All things being equal, filmmaker Kenneth Gyang would have been about in Plateau, Jos, in the Middle Belt of Nigeria making a film on conflict resolution for an international non-governmental organisation.

“We had advanced discussions about production and then everything had to be put on hold,” Gyang tells TechCabal.

Even with the lockdown, which came into place in Nigeria on March 30 now lifted, there are no clear timelines as to when he can resume production.

Gyang’s plight is not singular.

Film sets are technically small communities of actors, producers, directors, gaffers, writers, makeup artists, costume designers, set designers, sound engineers and a host of other crew members whose roles directly make or mar a production.

On average, asides actors, crew members can number above 30 and in some instances 50 if you include assistants and extra hands depending on the magnitude of the project in question.

With distancing guidelines stating that people maintain at least a 2 metre distance from the next person, it is practically impossible to continue any kind of production at this time.

“I haven’t made any films in my head where the cast and crew total 20 which is what the guidelines say so it is nearly impossible to continue production,” Isioma Osagie, a Nollywood top producer, tells TechCabal.

Before lockdowns were announced in March for Lagos, FCT and Ogun states, over 700,000 cases had been recorded worldwide and countries were already enacting strict movement restrictions as one of the World Health Organisation’s immediate moves to curb the spread of the virus.

Keme Bedford, Nollywood producer for chart grossing films like Wedding Party, King of Boys and Love is War says a lot of filmmakers had raced to finish projects they had been working on as soon as it became clearer that the country might be moving into a lockdown. For productions that were unable to be completed, not much else has gone on since the lockdown was announced and lifted.

Taking film and television production remote

At a time when most activities have been forced online, some filmmakers and producers have attempted to leverage the internet and digital tools to continue production in spite of distance. For some, entire productions have been able to go on, like the makers of this film which was shot on mobile, directed via Zoom and released on video-sharing platform YouTube.

Freelance producer Lamide Akintobi tells TechCabal that one of her productions for a global media company, Five Answers With, has gone on in spite of the lockdown and even with the lockdown lifted, there is no hurry to resume physical productions. As a freelance producer, most of her work involves moving to set locations with a crew and interviewing individuals for a television production.

“There was a need for a format change,” she explains.

After drawing up a list of individuals for the production, Akintobi says she’s had to consider individuals who can self-tape, send them questions alongside clear directives and samples of the outcomes she desires.

“They were their own camera and their own crew.”

The first few episodes she’s produced for CNN Style feature Nigerian author Lola Shoneyin and social media influencer, Temi Otedola, both of whom can be said to have a hang of self-shooting visual content. And while a number of the other guests lined up are content producers who have fair knowledge and experience with self-producing, there are those for whom setting up a phone by themselves to record a high-quality video can be challenging.

“For those who are not so savvy, it’s a lot of talking people through, sending a lot of emails; I put together a guideline document,” Akintobi says, with minute details from desired phone settings, to ideal composition and audio instructions.

“I made sure to give them really detailed instructions in terms of recording.”

This format change has also meant that the content being produced has moved to digital streaming distribution platforms as against a usual television broadcast.

“We did a special episode that will be on TV next month but we will mention that it was produced during the lockdown so viewers can understand why it looks different and why it seems different,” Akintobi says.

Some productions have attempted to or are using tools like Zoom or WhatsApp for table reads or callbacks especially where auditions were carried out prior to the lockdown. But Osagie says even this isn’t ideal.

“A table read can happen on Zoom but it isn’t the sort of thing I would prefer because the chemistry of it might get lost via online interaction,” she tells TechCabal.

Administrative work, script writing, script development and shoot breakdowns have also continued in some form during this period remotely.

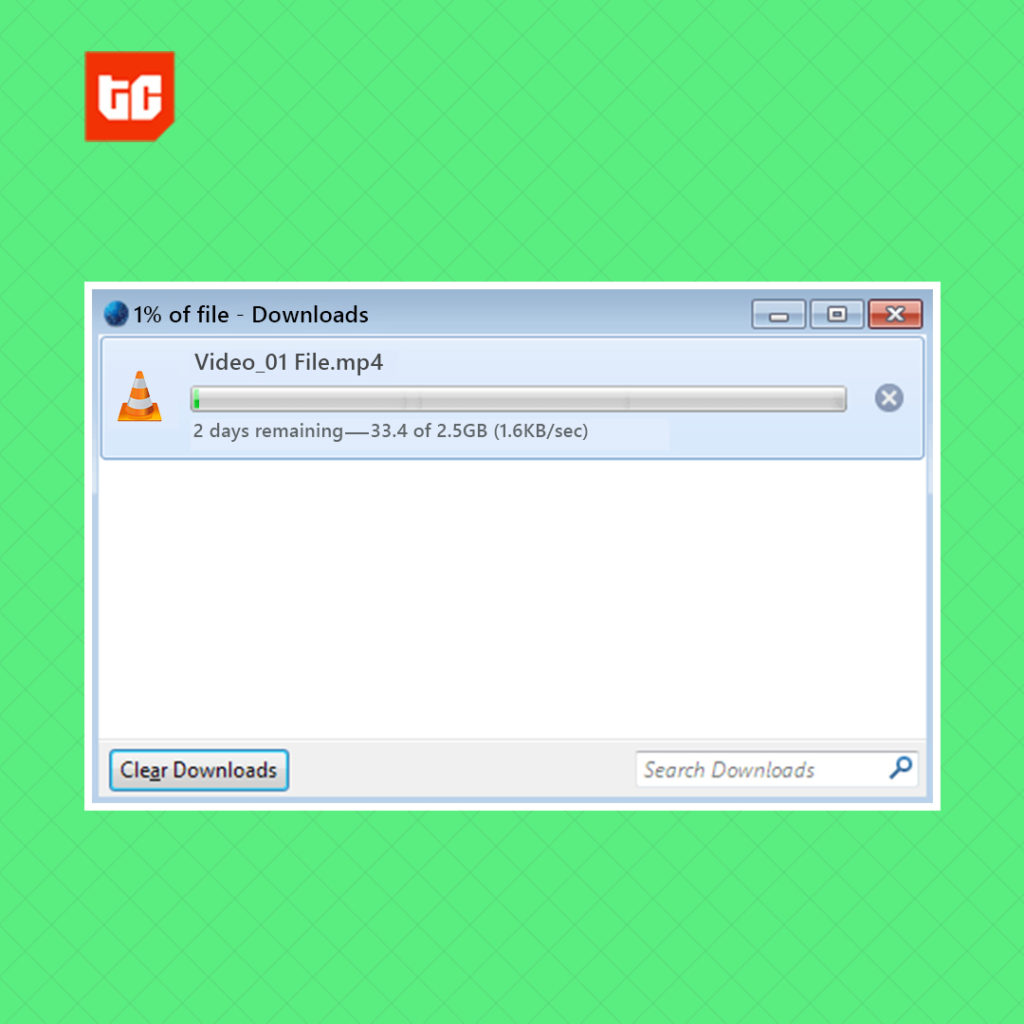

Naturally, there are challenges with this. Zoom’s hacking troubles during phone calls has been one but for Akintobi, transferring heavy footage across platforms like WeTransfer or Dropbox has been the biggest challenge with the remote productions.

“I’m getting screenshots of videos uploading and it is saying two days left.”

The Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) says ideally 1GB of data should not cost more than 2% of average income but at 8%, data costs in Africa are one of the highest globally.

There has been a lot of extensive reporting about how the coronavirus pandemic has unlocked a new level of digital adoption across a wide range of sectors globally. Court hearings are happening over Zoom, schools are going on on Google Classroom, even venture capital deals are being closed virtually.

But it is hard to see what difference it makes for the film and television industry.

Even with a one or two-man cast, what about the crew? The Lighthouse, a 2019 horror film starring Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe had more than 30 crew members on the production according to IMDb.

Now, what?

Now, no one seems to be hurrying back to set. For one, the guidelines on crowd sizes and safe distancing has not gone away. So the uncertainty remains.

“With the lockdown lifted, for now, because a lot of the freelance work I do is for international organisations, overall, they are trying to make sure everyone is safe,” says Akintobi.

“So even though the lockdown has been lifted, there’s still like, let’s wait and see how things progress before you carry a camera and go anywhere.”

According to Osagie, even when it will be possible to go back on set, there will be new realities to deal with and these conversations are currently ongoing, somewhat informally, in the industry.

“Most of these conversations involve getting to a point where we can test everybody and Nigeria is not at a point where tests are going to be dished out like that.”

Even if everyone is tested and comes out negative, the ability to segregate the cast and crew well enough and long enough also becomes critical to limit interaction with people outside this secluded community.

“Then you have to think about, how would you shoot a crowd scene, for instance. If you have a scene in the film that needs 500 people, what are you going to do?”

Gyang says he has been asked the same questions by the international NGO he’s set to work with on the film and his plan is to hire and utilise resources available in Plateau alone.

“The resolution I took is that I am not going to bring anyone from outside of Jos to join the set because the situation is not as bad here,” he tells TechCabal.

Out of 3,526 cases so far in Nigeria, Jos has only recorded 4. Officially.

For Akintobi, small factors like transporting crew members, the use of safety gear like masks, sanitisers, will be non negotiable. Small gear changes also, like replacing lapel mics that require proximity to set up with boom mics, will also be paramount.

“There’s no film that we shoot that should be more important than human life,” Osagie says.

Distribution and costs

What all of these mean is that the cost of production will definitely increase and filmmakers who have already embarked on projects before the lockdown may have a hard time recouping their funds when and if things return to normal.

“Let’s say you were going to transport 18 people from camp to set and you were going to use an 18-seater bus. Now you probably have to use a 30-seater so that no one has to sit next to each other,” Osagie explains.

“So the cost implications will increase.”

Distribution isn’t really something that is decided upon on a whim, Gyang explains when I ask if over-the-top (OTT) streaming platforms will become alternatives to reach audiences now that cinemas have been shut, an option Indian film producers are exploring to the displeasure of cinema distributors.

“I was discussing with a filmmaker who is in post-production now for a film they wanted to release around June/July. The problem is that, how are you even sure that it is going to be safe for people to go to the cinemas by then?” Gyang asks.

Monetary-wise, he explains, OTT streaming platforms may not necessarily yield any profits especially for productions where budgets have been drawn, marketing and profit margins estimated and signed off on. But there’s also the ‘way things are done’ and jumping a distribution stage isn’t the best scenario for your project.

Filmmakers generally resort to a consortium of distribution channels to make profits on their projects. OTT platforms acquire films in a number of ways from upfront payment to commissioning projects. Global streaming platform Netflix launched this year in Nigeria and acquires Nollywood films between a reported ₦2 million and ₦100 million but cinematic releases alone can generate as much as, if not more than this amount.

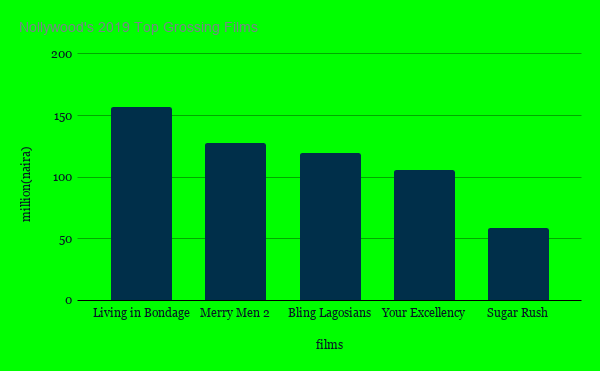

Last year, Living in Bondage grossed ₦157.3 million in cinemas and previous years have been even more profitable for cinematic distribution. The Wedding Party 2 which was released in 2017 has grossed more than half a billion naira (₦512 million).

“One of my films (Oloture) was supposed to be released this year but I don’t know when it will be released again,” Gyang says.

“With the money that has been spent making it, we can’t just divert it to a streaming platform because we want to release the film.”

While there are still filmmakers expressly targeting online streaming platforms with their content, it is not the go-to distribution route for a lot of filmmakers.

When the cinemas do open this year, if they will, there will naturally be a jostle for spots on movie schedules as filmmakers race to make up for lost time and recoup production costs at the very least.

“It’s just a bad year for filmmakers, to be honest,” says Gyang.