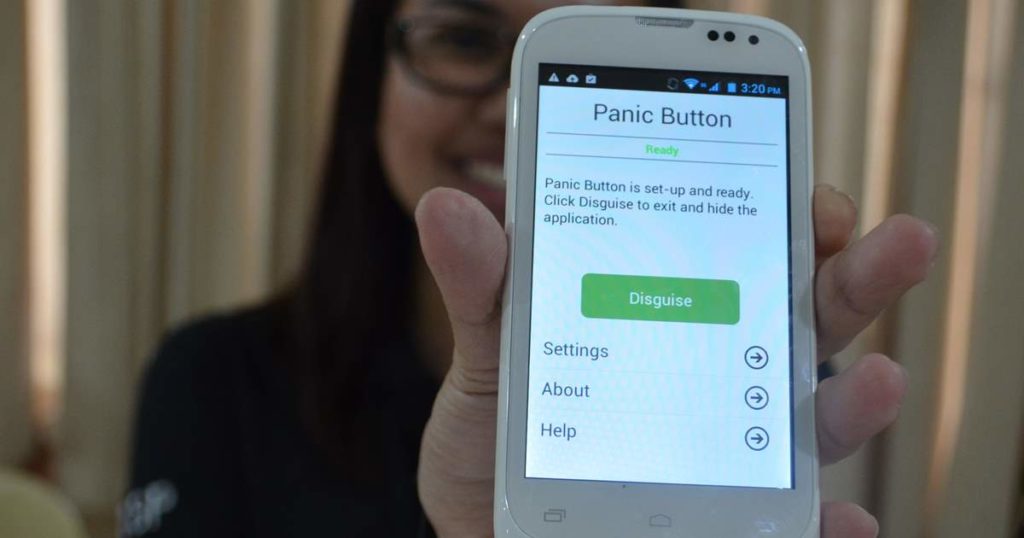

In 2014, Amnesty International launched a mobile app called Panic Button which they started building in 2012 with technology companies iilab, Frontline and The Engine Room. The SOS tool enabled activists especially those who receive threats in the course of their work, send alerts to three people in their network and update the recipients on their whereabouts every five minutes. In 2017, The Engine Room announced that the app was going to be retired largely due to a lack of funding for further development and technical issues that generated false alarms.

350 designers and developers worked to build Amnesty International’s Panic Button app which went on to be trialed by 120 HRDs from 17 countries in a six-month pilot.

As a furtherance of its drive to incorporate innovation and technology into its activities, Ojigho says Amnesty plans to keep exploring the ethical use of artificial intelligence and the delicate balance between this prospect and its ability to become a tool for abuse by way of its impact on the future of work, profiling of minority groups and discrimination.

But with a more determined drive towards advanced technology like robotics and artificial intelligence, Osowobi says it is important to never lose sight of the target audience.

“You can have the best innovation but if it doesn’t suit the needs of the target audience then it is just a project.”