Since the term was coined in 2016, femtech, a sub-sector in health technology dedicated to creating solutions that address female wellbeing continues to gain traction and attract VC funding globally. In Africa, however, the space is still very much in its budding phase. This segment is dedicated to telling stories of innovators, their solutions, the investors and challenges of the sector as it blooms in the continent.

A pop up appears on Derin’s phone on a Saturday evening. It’s Flo. She says hi and asks Derin if she feels her ovulation.

“Let’s talk about some interesting changes that are happening to your body during this time,” she says. Derin does not feel her ovulation nor has she noticed any interesting changes happening to her body. Flo says it will begin any day now, a mature egg leaving her ovary ready to be fertilized. Flo would know because over the past three years or more, Derin has been using the Flo app to track her menstrual cycle.

In the course of the last three years, Flo has allowed her keep track of her cycle, notifying her days before it begins and helping her track how her body changes during the cycle. The information she kept note of helped diagnose her for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a more severe form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and to consciously tackle it month after month.

Over time however, she began to worry about all the information she was sharing with Flo, about how much Flo knew and what else her data could be used for asides helping keep track of her body’s workings.

Flo, like many other period trackers, are among a class of early femtech products that sought to help women monitor and improve their reproductive health. Launched in 2015, Flo tracks menstruation, predicts menstrual cycles, alerts you to when you are most likely to become pregnant, and supports you through early motherhood and menopause. It is also keeping track of things like your body weight, water intake, exercise and sleep activities, monitoring the state of your mental health via your PMS symptoms and is able to analyse these data and present them in graphs or charts. Users are therefore inputting sensitive reproductive health records into the app daily or monthly from ovulation information to body weight, anxiety levels and frequency/kinds of sexual activity.

Over the years, Flo has created a Premium plan (you can access more content or take courses among other things) and added a personalised AI-powered chatbot so when Derin taps the pop-up on her phone, Aunt Flo (a colloquial term for periods) can chat with her briefly about ovulation and what changes she can expect to see in the coming days.

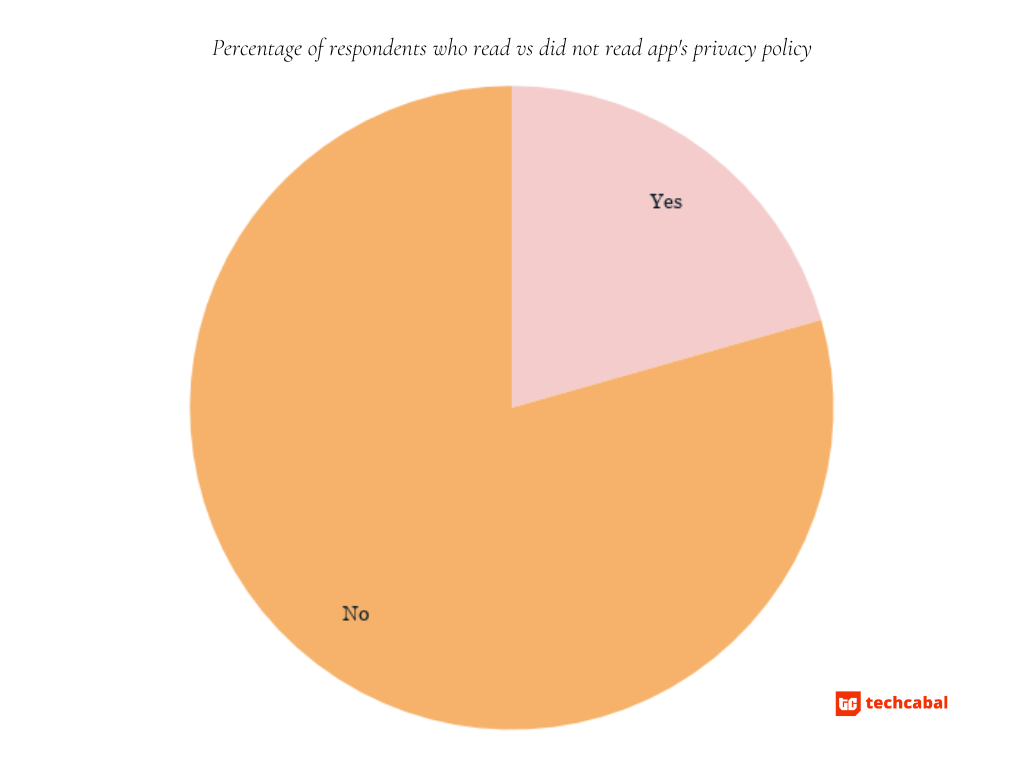

In a survey conducted among 35 young adult Nigerians aged 18-35, Flo was the choice period tracker in use with 31.4% of respondents saying that they used the app. However, more than 70% of respondents said they did not read the app’s privacy policy before creating an account. Only 23% of the respondents, like Derin, said they worry about where the data they feed their period tracking apps end up.

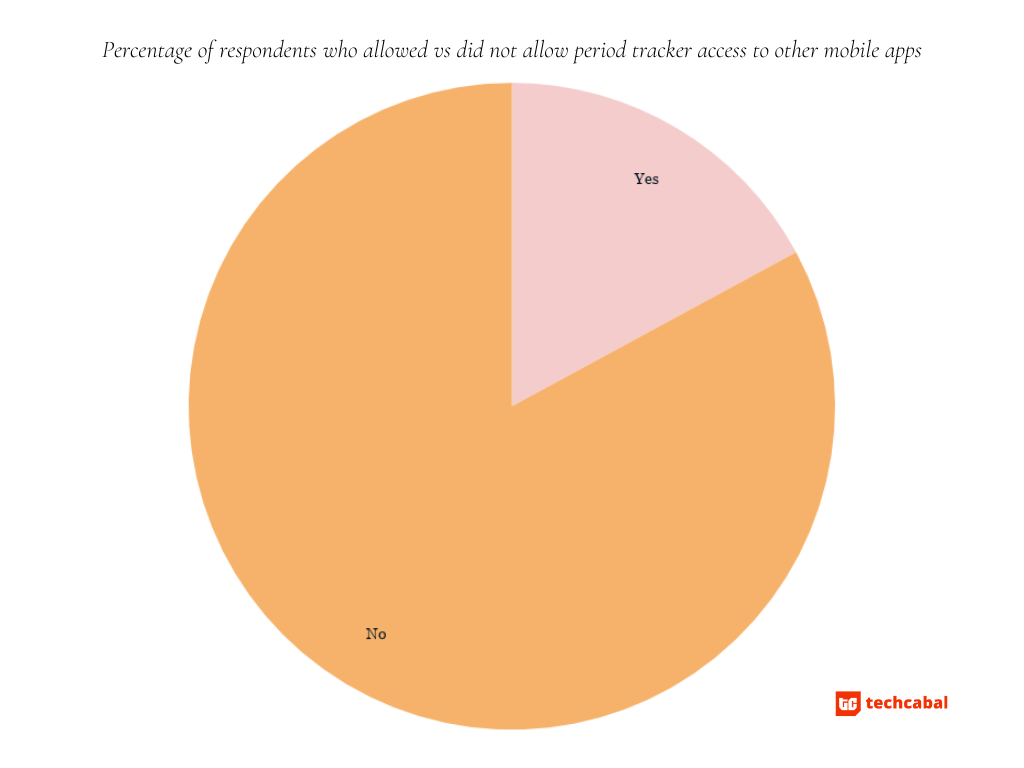

Oftentimes, period tracking apps request for and have access to other information asides what you input in the app sometimes, without your knowledge. And in the age of data mongering, this should concern anyone who regularly uses a period tracker.

Flo’s privacy policy makes it clear what data its 50+ million users voluntarily input and what it collects automatically which include device information, IP address, mobile network information, app usage and location among other things. To do this, cookies and other tracking technologies are often sent to your device to collect this information. While Flo says it does not disclose user information to third parties, “non-health Personal Data” is sometimes being shared with a mobile marketing platform called AppsFlyer which in turn shares some of these information with their integrated ad partners like Facebook and Google to market the app to new prospects like you and send you reminders when you’ve failed to open it for some time. These non-health data include information like your IP address, your age group and subscription status.

Now, privacy policies are boring documents. And there are too many of them to read these days as we continually welcome new digital consumer products into our lives. But it is important to understand how your private medical records are being used, whether cycle predictions are worth the trade off and what you can do to protect yourself.

How ‘safe’ are period trackers to use?

Consumer Reports, earlier this year, examined the most popular period tracking apps and their privacy policies. They checked for clarity, comprehensiveness, transparency, user control over their information and data security.

In addition to Flo, apps like Clue provide a fairly easy-to-read and clear privacy policy document within the app. The information contained tells users what is being collected voluntarily and automatically, how to request for changes to the information being collected, whom the data might be shared with and how the data is being used.

While a number of the apps do not directly share the information you input with third parties, the information they do collect can end up in the hands of one of the Big Five through marketing integrations with an organisation like AppsFlyer and for some apps, even very sensitive health and sexual records can be shared.

In a study of two period trackers, Maya and MIA Fem, Privacy International found that the apps were sharing detailed sexual and reproductive health information with Facebook and AppsFlyer sometimes even before a user consented to the privacy policy. A large portion of a user’s interaction with either app was recorded from when they opened it, to some of the very personal content logged in the diary feature of the app. Like Flo, these apps have short textual content addressing a variety of reproductive and health issues and for these two apps, they were able to relay what you had read to Facebook via a Facebook Ad Software Development Kit. My Period Tracker and Ovulation Calculator were other period trackers the findings revealed shared user data with Facebook.

Clue’s privacy policy states clearly what information it collects and to what purposes its sharing with third parties go. For instance, some information, stripped of any personal identifiers, may be shared with researchers working on female reproductive health. Also in line with Flo’s ad sharing, some information provided to Clue could be shared with ad companies to target new users. Ultimately, Clue stresses that any data being provided to a third party is solely to improve the app usage and never for the third party’s use.

“To be clear, these third party services are not permitted to use the data for any other purpose than to help us run Clue.”

A number of period tracking apps do not require login information to use the app each time like your banking app would, a practice Consumer Reports says is not well-meaning to users’ data but which might in fact, be beneficial. Without an account, your information is not stored on the app’s servers and so limits the extent to which it can be exploited.

My Calendar’s privacy policy is a brief document that states the app has no servers to store your private information, only allows cookies so it can improve app performance and navigation, and uses Facebook as ad providers.

In an age of data harvesting and leaks, digital footprints, algorithmic profiling and targeted ads, Derin is right to be concerned about the safety of her data largely because, oftentimes, one is not even aware to what extent this data is exploited to their career, health or social detriment.

Laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) and Nigeria Data Protection Regulation offer users some respite with the ability to modify what and how their data is used but can be limiting if an app’s origin does not bring it under either law.

Here’s what you can do

Regardless of how boring a privacy policy document is, it is important to read through it to understand what information is being collected willingly or unknowingly, how the information is being used, by whom and how you can opt out of what you consider an intrusive use of your data.

Perhaps it is best to lean towards apps that do not require account creation hence is incapable of storing your information in its servers.

Also be mindful of the information you leave an Aunt Flo and only provide what you deem is necessary to predict the information you want from your tracker.

Update your apps regularly as well so bugs that may expose your information to exploitative third parties can be rectified before they pose any harm.