In February, *Lolu desperately needed a soft loan to tide him over till payday. He asked two of his friends, but it was one of those months everyone you know is broke and hanging on their financial fingertips for payday.

Almost out of options, he remembered that someone at work had mentioned he could get a loan without going to the bank. He did a quick Google search and found almost a dozen digital lenders.

Today, there are over twelve apps which promise loans to Nigerians with “zero documentation and collateral”.

Lolu is like a lot of Nigerians, facing rising costs of living and no easy access to credit facilities. With rising unemployment and poverty, more people turning to quick loan apps to meet needs, tide over till payday and fund impulse buys.

Access to credit has always been tricky in Nigeria. While credit scores are largely nonexistent, the bigger problem is this: there are no real consequences for failing to repay loans.

To show how risk-averse Nigeria’s traditional banks are, credit cards are rarely issued to individual account holders.

MSMEs face the same problems, with many banks choosing the risk-free business of buying Treasury Bills or lending to the big players.

The market for individual loans has always existed, but it has always been high risk.

When family and friends were unable to provide credit, people turned to money lenders who charged as much as 30% interest monthly. These money lenders also required a go-between who would also serve as a guarantor.

Despite these safety measures, the business of individual loans remains fraught with risk. Stories of people absconding with borrowed monies are all too commonplace.

Tech meets high risk

After a cursory analysis, Lolu settled for KwikMoney, which promised him a N20,000 loan without any form of security. On if he read the terms of the loan, he admits he didn’t, saying: “Who reads these things these days?”

The availability of lending options has evolved over the last few years, with the entrance of tech-enabled lenders. The new crop of tech-enabled lenders use a range of data-led approaches that often combine machine learning and risk assessment based on personal data.

It is difficult to chronicle the beginning of tech-based solutions to credit facilities. But, one of the earliest players was the SeedStars-backed company, QuickCheck.

Launched in July 2016, the company claims it disbursed 3,000 loans within a 6-month period.

Apps like PayLater (Carbon), Zedvance, Branch, PalmCredit, OKash have now joined the fray. If you ever doubted the powers of tech, imagine telling someone five years ago that getting a loan would be as easy as dialling a USSD code.

The unique proposition of these digital lenders is simple; if you want a loan, you can get one. No awkward questions, no collateral.

Guaranteeing repayments with cold, hard data

Operating in a society where there are no real consequences for refusing to repay one’s debts poses one question: How do these companies give out loans with no questions asked?

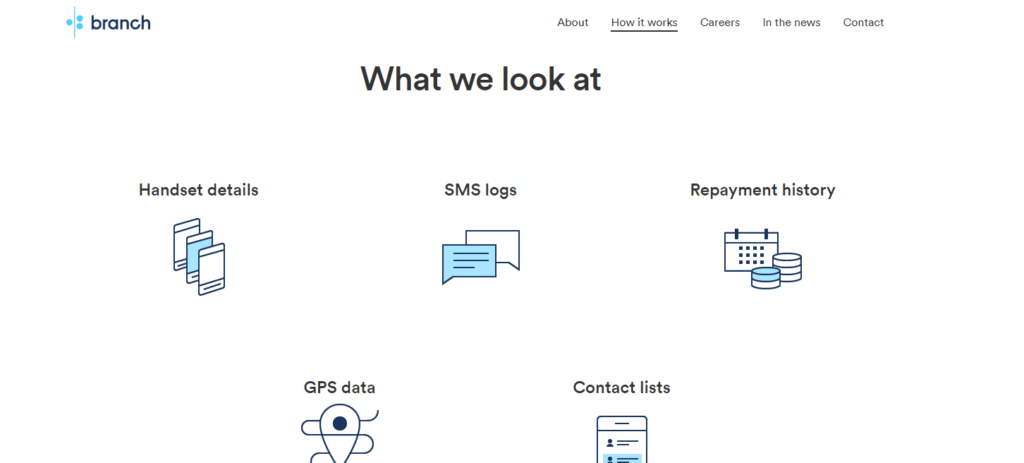

The answer is rather simple. Today, digital lenders make loan decisions with information that is more revealing and harder to game: personal data.

All digital lenders have algorithms that help them assess the credit risk of individuals. Call records are checked to find out frequently dialed contacts, SMS records are fair game.

If you know a lot of defaulters, then your chances of accessing a loan will take a hit.

Your GPS data is also up for grabs, as individuals with more predictable and stable routes are less likely to default.

Here is what is certain: each lender has a mix of algorithms and data points which it takes into account. These different data points then make up the secret sauce of its lending approach.

These are only a few metrics lenders are open to talking about. The exact determination of credit assessment will long remain trade secrets. An interesting point for is that although tech has the power to disrupt, societal values remain ingrained.

This is one of the reasons why, despite using machine learning to assess risk, default rates still remain high. The Nigerian attitude to debt is curious.

Nowhere is it more demonstrated than in the Federal government’s failure to recover thousands of loans disbursed to farmers under the Anchor Borrowers Scheme.

GTB’s QuickCredit, available to only GT account holders pegs loan amounts to a percentage of a salary earner’s average monthly income. It introduced an industry-low 1.75% interest rate.

Most digital lenders offer rates between 3%- 21% for loans under 60 days.

Digital lenders object to annualized interest rates, arguing that many of the loans they disburse are for short tenors.

What happens when people fail to pay anyway?

While a majority of the players within the digital lending space all favour apps, KwikMoney uses a low-fidelity model, ditching the app route for a simple USSD model.

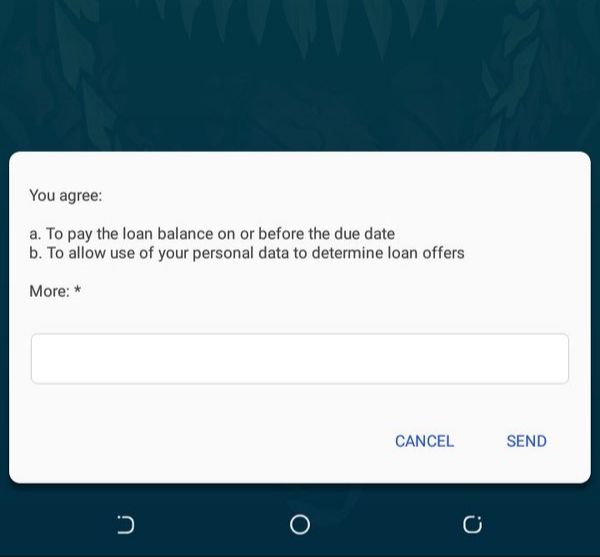

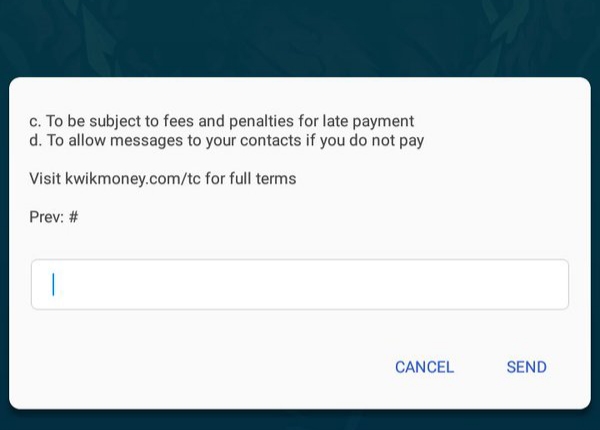

Like other players, they inform you that your personal data will determine loan offers. Yet, they go a step further, reaching out to your contacts when you default on payments.

Societal shaming as a means to debt collection is definitely not new. In Kenya, quite a few lenders use this method to shame defaulters into paying their loans.

It is easy to see how this potential loss of face can force the hand of a defaulter. Yet, unlike Kenya, Nigeria does not have a robust credit bureau, so when this trump card fails, what happens next?

Lenders will find some hope in one of the Central Bank’s newer regulations. On October 3, CBN granted Deposit Money Banks the approval to debit bank accounts belonging to loan defaulters across all banks in the country.

Privacy concerns

Does KwikMoney follow through on their threat to reach out to your contacts upon default?

We asked Uche, whose loan had a 2-week tenor and a 15% interest rate. One week after he defaulted on the loan, he received this reminder:

Ekechi Nwokah, the Managing Director of Mines, KwikMoney’s parent company, explains their approach:

“What we are doing is looking at your data and figuring out who is close to you, so that we can influence them to talk to you. If you see the messages, we don’t say: “this person has a loan”, that’s an invasion of privacy.

We just say we’re trying to reach them, please tell them to call us. It’s not coming from us, it’s coming from a bank, so they know, this is a serious thing.”

Ekechi Nwokah, the Managing Director of Mines

Nigeria Data Protection Regulation 2019

Data protection and regulation, still in its early stages, appear to still answer some privacy concerns.

With digital lenders having to deal with at least five regulatory agencies, the Nigerian Communications Commission gives the clearest indication of where we should look to.

The NCC refers matters of data protection to the National Information Technology Technology Development Agency (NITDA).

“The agency is statutorily mandated by the NITDA Act of 2007 develop regulations for electronic governance and monitor the use of electronic data interchange and other forms of electronic communication transactions as an alternative to paper-based methods in government, commerce, education, the private and public sectors, labour and other fields, where the use of electronic communication may improve the exchange of data and information.”

when assessing whether consent is freely given, utmost account shall be

2.3 (d)

taken of whether the performance of a contract, including the provision

of a service, is conditional on consent to the processing of Personal Data

that is not necessary (or excessive) for the performance of that contract;

The obvious question arising from the above section is: is collecting your phone contacts necessary for the process of giving loans?

For digital lenders, the answer is an unequivocal “yes”. Without traditional credit infrastructure, this data-led approach offers them a risk-assessment methodology. This in turn increases their capacity to offer loans to the “financially under-served”. They further argue that their products serve a real need, change lives and will serve as the beginning of proper credit histories for those who take these loans.

For consumers, where the possibility of quick credit exists, privacy is a seemingly small price to pay and even a close reading of the terms and conditions is a hard (unnecessary?) ask.

Yet, economic data shows that the bulk of small loans taken by the financially under-served are used to fund consumption, and the future of credit infrastructure is still uncertain. It remains to be seen if these small value loans, with their high interest rates and somewhat invasive data usage practices, are an expensive stopgap or a real ladder to financial inclusion for borrowers.