As I take my seat in this silver-coloured Toyota Corolla on Wednesday morning and settle into a conversation with its driver, I realise from a quick scan of the dashboard that it is not a new car.

Which means by August 20 – if the new Lagos e-hailing licensing regime takes off – it will likely not be on the road as an Uber or Bolt taxi.

The driver, Eze* is an energetic, streetwise man probably in his early 30s. Between our seats, there is an unsealed plastic bottle of coke, a loaf of bread and four balls of akara half the size of a day-old infant’s fist. It’s a breakfast of ₦300 (63 cents) to begin the day’s work.

It’s been three years since he became a Bolt driver but Eze still, according to him, has “nothing to show for it” and now longs for an exit. His short-term focus is to keep meeting up with the ₦25,000 ($53) he remits weekly to the car owner under their two-year hire purchase agreement.

So he would rather not dwell on the incoming taxi regime to avoid overburdening his mind. The new Lagos ‘Taxicab License’ requires Uber, Bolt, In-Driver and newcomers to pay one-time license fees of ₦10 million ($25,814) and an annual license renewal fee of ₦5 million ($12,907) for the first 1,000 taxis on their platforms.

A 10% cut of every fare (called a “service fee”) is also mandated.

“Even if Uber and Bolt pay these fees, it is you and I who will suffer,” Eze says, disguising the palpable concern in his voice with a wry smile.

Taxis are essential aspects of urban life across the globe. More so in Lagos given the poor state of public transportation.

Upon taxing such a commodity for which consumers are price-takers, it is expected that the company offering that commodity passes the tax on to those consumers. Price subsequently increases without significant decrease in quantity demanded.

How Uber and Bolt will respond

At the moment, Uber and Bolt are coy on what their response will be should further lobbying attempts fail to reverse the law.

But it is expected that they will increase the commissions they charge drivers per fare (Uber takes 25% while Bolt takes 20%) and that riders will bear the brunt of the new tax as rides will become more expensive.

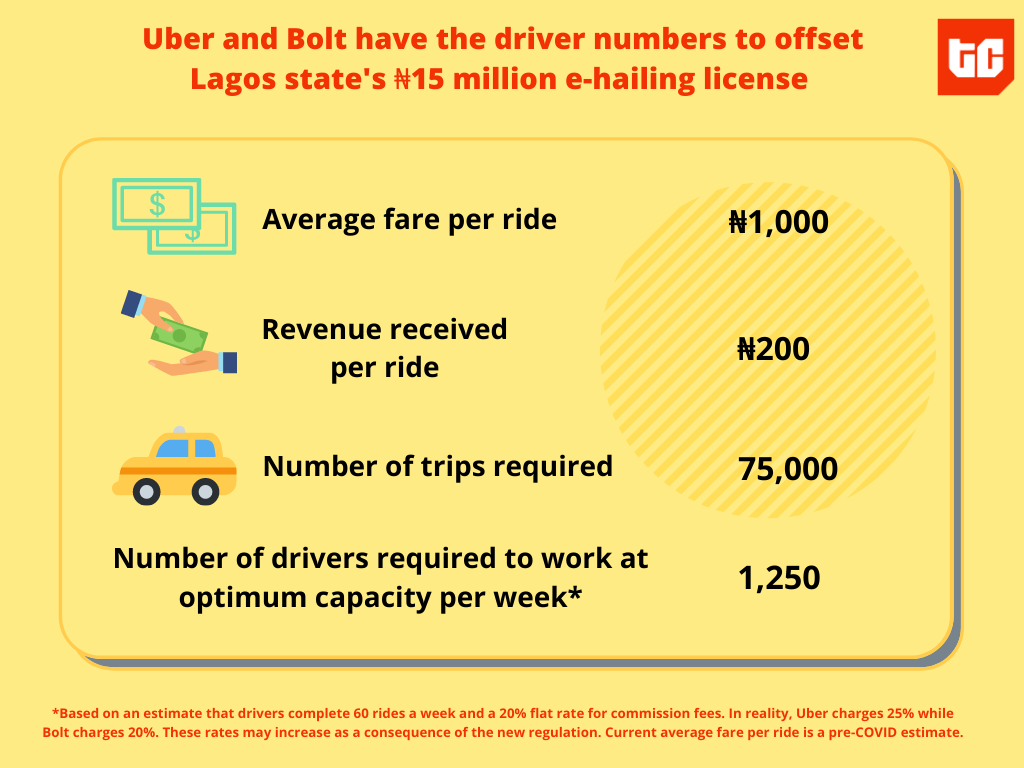

It is fair to assume the average trip on either platform in Lagos costs ₦1000 ($2.10), at least in the pre-COVID days. That means both companies make about ₦200 (42 cents) per ride, bringing the cost of their license plus renewal fees to the equivalent of 75,000 rides.

Drivers typically complete 30 hours of driving a week. At the rate of two trips per hour, that amounts to 60 rides per week for each driver.

With this back-of-the-envelope math, Uber and Bolt would need about 1,250 drivers working at full capacity per week to offset the license fees for the first 1,000 cars.

For the next 1,000 cars, the companies will need about 2,900 drivers working 60 hours per week to pay the ₦25 million ($64,535) one-time and ₦10 million ($25,814) annual renewal fees. There are about 9,000 or so Uber drivers in Nigeria with the majority in Lagos.

The calculation above is based on conservative estimates of how much fares cost at the moment and while the license fees are sizeable, it is not incredulous to say Uber and Bolt will make the best of this situation. License fees won’t be the sole reason they exit the Nigerian market as they face similar regulatory battles elsewhere.

Good regulation is necessary

In London, Uber lost its license last year for failing to fix safety concerns and Bolt faced legal action over minimum wage and workers’ rights in March this year.

Uber and Lyft are contemplating whether to shut down their services in California after being required to classify their drivers as employees.

There are legitimate reasons for regulating these companies wherever they operate. Any product or service that involves the interaction of two or more persons in public spaces requires public policy attention.

Nigeria’s internal security challenges demand there be certain features that make taxis recognisable to passengers and security operatives (Uber argues it is different from taxis based on its “pre-booking” feature).

Taxi rides are now one tap away but for many women, harassment and unwanted advances have become just as easy. It is concerning that these companies do some of their vehicle checks online without physically assessing the suitability for the service they promise.

Uber drivers need protection too from malicious actors posing as passengers, and from customers who proposition them.

Between December 2019 and early this year, road traffic officials were on a stop-and-search campaign requiring every Uber or Bolt driver to obtain a hackney permit and a special driver’s license issued by the Lagos State Drivers’ Institute (LASDRI).

Uber added both to their requirements in March, according to Business Insider SSA. But a push to mandate drivers to paint their cars has largely gone to the back burner.

Government’s unclear motives

But all of this buzz coincided with the launch of Ekocab, a rival app-based taxi company whose product mission is to incorporate the state’s traditional yellow taxis into the e-hailing system.

As TechCabal reported at the time, Ekocab was received as Lagos state’s attempt to compete in the industry. As such, many judge this impending taxi regime with the baggage of the state’s questionable attempts to clamp down on these companies since 2016.

The government’s sweeping claim that rogue Uber and Bolt drivers are to blame for “increased road crashes, kidnapping, robbery, pollution” is a screaming excuse for failing to address the actual vices long associated with the state’s yellow buses and their unruly unions.

Aluko* who drives his own car on Uber and Bolt believes the Lagos state government is “seeking to satisfy a certain big man who has a need for money.”

He is resigned to the increased commission that could be charged on his trips, but doesn’t see how the state will successfully implement the aspect of the law which requires that taxis should be brand new or within three years of manufacture.

His is a red-coloured Corolla manufactured by Toyota in 2003, just like Eze’s. As we drive through a busy main road in Ikeja, the Lagos state capital, Aluko challenges me to point to a car manufactured no later than 2017.

I observe that the state could go ahead to implement the law even if it sounds impossible dumb or impossible. He reluctantly agrees but suggests he may seek out a tinted glass permit and affix military insignia on his car to ward off snooping vehicle inspection officers.

As for Eze, he will continue to ensure his physical appearance behind the wheel doesn’t give him away as an obvious driver. That’s his hope for retaining his car on Bolt beyond August 20.

But he is under no illusions that the business – already significantly affected by weeks of inactivity due to COVID-19 – will be hampered by this new policy.

*Names changed to protect identity