What do you do when a company asks for your consent on its privacy policy?

If you’re like most people, you click on agree and move on. After all, who has time to read long and confusing legalese. The other option is to ignore or not accept (this option is rarely available) at the detriment of having pop-up reminders continually interrupt you.

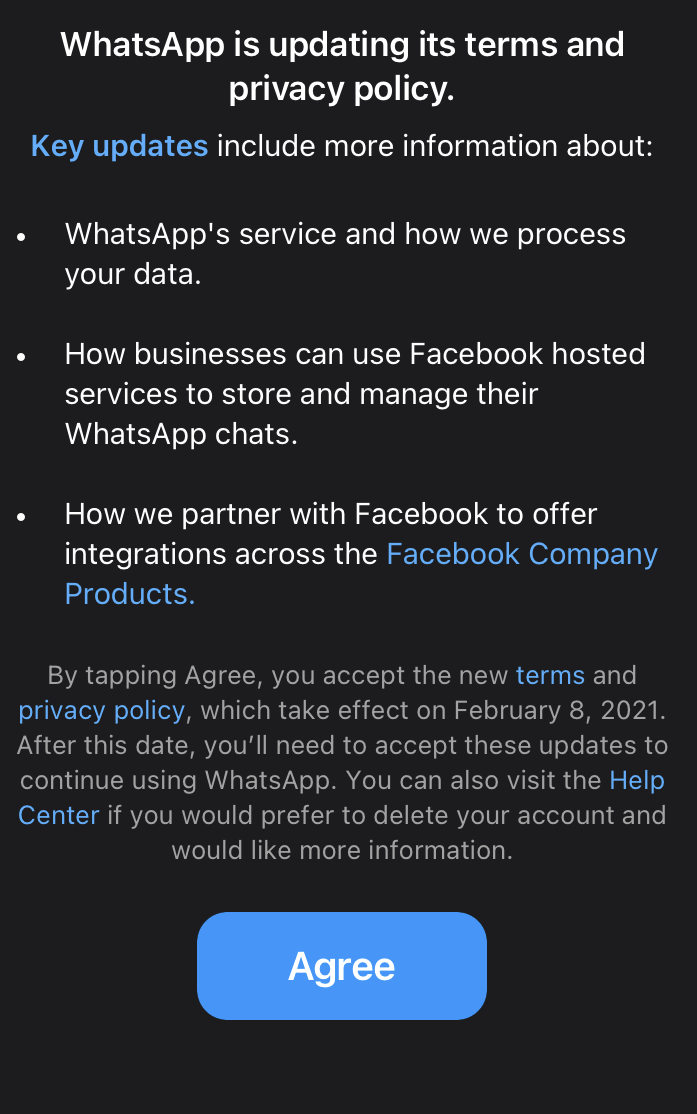

In the wake of Whatsapp’s recent privacy policy change, I’ve had to ask myself: do many Africans care about a privacy policy change? If there wasn’t an initial outcry by people who painstakingly read the new terms, would we have noticed any changes?

I spoke to WhatsApp users in Africa on whether they cared about this issue.

Justin*, an analyst from Nigeria, responded by saying he knows it’s the price he has to pay to use Whatsapp for free and he’s fine with it, as long as his data isn’t abused.

Amahle*, a South African media specialist, believes it’s not news that Whatsapp has been sharing our data with Facebook, she labels the public backlash as a reaction spurred by the media.

Abina*, a Ghanaian teacher, is uncomfortable with the data being shared, but she personally doesn’t care enough to stop using Whatsapp.

Why you should care about privacy

Even if you don’t care that companies make a buck off your data, it’s worth noting that personal data is used to make crucial decisions in our lives. It’s also used to affect our reputations, influence our decisions, and shape our behaviour.

Ben Wizner, of the American Civil Liberties Union, succinctly explains this by saying “For every single one of us, there is some pile of aggregated data that exists, the publication of which would cause us enormous harm and, in some cases, even professional and personal ruin. Every single one of us has a database of ruin.”

Ultimately, privacy is about respecting individuals. If a person has a reasonable desire to keep something private, it is disrespectful to ignore that without a compelling reason.

Protecting personal data in Africa

So far, 28 out of 53 African countries have adopted laws and regulations to protect personal data, and the number is slowly rising. An indicator that Africans’ general attitude towards privacy is still largely passive.

How much is your personal data worth?

In Africa, there is a big technology market. Data mined from Africans is being sold in the global market for a pretty penny but these same Africans are not afforded the basic data protection rights enjoyed in other parts of the world.

In 2018, American companies spent an estimated $19 billion obtaining and interpreting consumer data. This included anything from questions asked on Google to personal contact details.

This information is collected in various ways: sometimes the data is forked over knowingly, while in other scenarios, users might not understand they’re giving up anything at all.

In 2017, Daniel John, a Nigerian, sued Swedish company True Software Scandinavia AB, for listing and publishing his name and phone number without his consent. He was not a registered user of Truecaller (the company’s product) so their action was a direct violation of his privacy.

In many cases, it’s clear some information is being collected, but the specifics are hidden from view or buried in lengthy difficult-to-read agreements.

According to Financial Times’ personal data worth calculator, basic information such as age and gender can cost barely $1 per individual. But when a data collector can tell if you are a fitness buff, globetrotter, parent, or homeowner, the value of your data begins to climb.

Simply put, the more behavioural data you share, the more it is valuable to those who peddle it.

Despite all these glaring indicators, the general observation is that many Africans do not care much about a change in privacy policy because they don’t understand the importance of protecting their personal data or they’ve come to the sober realisation that social media platforms are not truly free and our data is the cost.

*Names changed… for privacy