How Shenzhen went from a sleepy fishing village to the Silicon Valley of Hardware, manufacturing 90% of the world’s electronics, is the stuff of legend. History points to policy reforms from the mid-70s to 80s embarked on by the then Prime Minister, Deng Xiaoping, which turned Shenzhen into the first of four special economic zones in China and quickly kicked off an era of rapid development.

Just around this time, as Shenzhen’s manufacturing and technology industries bloomed, Africa’s was dwindling after having risen remarkably from the late 60s during the post-independence era. While structural reforms sought to revive the sector in the 1990s, by 2006, the share of manufacturing in Africa’s GDP had declined to roughly 10%— the same as it had been in the mid-1960s.

Part of the reasons for this decline, particularly in Nigeria, came from policy reforms such as the structural adjustment programmes which a plethora of African countries would undergo between 1985 and 2000 that, contrary to what was obtainable in Shenzhen, began to stifle the industry and made it unprofitable for its players after a short stretch of revival. Nigeria’s for instance, which was introduced in 1986 under then Head of State, Ibrahim Babangida, was characterised by liberalised trade and low import tariffs that opened up an unfavourably competitive market for the local manufacturing industry.

“The level of manufacturing in Africa is generally low, but there are some pockets of growth in certain industries, such as auto manufacturing and assembly,” Nathan Hayes, Africa analyst at The Economist Intelligence Unit, told TechCabal.

Nonetheless, the sector is still largely inundated by International Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM), particularly from Asia in more recent times. Despite a stagnant manufacturing value added (MVA), China’s foreign direct investments in Africa has increased by nearly 200% in recent years, with a 106% increase in project numbers in 2016.

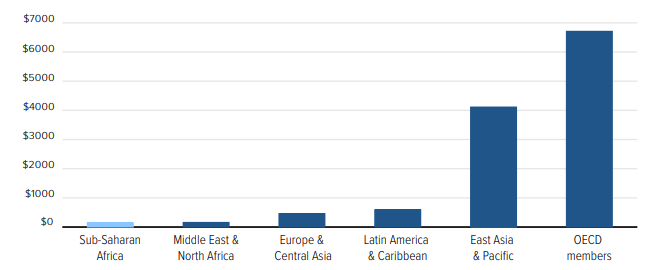

While intra-African trade increased by 6% between 2000 and 2014, trade in the manufacturing industry declined, from 18% in 2005 to about 15% between 2010 and 2015. Despite the increase in the last decade, intra-African trade remains negligible when put side by side trade volumes within other continents. Europe’s stands at 67%, North America at 48%, Asia, 58%, and Latin America, 20%. The challenges facing Africa’s industrialisation are many, from poor infrastructure to exorbitant tariffs and customs laws. The continent has seen an increase in pockets of trade agreements and blocs all of which has sought to break down these barriers to promote the freer exchange of goods and services across the continent’s borders. These include the East African Community (EAC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). In 2008, the EAC, COMESA and SADC sought to merge its trade blocs to establish the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA).

These trade agreements were recently consolidated in the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) which was signed in Kigali, Rwanda in 2018 by some 44 African Heads of State. Save Eritrea, the entire continent is now on board the AfCFTA ship and eager to see how this free trade area, now the largest in the world, will spur growth on the continent, especially for industries like manufacturing.

The Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index says human capital (talent and productivity), cost, supplier networks, and domestic demand are driving factors of growth in the manufacturing industry. The AfCFTA has now created a 1.2 billion people market many of which will constitute the 20% of global working age population (15-64 years) projected to come from Africa by 2050; and if its signatories can get beyond protectionist ideologies and implementation challenges, the agreement will make available a single market bloc with 97% of all tariff lines liberalised and over US$4 trillion in combined consumer and business spending.

“Once fully implemented, the AfCFTA will facilitate increased trade flows, investments across supply chains, increased industrialisation levels, improved market access,” says Hayes.

According to Obi Ozor, Co-founder and CEO Kobo360, the agreement is ushering an era where African businesses can boldly explore new collaboration and growth opportunities that would previously have been difficult or impossible under current legislative roadblocks.

“However, it could take some years for the benefits to be realised. The time frame for tariff liberalisation under the AfCTFA is 5years (or 10 for ‘least-developed countries’),” adds Hayes.

Still, spurring the IT manufacturing industry will require more than the removal of tariffs, including improving weak infrastructure—electricity, road networks, congested ports—present in many parts of the continent and tackling logistical bottlenecks. Upfront capital investments required to kickstart industries on large scale is also of concern as is the availability of technical know-how.

China has remained at the forefront of driving the AfCFTA and since it is the go-to-market for ICT hardware for the continent, there is also the need to consider how Sino-African relationships in the hardware manufacturing sector will evolve under the agreement. If Chinese firms begin to set up shop in Africa taking advantage of available (and cheaper labour when compared to Asia) or reduced tariffs, what room will there be for indigenous organisations to thrive? Chinese investments will largely facilitate trade across the continent under the AfCFTA, Hayes said.

Nonetheless, the AfCFTA is a step in the right direction for manufacturers.

“Governments must lead the way, with a firm hand on the wheel and by setting policy that creates an enabling environment for market-based growth that creates jobs,” says Kingsley Moghalu, former deputy governor of the Nigerian Central Bank.