Nigerian fintechs move quick, banks move slowly; yet banks still win.

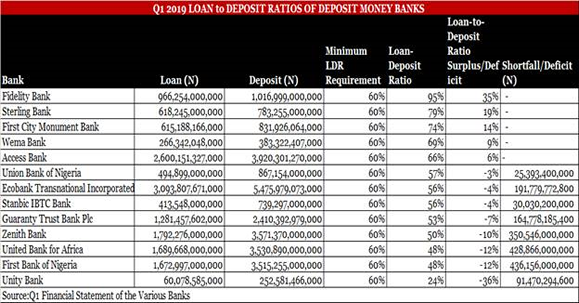

Nigerian banks don’t give out a lot of loans, especially to individuals and small businesses (retail lending). According to data from Proshare, big banks like Union Bank, First Bank, UBA and Zenith Bank provided less than 51% of their deposits as loans in the first quarter of 2019.

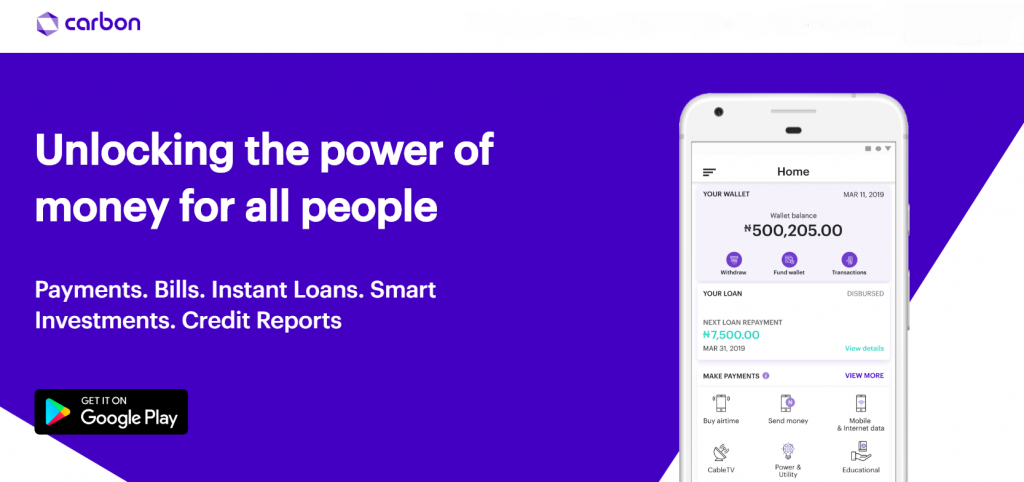

This reality is why fintech startups have emerged over the last couple of years. Growing at a period when the Nigerian market dipped into a recession, these startups have simplified the lending process, allowing people to secure loans within a few minutes.

Their rising number and innovative digital approaches have fueled speculation about what disruption could mean for banks.

Now, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) wants banks to lend more. This time it’s not just talking. It is compelling them, somewhat. But the new policy it has issued could set the stage for the first real tussle between banks and fintechs.

But hold up briefly; why do banks shy away from retail lending?

Why banks don’t do much retail lending

There are different answers to this.

“Retail lending [in Nigeria] is very terrible,” said a finance analyst at a top consultancy firm in Nigeria who requested anonymity. He explained that the underdeveloped nature of the retail space makes it very difficult for banks to provide loans to the mass market with a very high risk of defaults.

So banks are quite selective of the kind of people they give loans to. In the absence of credit ratings, banks target high-quality borrowers, “people with very solid places of employment,” the analyst said. They do this, he shared, because they can see your salary history and because it is easy to trace loan defaulters if they work in credible places.

“What banks are trying to avoid is the high cost of recovery,” the analyst said.

Agreeing with this, Abubakar Suleiman, Managing Director of Sterling Bank told TechCabal that there are three reasons why many banks don’t play in the retail market.

“First of all, if you [the bank] have not digitized the lending process, it is very expensive to lend manually to individuals because the workforce you need would have to be sizeable,” he said. Meanwhile, even while manual, the same workforce could be used to do large corporate lending at a cheaper cost per unit.

The second reason he said was data, which is obvious. “We [banks] just did not have authentic data, we just did not have identity [system] – and all of these are critical to lending,” he explained.

And third, Suleiman shared that the absence of bankruptcy laws for individuals makes it hard to recover retail loans. “So if somebody were to take a loan and not pay, the process of trying to recover the loan is so tedious,” he said.

But he explained that issues like credit rating, data integration and identity have been solved with the creation of the Credit Rating Bureau and the Bank Verification Number (BVN). Yet, the technological gap between fintech lending and bank lending remains.

“It is very hard to assess the risk of a retail lender,” said Julian Flosbach, General Manager Nigeria at FairMoney, an online lending platform. He adds that “traditional banks don’t have the technical capabilities to assess these risks outside their existing customer base – ergo, profitability from lending to large companies or the government/treasury bills is much higher for banks.”

“Rather than the banks lending to people, they are putting money into treasury bills because it is a convenient place to earn interest,” said the financial analyst.

So how does the CBN want to correct this?

What is the new CBN lending policy?

In the first half of 2019, the CBN began contemplating ways to get banks to lend more. With the banking regulator fighting hard to prop up the economy, it wants banks to complement its efforts by providing more credit that will stimulate the economy.

“For us to achieve growth those whose responsibility it is to provide credit must be seen to perform that responsibility,’’ CBN Governor Godwin Emefiele said in May.

By July, it issued a new policy. It ordered banks to increase their loan-to-deposit (LDR) ratio to a minimum of 60% by September 31, 2019. The LDR ratio is the total amount a bank has issued as loans from consumer deposits. Any bank that failed to comply will be forced to keep more cash with the CBN and earn no interest on them.

This may not sound like much of a penalty. But when the September deadline passed, the CBN forced erring banks to give up N499.1 billion ($1.4 billion).

It has since revised the LDR policy to 65% and extended the deadline to December 31. (It reviews the LDR policy quarterly.) Although it refunded the $1.4 billion, banks will be wary of the new deadline for LDR compliance. And this could increase competition in the retail lending market, a market fintechs want to dominate.

“If we don’t have that kind of thing as sanction coming from the central bank, what you will find is that most banks will not do it,” said Herbert Wigwe, CEO of Access Bank, Nigeria’s biggest bank by deposits.

How will banks meet the LDR target?

According to Suleiman, there are literally only two strategies banks can use to meet the LDR target: reject customer deposits or lend more.

“The implication is that banks will have to aggressively lend or aggressively reject deposit which they might not want to do,” said the financial analyst.

But the lending strategies many banks could adopt to meet the LDR target could lead to direct competition with fintechs.

Fintechs vs banks: Fight

Banks could refinance loans, Sterling Bank’s Managing Director, Suleiman alludes. With 79% of its deposits already given out as loans, Suleiman said his bank is no danger of the LDR penalty. But he said banks could try to attract loan customers from “other banks that are sleeping”.

“There will be competition in the market for who gets a higher amount of loans because everyone is trying to grow their loan books,” said the analyst.

But if banks lend more, it could affect the business of digital loans platforms for different reasons.

To begin with, banks already offer lower interest rates than digital lenders. Many fintechs offer loans with interests as high as 30%. But some banks like Guarantee Trust Bank (GTBank) offer loans as low as 21%.

If banks leverage this, it could cause fintechs to lose customers.

“I think that the first set of people that would migrate into borrowing from banks are the high-quality borrowers that are paying fintechs 5% per month,” Suleiman said.

“It provides this class of borrowers the same loans for less interest. If I were a high-quality borrower, I would migrate.”

But fintechs are betting that even with the push to lend more, banks will continue to focus on current customers. Flosbach, the General Manager for FairMoney admits that bank loans “would cost online lenders to lose some customers.” But he said banks are “very old-school and don’t focus on the average Nigerian.”

He predicts that “banks will try to lend more aggressively to corporates… [and] will enter the retail loan segment more and more.” “However, [they will] mainly focus on their existing customers, where they have visibility of their cash flows,” he added.

Could banks acquire fintechs?

Another way increased bank lending could have an impact on fintechs is how banks begin to leverage technology to reach new customers. “A lot of banks don’t have the capacity or the technology to do extreme retail,” said the financial analyst. Compared to banks, “we [fintechs] have an advantage and the technological advantage we have is huge,” said Flosbach.

Meanwhile, the next LDR deadline is in less than 10 weeks and subsequent ones could follow every three months. The timeline is too short for many banks to develop a market-ready consumer loan product.

They may have to acquire fintechs and co-opt their technologies for faster growth on the lending front.

“It is not impossible that banks will acquire fintechs,” Suleiman said, whose bank has built different digital platforms targeted at a host of consumers. He says acquisitions are possible “as long as they [banks] can transparently audit the logic of the fintech product to be sure it is something they are okay with.”

But he believes that regardless of the routes banks follow, all of them would have to build their own financial technology platforms. “Absolutely, they will all have to do it,” he said.

“It makes the cost of processing credit more viable for the borrower, removes the human element from the traditional system and improves the quality of user data banks can analyze.”

A few banks, like GTBank and Sterling, have already developed their own digital lending platforms. In 2018, GT Bank unveiled QuickCredit, a platform that offers instant loans with an interest rate of 1.75% monthly (21% annually).

In February 2018, Sterling Bank announced Specta, its own digital lending platform. Specta uses its own credit scoring engine to calculate the creditworthiness of borrowers and issues loans and accompanying interests based on that engine. It provides loans for tailored needs ranging from payday loans to rent and even wedding loans. Its loans typically carry interest of around 22% and 28%. Like regular lending platforms, Specta works for customers of any bank.

According to Suleiman, Specta has provided over N40 billion ($100 million) loans to customers across the country since it launched. “We are currently lending about N8 billion a month and we are projecting N10 billion per month,” he told me over the phone.

In another example, the Nigerian subsidiary of Standard Chartered has largely focused on corporate finance for over 20 years. But in September, it announced plans to increase retail banking from 6% to 15% of its revenue in the next two years. The company wants to also grow lending by 5%-10% by the end of 2019. “Retail is where we’re going to see exponential growth,” said Lamin Manjang, chief executive officer for Standard Chartered in Nigeria.

What this means is that banks could re-enter the lending market in different ways that could threaten online lenders.

Regardless though, many banks, for now, don’t have the technology that is required to be successful at retail lending. In addition, millions of people remain excluded from accessing financial services in Nigeria. According to Flosbach, “the amount of customers in Nigeria that is not (and never will be) served by traditional banks is huge.” His company, Fairmoney, and other digital lenders will be aiming to reach this group before banks can.