Visual art is, well, visual. But when you stand in front of a piece of painting or sculpture, when you enter into an installation, there is more that your body does than view the work. There’s the spatial arrangement of the pieces to consider, the materials employed by the artist, the textures, the colours, the size of the canvases all made more real, more tangible by presence. But presence has been somewhat of a luxury for most of the year even in Nigeria and other parts of the continent where coronavirus lockdowns were brief and less stringent.

Art viewings around the world, as with many other activities, went online or began seeking out digital tools to aid their continuation in the absence of physical meetups. Galleries shut down, artists found new ways to grapple with creating in the midst of very uncertain times, and art promoters had to find ways to keep business going. Major art exhibitions like the Venice Biennale were postponed to next year and the doors to prominent museums like the Zeitz MOCAA in South Africa stayed closed for nearly seven months.

Nigerian galleries and independent curators found ways to navigate the period likewise. From hosting virtual reality-enabled exhibitions to artists’ talks on Zoom, the period opened up new windows that some think may become useful long term in the way art is shared and consumed.

Ugoma Adegoke, Founding Director/ Chief Curator, BLOOM Art

Founding Director and Chief Curator at BLOOM Art, Ugoma Adegoke says she “dragged herself kicking and screaming” in the direction of virtual art showing. The first virtual reality experience showing art pieces in the gallery’s space came in June, three months after the pandemic became full blown and lockdowns were enforced and lifted.

“I have very philosophical differences in opinion about how art should be shown just because of how I came into the arts and the role I feel art has to play in, sort of, cultural recalibration,” Adegoke tells me from her studio.

“I feel like the more serious it can be taken and the more apparent and obvious it is, the better.”

But three months without a viewing came at business costs and it was just important to find a way to bridge the distance and keep the work going regardless.

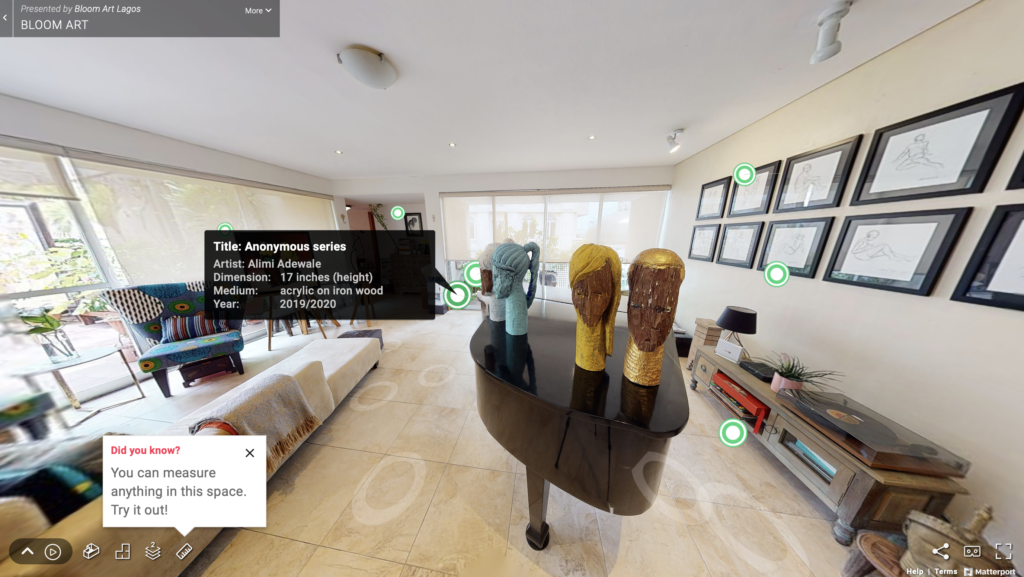

The augmented reality (AR) experience shows the in and outs of the BLOOM Art studio with paintings standing on easels, sitting on floors or hanging on walls accompanied by labels that pop up when you click on an individual piece.

In the months since June, a new version of the AR experience has been created with a rotating assembly of artists and their work. There’s been a July and September edition and a most recent version launched this month.

“I feel like we managed to still slap ourselves quickly enough because it was just obvious to me that it’s either we do something or we’re just going to completely die and there’ll be no more art,” she says.

To create the technology, Adegoke reached out to her closest network first: Kachi Joel Benson, producer and director of Daughters of Chibok; a VR film shown last year at the Light Camera Africa film festival which she founded, and Evoke Lagos’ Olugbile Holloway whom she had worked with to build a digital museum for First Bank of Nigeria.

The project would eventually go to Emmanuel Kuku (OA Visuals), a young man she had come in contact with through someone in her circle and who was able to create what she calls a moving panoramic view of the space. It was an expensive venture especially considering that there had not been any activity in the three months prior.

When considered in the long term however, she says it a worthwhile investment: a digital archive, a digital catalogue that helps whittle down in-house audiences to those who absolutely need to be there as well as a marketing tool.

While viewing the June installation, I did notice one striking piece of art, Memoir of Ancient Doors by Olumide Onadipe. It looked like another painting but with striking yellow patches that turned out to be made from plastic bags. From my mobile phone, I did not get the full textural experience of the work and I often wonder how much viewing art virtually can take away from the experience of being in the space physically and looking at the work.

“Even for someone who is trained and obsessed with art, of course, it takes away, I’d say, 80% of the experience,” says Adegoke, “Because art has very little to do with the physical material thing you’re seeing and so much to do with the space and the interaction between space, object, and you and the energies that come through in that moment.”

Sometimes, something as simple as rearranging the art pieces in a space can create a different kind of experience for a visitor.

“In my studio right now as I’m sitting talking to you, it’s as apparent with the power of moving the Tega Akpokona I’m looking at now from the easel on the left side of the room and placing it on the wall behind me.”

But one useful and lasting way Adegoke sees these virtual additions is in visual stimulation, in creating anticipation or suspense leading up to when the work can be seen in person. An interlude of some sort. A way for a viewer to begin conversations with the work before arriving at the gallery.

“We have decided that I will, of course, never try to argue that this can replace my physical ability and engagement to show art but I think I’ll keep it as a side tool.”

adéolúwa olúwajoba, Assistant Curator, Rele Gallery

For adéolúwa olúwajoba, navigating the pandemic has been on two fronts. First as a visual artist creating in the midst of global uncertainty and as an Assistant Curator at one of Nigeria’s most prominent galleries, Rele.

“Lockdown was getting on my nerves,” olúwajoba says and being able to create and find institutions that were still able to show art during the worst of the period was very refreshing.

olúwajoba was part of a virtual exhibition by POLARTICS in May titled I Hope This Finds You Well where he showed pieces from two bodies of work; Politics of Shared Living and Portraits From Solitude.

“It’s been a good time for artists to sit down and think about their work without getting caught up in the hassles of everyday life.”

Rele’s earliest virtual exhibition was titled Sculpting the City and had been in the works before the lockdown ensued. The group exhibition centered on sculptors and installation artists creating in conversation with the textures and materiality of the city.

To create the virtual experience, the pieces were installed in the gallery and an AR artist came in to film and create a three-dimensional augmented reality film which viewers could see through the gallery’s website.

Compared to physical exhibitions, olúwajoba says viewership wasn’t at all great but he credits this to the newness of the format and the Nigerian art scene still being quite heavy on in-house exhibitions.

For its annual Young Contemporaries program, the gallery employed a simple webpage to exhibit the work of the artists at the end of their bootcamp in August. For another exhibition, SUB.LIME, olúwajoba says they considered making it both a virtual and in-house exhibition but eventually went on solely with a physical exhibition at the gallery space. Visitors however, had to schedule their visits beforehand and obey COVID-19 guidelines. Currently, Tonia Nneji’s You May Enter is now showing at the space and people can come in to see the work wearing masks, sanitising and social distancing.

“Unless the lockdown lasted for a very long time”, olúwajoba thinks a more permanent adoption of technology tools in the arts would’ve been a slow and gradual process if at all.

“I don’t think of it as a replacement actually but an alternative way of viewing art exhibitions.”

Whether virtual exhibitions take away from art appreciation is dependent on a number of factors he says. For one, there are certain art mediums that are better suited for the virtual world. Film installations for instance, or digital art.

Nonetheless, he agrees with Adegoke in saying that the spatial arrangement of art whether it is a film installation working in concert with still art, is also critical to how it is interpreted and the virtual world is still incapable of creating something close to that physical experience.

“Scale is also a problem with viewing art online,” olúwajoba says.

The size of a piece of work can connote a lot of meaning, aid its interpretation and it is often something that is lost when art pieces are converted into VR experiences so that one might not have the slightest clue about the scale of an art piece when seeing it through their computer or mobile phone screen.

Business-wise, because of how established Rele is, connecting with its network of collectors and art buyers has ensured that business hasn’t suffered as much. Not many galleries or curators have this luxury.

Chidera Muoka, Founder, House of Zeta

To celebrate World Photography Day on August 19, Chidera Muoka, founder, House of Zeta thought to put up a virtual photography exhibition. Titled A Moment in History, the virtual exhibition brought together works by photographers in fashion, documentary, editorial and more.

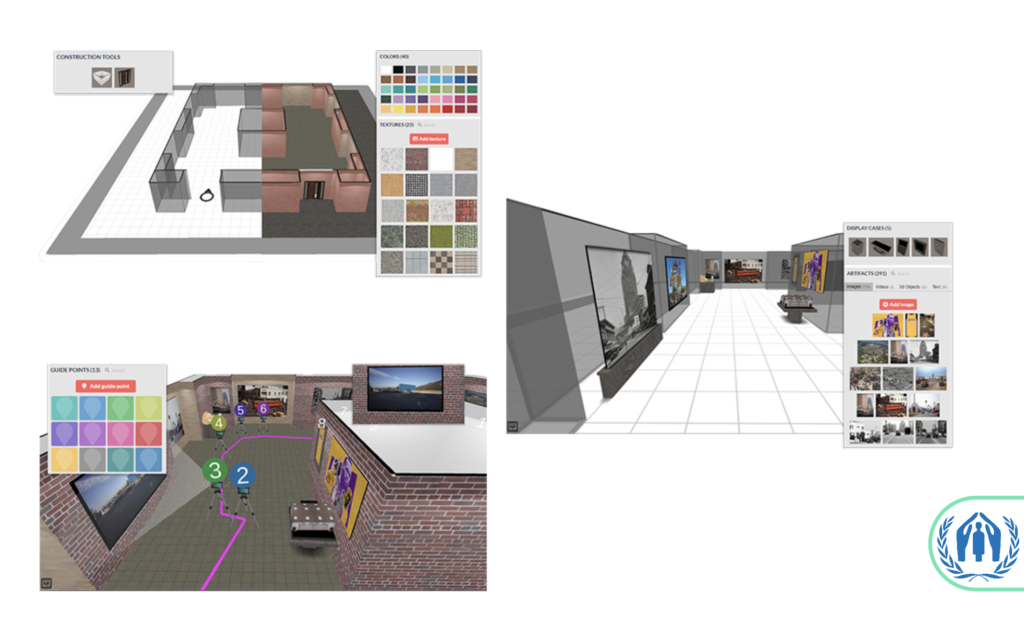

To create the experience, Muoka employed a digital exhibition platform called Artsteps. Launched by software development company Dataverse Ltd, the web-based platform allows its users to create virtual art galleries in 3D spaces using pre-installed or self-constructed templates.

Muoka says she learnt about the tool from a friend with experience in digital exhibitions and set up the exhibition by herself.

“By the time I got a hang of it, it did take a while and I’m quite the novice when it comes to tech,” Muoka explains.

While the exhibition was less of a hassle to set up and had provisions to ensure photos and artworks are licensed to be sold, the user experience wasn’t very satisfactory as not many were able to move through the virtual exhibition seamlessly. An in-app chat box where visitors asked questions about purchasing or the work themselves did not function quite effectively.

Still, about 1,000 people viewed the exhibition while it lasted.

For an independent curator with very little database of established consumers and art buyers, red dotting the pieces was difficult but the idea of the digital space impacting art viewing and buying significantly is one she considers far fetched.

“We are still getting used to the fact that there are even things like art exhibitions in this part of the world.”