In Nigeria, attempts at creating a National ID card dates back to 1986. After several decades and millions of dollars, the government is now looking to take the process digital

In Nigeria, getting any accepted means of identification can be difficult. A driver’s licence costs up to ₦10,450 ($27) while a Nigerian passport with 10-year validity is ₦70,000 ($181). While the pricing of these documents means many Nigerians cannot afford them, the process of getting them is still slow.

It is not unusual for public officials to demand bribes before you can get a passport or driver’s licence in good time.

The free alternatives to a national identification card are the voters card and the national identity card.

While the voters card is issued during election season, the national identity card is supposed to be issued all year long.

Yet, in five years, the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC) has had trouble issuing cards to millions of people who have registered. Innocent Chizaram, a Nigerian writer shared in this opinion piece that although he registered for an ID card in 2016, he is yet to receive it.

This kind of experience is why many Nigerians do not have any form of identification. In June 2020, the Director-General of the NIMC, Aliyu Aziz said only 38% of Nigerians have any form of identification.

According to Aziz: “over 100 million Nigerians have no identity (ID). These include the poorest and the most vulnerable groups, such as the marginalised – women and girls, the less-educated people, migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, stateless persons, people with disabilities and people living in rural and remote areas.”

Solving the Identification problem with the NIN

In 2007, the NIMC Act put the NIMC in charge of creating, managing, maintaining and operating a unified National Identity Database for Nigeria. The information the NIMC collects and stores includes biometric information, passport photographs and place of residence.

For each person who registers for the national identity card, a unique National Identity Number (NIN) is issued. This NIN is now tied to the Nigerian passport and there are plans to make it a requirement for students writing UTME examinations.

The NIMC is within its powers to do all of these. According to the NIMC Act, the registration and procurement of a National Identity Card is compulsory for all registrable persons in Nigeria. The registration is also free and has no age restrictions.

On paper, it sounds like the perfect solution to the problem. Yet, since 2007, less than 20% of Nigerians are registered on the National Identity database.

Many of the problems with the process can be traced to politics and a political process that has complicated what should be a non-issue.

A history of political problems surrounding NIMC

In 1998, Chams Limited, a Nigerian company won a $38.4 million contract to produce 52 million cards within four years. The project was off to a flying start, with Chams producing 1 million in 1999 while it waited for the Federal Government to buy some machines for the second stage of the contract.

While it waited, the government had other plans.

The Obasanjo administration handed over the contract to Sagem. In the end, Sagem was not able to produce all the cards required and the contract ended in a bribery scandal.

Chams on its part, went to court and won damages of $410,390. But the politics doesn’t end there: a back and forth between Chams and the NIMC meant that a concession agreement was not signed for years.

Yet, after it was signed, the contract would later be canceled in February 2015. Today, Chams is asking the Federal government to pay ₦44 billion ($113 million) in damages for lost revenue. Chams is also suing Mastercard for a breach of contract.

Nigeria’s national identity efforts have taken many turns and there is no immediate end in sight to the political problems plaguing the NIMC and the federal government. Now the government is hoping that digitising the process will lead to better outcomes.

Nigeria to dump plastic card in efforts to go digital

In August 2020, the government decided to move past the problems with the card process by focusing on digital cards.

According to the Minister of Communication and Digital Economy, Isa Patami, the priority for the government is now digital cards.

“We are no longer talking about cards, the world has gone digital, so that card is no more. Our priority now is digital ID, it will be attached to your database wherever you are.

“So if you can memorize it by heart, wherever you go that central database domiciled with NIMC will be able to provide the number and every one of your data will be provided. Now, our focus is no longer on producing cards, that card is only for record but what is important is the digital ID, and if you notice we have started using the digital ID on the international passport. Once you have the digital ID but not the card, we are 100 percent done with you.”

Anyone unfamiliar with Nigeria would have been surprised by the announcement. In any other country, the first step would be fixing the persistent institutional and operational issues with the NIMC.

There’s only so much technology can do and like some states in Nigeria have shown, everytime you pitch politics against technology, the winner is always politics. It’s not a bold prediction to say that digitising the process will not solve a systemic problem.

NIMC’s digital process falls flat on its face in opening weekend

On August 15, there were pressers that the NIMC had begun its online process for national identification cards.

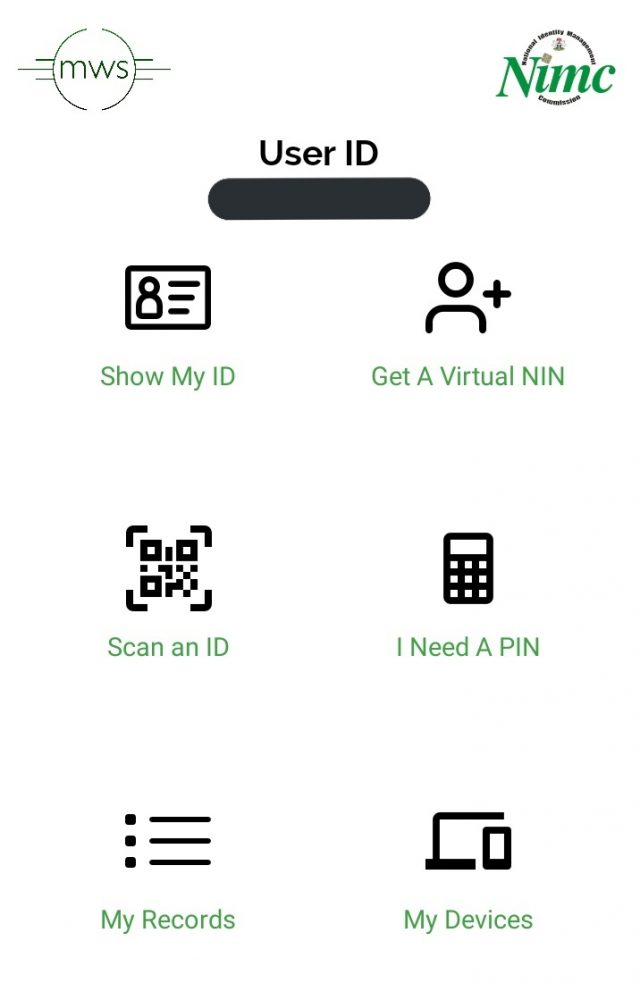

“First, you have to download the NIMC Mobile ID app, powered by its mobile services platform (MWS). Android users can visit the google play store to download and install the NIMC Mobile ID app. For iPhone users, they need to visit the app store to get the ios version of the app.”

-Technext

Despite some initial excitement over the app, the problems began quickly, with a few people pointing out that the app was leaking private information.

Two days after, the app was pulled from the Google and ioS Playstore. The NIMC said the app was a “novel innovation” which was not yet approved for public consumption. It’s a poor excuse by the NIMC and is yet another sign that it has not solved the operational problems it faces.

It is worth asking why an app not approved for public consumption had access to the entire NIMC database housing the data of millions of people. It raises several privacy issues and litigation has now begun.

A Civil Society Organisation (CSO), Law and Rights Awareness Initiative (LRAI), has now dragged the NIMC to court. According to this blogpost:

“NIMC also failed to file a data protection compliance audit report with the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) before uploading the personal data of Nigerians on “their insecure software application.”

“The suit also seeks an order of perpetual injunction against the NIMC to halt them from releasing more digital identity cards of the NIMC or any other platform prior to an external independent review of the safety and security of the NIMC’s app.”

While the court process will be interesting to keep an eye on, a system that cannot manage the process of printing cards will hardly be competent at managing the complexities that come with maintaining millions of digital identities.