My Life In Tech is putting human faces to some of the innovative startups, investments, and policy formations driving the technology sector across Africa.

It is noon when she joins our Google Meet call from her home in Amsterdam. On her side, the weather is 10 degrees but despite the cold, she tells me the skies are blue and the sun is out.

We spoke a week before she was to start her new role as Netflix’s Director of Payments for the Europe Middle East and Africa region.

Of the many laughs we had during the call, the most memorable came when I asked her what she would normally do to unwind after a long day at work.

“Netflix,” she said and we both cackled for what felt like a while.

There’ll be no escaping that big red N in the days to come.

But before Netflix, there was Uber, Etisalat, some DJing here, some scuba diving there.

Her name is Ebi Atawodi and this is her life in tech.

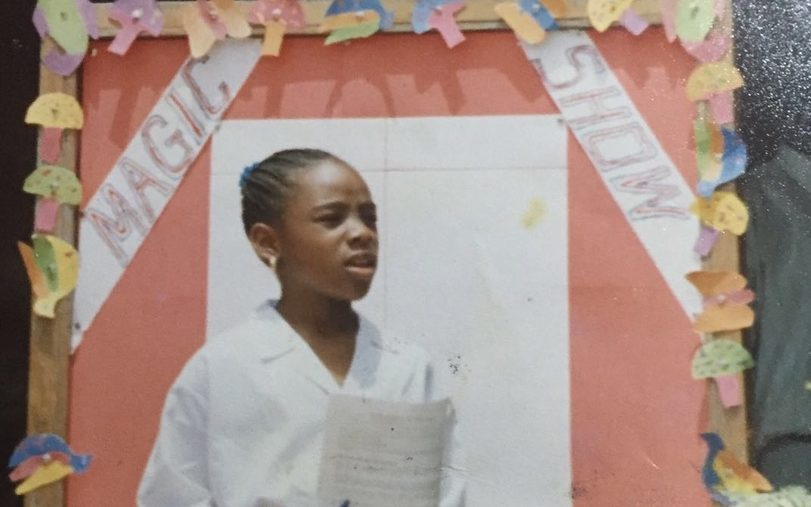

Give it up for the DJ. Full Stack Developer. Lifetime Scholar

If you visited Atawodi in her home today and it was evening, she would likely be at her piano playing music with a practised dexterity that tells you she does this often – and she does.

But if this meeting happened while she was an engineering student at Nottingham University, then you would have met a young Atawodi with her hands on wheels of steel, thrilling listeners with the thumping bass of house music.

DJing at the university’s radio station was something she did because she enjoyed music, but funding this enjoyment was no walk in the park.

“I love music. I worked hard as hell at two part-time jobs to make enough money to buy vinyl records for my turntables.”

While she studied at the university, Atawodi was already a full-stack developer and thanks to this, her university experience was different from that of her peers.

“[University] was not drudgery. I wasn’t going to the C programming class or the control systems class because I had to. I would go because I needed to understand what I’d be doing at work the next day.”

And her job as a developer was at a startup called Connect2Car founded by Kemgadi Nwachukwu.

Nwachukwu was an older family friend who, by sharing links to platforms like W3 Schools, helped Atawodi discover a whole new world of learning before she even got into the university.

“My mother was a book lover and we had books all over the house but it was the first time I knew that I could go on the internet and read and learn even more.”

Armed with her dial-up internet connection – slow as it was – Atawodi became unstoppable. From HTML to ActionScript, everything that could be learned was learned and the only limit she faced was her mother telling her to shut the computer down when it was time for bed.

With this hunger for knowledge at a young age, the stage seemed set for what will become one of Atawodi’s greatest strengths – her ability to learn and adapt.

From heading communications at Etisalat to heading payments at Uber, Atawodi has had to wear many hats and with each hat, she has had a system to help her settle into any role. Luckily for us, she had no reservations about sharing.

Joining a new team is daunting and for her, two things are important to get.

There’s the external knowledge; i.e, the things you learn before you resume your role.

“When I joined Uber [as General Manager] I remember I had a Google Doc of all the other general manager interviews in markets that were live, I watched all of them. I was taking note of what they were saying.”

Combined with this were hours of reading what people were complaining about and what the market wanted.

She would do the same when it was time to handle payments at Uber.

“I didn’t know anything about payments. I remember going online to google things like ‘payments 101’ and ‘payments for dummies’.”

After this comes the internal knowledge. The day arrives and now you have to start working in a company with an existing team and structure. For Atawodi, she draws inspiration from a book called “The First 90 days.”

The book insists that you know what stage the company is in; are they expanding, are they looking for investors, etc. and what comes next is questioning and listening.

“I do a 360 where I just go listen. I ask the relevant stakeholders what they do and what keeps them up at night. And then I ask them what they would focus on in the first 90 days if they were me.”

Atawodi emphasises that the journey to gaining knowledge begins with admitting that you do not have it.

“It’s okay to not know.”

“How about we stick to services?”

Ebi Atawodi was born in Lagos, Nigeria but thanks to her father’s work as a fighter pilot in the Nigerian Air Force, she had to move around a lot. Some years were spent in Benue, Nigeria, some in the UK and some others in Pakistan. With each move she had to switch schools.

“I once did a count and in total, I think I moved 12 times”

But even with all this movement, Atawodi loved being home in Nigeria.

During our call we talked about what she liked to listen to and apart from Bjork and Icelandic music, she listens to a lot of Nigerian music as it helps her not miss home as much.

After working a few years at a digital agency in the UK and becoming a tech lead with an appreciation for design, Atawodi wanted a taste of the business side of things; a chance to influence decisions as someone who knows what it is like to design, code and implement a solution.

She decided to create her own table and sit at it. This table would be her own business – the Apple Store in Abuja.

Today Atawodi tells me she is careful about how she hires people because of the events that led to the failure of that business.

After rigging a system by herself to detect foot traffic into her store, Atawodi found that she couldn’t understand why so many people were coming into the store and buying nothing at all.

To get to the root of the issue, she asked her friends to try buying items in the store and share their experience.

It turned out her employees had been selling Apple products that were not part of the Apple Store’s stock; hence losing Atawodi a lot of money.

The year was 2008 and when it was raining, it was pouring. The year also brought the global financial crisis and with that, the value of the naira plummeted and it became hard to justify running a business that involved buying and selling hardware.

“After that, I said, ‘you know what, I’m going to do a service business’. No more equipment.”

Despite her disappointment, Atawodi took another stab at entrepreneurship and set up her own digital agency which garnered a few high profile clients but it was not long before the CEO of Etisalat, a fairly new mobile network at the time, offered her a job as head of corporate communications and sponsorships.

Things to thank Ebi Atawodi for

Atawodi joined Etisalat in 2012 where she began to push for more partnerships that saw Etisalat’s brand grow by partnering with the arts and showcasing them.

Her love for literature, art, and music would come to play with a few key programs she introduced.

First, there was the Etisalat Prize for Literature. Instituted in 2013, it soon became a sought after prize for many African authors. This initiative also gave rise to the Etisalat Prize for Flash Fiction.

Second, Etisalat – through the Etisalat Photography Competition – became a major sponsor for the annual Lagos Photo Festival – an event that brought photographers from around the world to the city of Lagos for days of discussions, exhibitions and parties. A true cultural exchange.

The third was a service called Cloudnine that allowed people to stream music on their devices.

“Good is not good enough”

Atawodi abhors the idea that good is good enough. She is constantly pushing for better.

When there were doubts about her ideas for changing the way people pay for Uber across the globe, she simply let them know that she was there to show them another way.

And when there was skepticism about partnering with the arts at Etisalat, she said, “just watch me work.”

A lot has been written about Netflix’s incredibly competitive culture but a look at her history with competing against her own self gives one the sense that Atawodi may have just found a home at Netflix.

She was four years old when she jumped into a pool and almost drowned. Her floater deflated while she was in the water and a man dressed in his full squash kit jumped in to rescue her.

“Water became this thing that I feared and respected. I had this love-hate relationship with water, but I had to challenge myself. I am my biggest competition.”

Today, Atawodi begins her day with some indoor rowing. She also sails, and quite excitingly, scuba dives.

After leaving Etisalat and needing a long break, she went diving in the Canary Islands and Indonesia in 2014.

The trip was a truly memorable one for her.

“And then money finished so…” When she says this, we laugh again.

In Nigeria, Uber was about to enter the market and Atawodi, back from her diving trip, was at a conference where she met a launcher from Uber. After talking to him she started to ask questions about their strategies and tried to find out what plans they had and advised based on what she had learnt working with Etisalat.

Right there he asked her if she would apply to be General Manager. At the time, she just wanted to advise startups and take time off from a 9-5. After two weeks of being convinced, she applied and the rest is history.

One other thing that should be on the list of things to thank Atawodi for: today Uber has an API that allows people to pay for their Uber trips with whatever means of payment they have; from mobile wallets to M-PESA.

The journey to this achievement began on the day she woke up to find that over 90% of payments on Uber in Lagos had failed. The only people who were still able to use the Uber app were people who had linked their international cards.

With her knowledge of the market, she was able to set up the partnership between Uber and Flutterwave that now allows Uber to receive payments from local cards.

After this feat, Atawodi was promoted to Head of Product, Payments and like she’d done many times before, she had to move, but this time to Amsterdam. This role is where she created the API with the Uber payments team.

Today, she is in charge of payments for one of Netflix’s largest regions. And while it is a market with its own peculiarities, it’s important to remember that time and again Ebi Atawodi has shown that all we have to do is just watch her work.