The idea that a bank can be wholly digital is unrelatable and unremarkable to most Africans for two reasons.

About 66% of African adults are not banked. Whenever they ask for an account over the counter, they are referred to the customer service contract staff who requests certain credentials the user may not have.

Secondly, cash remains king on the street, the ultimate anchor of trust for everyday microtransactions. “Around 95% of all transactions in Africa are in cash,” says Raghav Prasad, Mastercard’s president for the Sub-Saharan Africa division.

“Africa needs its banks more than ever,” McKinsey, the consulting firm, declares in a report that extols banks as “fundamental” to the continent’s post-COVID recovery. It preserves the assumption of superiority and dependence that places consumers at the mercy of these oh-so-necessary glasshouses.

Secure in this feeling, banks do what they have to do to signal interest in consumers. But in board meetings, CFOs continue to hedge the health of their bottom line to the patronage of high-net-worth individuals, multinational companies, and government treasury bills.

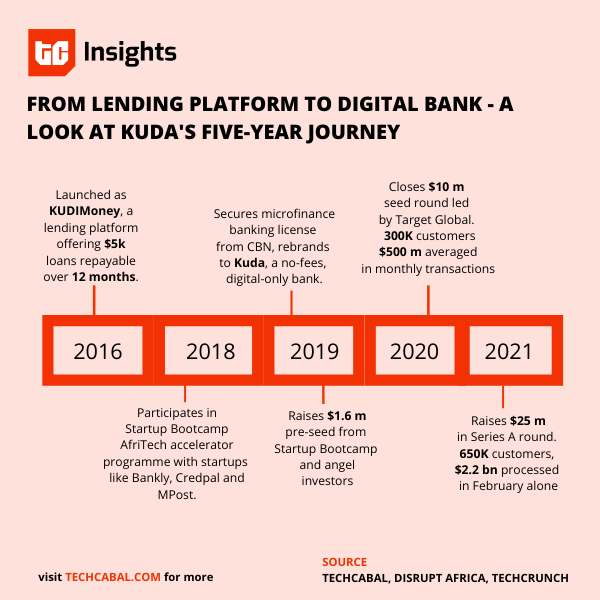

This delicate game of being a corporates-focused practice in consumer-facing garb could easily go on forever. Unless some institution, say the Nigerian fintech startup Kuda, does something about it.

Babs Ogundeyi, Kuda’s co-founder and CEO, says they want to bank every African on the planet. Ryan Laubscher, the COO, says they will do this by “blowing customers away” with unparalleled customer service.

The ambition will be fueled by a $25 million raise announced last week. But do we know how this money will be spent to achieve it? A truly consumer-focused, digital bank is not a novelty in 2021; there are models to emulate in Europe, the US and China. So where is Kuda looking for inspiration – if they are?

Monzo or Nubank?

Financial services delivery in Brazil is very similar to Africa, and Nigeria in particular. 60 million Brazilians are unbanked due to challenges like demand for paperwork and sparsely distributed branches that require long travels.

A stream of fintechs has risen to solve this problem. About 689 fintechs operate in Brazil, with 28% being payments companies. 3% are digital banks, and the most notable is Nubank.

Nubank is the largest fintech company in Latin America. It has 35 million customers in Brazil alone, with growing operations in Mexico, and Colombia.

Cristina Junqueira, a Nubank co-founder, told Bloomberg that 20% of the bank’s customers never had a credit card or a bank account before. They have helped customers save over $3 billion in fees since launching operations in 2013.

A year ago, Nubank launched Nu, its credit card, in Mexico where 36 million people are unbanked and only 10% of the population have credit cards. The physical card charges no annual fees and is integrated with Nubank’s mobile app, the base for its digital-only bank.

In Europe, British challengers Monzo, Revolut, and Starling, together with the German fintech N26, are popular in neo-banking conversations.

Starling has 2 million customers, Monzo is close to 5 million while Revolut has about 15 million customers with a presence in up to 10 countries. N26 celebrated reaching 7 million customers across 25 markets this January.

There are some differences in how neo-banks are used in European and emerging markets.

The typical European neobank customer uses their cards during travels abroad. Otherwise, those customers still keep their deposits in traditional banks like HSBC and Barclays.

This is a weakness for neobanks. During the height of the pandemic, despite the massive shift to online banking triggered by lockdowns, Monzo, Revolut and N26 experienced negative growth between January and May 2020.

On the other hand, Nubank rode the wave to grow by 16% because it is more of a spending account for users than a leisure account for travels (Starling also grew, thanks to its investment and retail lending venture). The Brazilian bank has built a data trove of up to 10,000 data points per customer, empowering it with unrivalled user knowledge for product and customer service delivery.

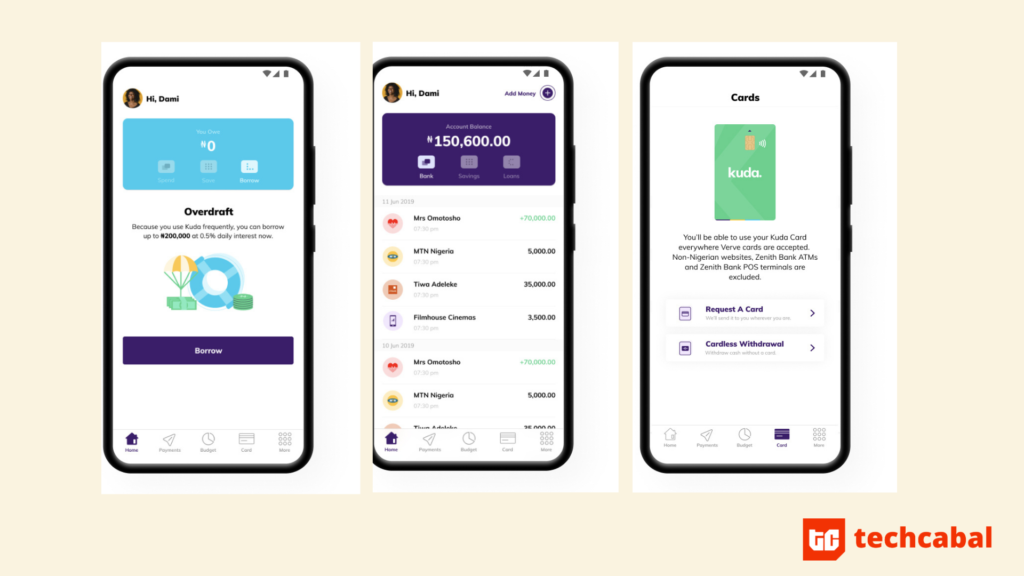

Nubank’s model – to be the user’s spending account for everyday needs – is what Kuda aspires to. Kuda doesn’t just want to be a fancy bank app on users’ phones. It wants to be as frequently used as social media apps.

A sticky banking app

Laubscher, the Nigeria-based startup’s COO, believes that by tailoring their services to the African environment, they can command user loyalty.

He says this will be the result of understanding the financial needs of users “extremely well” and creating data-driven products. With a firm foundation in data, Kuda would be able to offer unique credit to tens of millions of people, Laubscher says.

“There is plenty of margin for improvement on the product side,” he says, noting that their plan for unparalleled customer service delivery needs to be built around rethinking product delivery too.

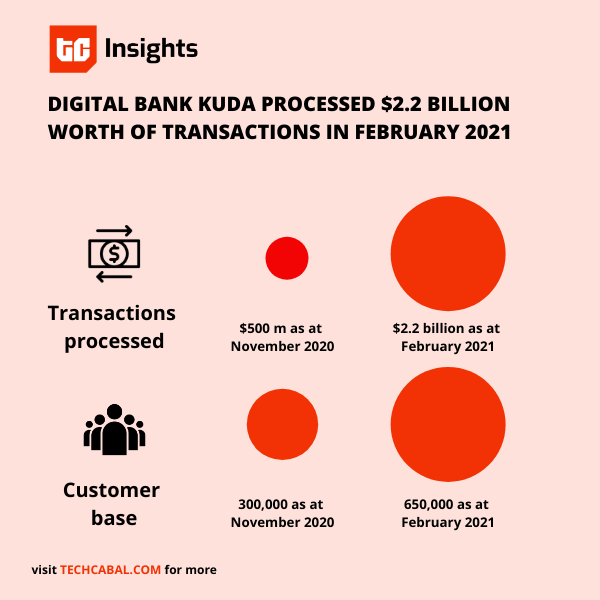

So far, transaction metrics appear to speak to what Kuda can achieve.

In February, the bank reported $2.2bn in transactions processed. This includes inflows and outflows, airtime purchases, and all other user transactions. When a user receives a $30 deposit and immediately makes a $30 transfer to another user, Kuda records the total transactions processed within that period as $60.

Such frequent transactions are good for the startup. It shows that the app is sticky i.e users have reason to open it often and perform some meaningful operations.

Kuda’s agenda in the medium-term is that as more people trust the system to function properly, more will let their deposits stay in the account for longer periods. The customer grows from using Kuda as a spending account to trusting it as a spending and salary account (and perhaps an investment account later?).

“We are making it easier for the customer to do what they need to do every day. Once people have tried us out and see it actually works, it builds trust,” Laubscher says.

Building trust in Africa

Given the sensitive nature of money and the dangers associated with online transactions, digital banking might need top-down regulation to inspire consumer adoption in Africa.

In Europe, digital banks have been afforded a favourable playground to experiment and grow, thanks to the Payment Services Directive (PSD2) standards developed to encourage open banking.

PSD2, which took effect in early 2018, emphasizes a technology-first approach that enables the rise of neobanks in Europe. It is a bold assurance to the consumer and investing public that digital banking is a movement that has come to stay.

Straightforward regulation has also helped Nubank in Brazil. In May 2020, the Central Bank of Brazil floated a framework for an open banking system; it kicked off officially on February 1 this year.

The Central Bank of Nigeria recently published an 18-page regulatory framework for open banking in Nigeria. For Laubscher, it shows “there’s now a supportive regulatory environment that is based on the customer and supports the customer.”

But regulation will be one side of the coin. Kuda and other African challengers will inspire more trust by getting more users to keep deposits with them.

“Trust is going to equal a deposit base. Without deposits, you can’t compete with the big banks in terms of credit provisions,” Laubscher says.

At the moment, Kuda is competing with and being complimented by its rival big banks in Nigeria.

Kuda requires users to sign up with a bank verification number but doesn’t have the capacity to issue it to users. So a Kuda user must already own a bank account from a traditional bank.

Also, Kuda depends on existing traditional banks for users to make over-the-counter deposits into Kuda accounts and make ATM withdrawals. These are limitations that come with holding a microfinance bank license instead of a commercial bank license. It’s also why the fintech is called Kuda, not Kuda Bank.

In that case, Kuda is not Nubank, neither is it Monzo or N26. But they have a clear ambition that may not take long to reach, if the present momentum is built on.